The Military’s Expanding Frontier

By Ayesha Siddiqa | News & Politics | Published 14 years ago

Recently, an article by a US-based Pakistani expat noted how Pakistan — at perhaps one of the most critical junctures in the history of its relations with the US and other parts of the world — has only a junior minister to mind the Foreign Ministry. That observation resonated in many quarters. And thereafter the anti-government Jang media group decided to investigate the government’s reluctance to appoint a full-fledged foreign minister.

Recently, an article by a US-based Pakistani expat noted how Pakistan — at perhaps one of the most critical junctures in the history of its relations with the US and other parts of the world — has only a junior minister to mind the Foreign Ministry. That observation resonated in many quarters. And thereafter the anti-government Jang media group decided to investigate the government’s reluctance to appoint a full-fledged foreign minister.

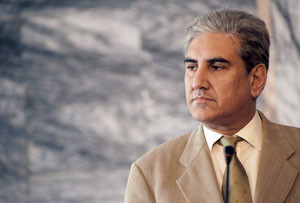

Notwithstanding the government’s general inefficiency, perhaps it has not appointed a foreign minister because it does not want to take responsibility for a subject that it is denied the right to administer and control. For too long it has been tacitly acknowledged that the Foreign Ministry has not been allowed to dictate or implement foreign policy. That has fallen largely under the purview of GHQ Rawalpindi. And any attempts at independence have been swiftly quashed — as former Foreign Minister Shah Mehmood Qureshi learnt to his disadvantage when he decided to challenge his own government’s handling of the Raymond Davis issue. Conventional wisdom may suggest that Qureshi was divested of his portfolio because he had defied his party. But political observers contend it was in fact the GHQ and not the political government that he had challenged since it was the military’s headquarters and not the PPP government that had decided Davis’s fate.

The Qureshi case begs the question: can Pakistan’s foreign policy can ever really be independent of army diktat?

The GHQ’s control of the Foreign Office and foreign policy is nothing short of a stranglehold and is both tactical and strategic. Tactically, the army began penetrating the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA) through the disarmament division. More than a decade ago, a serving officer was posted to this particular wing under the avowed premise of ‘coordinating activities’ pertaining to nuclear, chemical and biological weapons and conventional conflict-related issues. And it is no secret that strategically, the military has long dominated foreign policy-making, especially in relation to key issues such as India, Afghanistan, and the US. Thus, while diplomats have dealt with the tactical aspects or day-to-day running of the ministry, macro-level policy has been decided elsewhere. And differences between the GHQ’s and MoFA’s perspective on numerous issues have invariably been decided in the former’s favour.

For instance, each of the three service headquarters had their own perception of relations with Russia after the break-up of the former Soviet Union. A popular view among senior military commanders was that following its dismemberment, Moscow would be only too willing to strike deals with Islamabad. This view was not shared by MoFA, but its concerns were not taken on board. The military toyed with the idea of procuring MiG 29 and Sukhoi SU-30 fighter aircraft from Russia and even entered negotiations for these purchases. Eventually, better sense prevailed and Pakistan did not purchase the planes.

That notwithstanding, the military’s unilateral approach, particularly in respect of weapons procurement, has often proved critical to the outcome of negotiations. A lack of consultation with MoFA in several instances when all three wings of the armed forces have been seeking to procure arms has cost the military and the government millions of dollars.

That notwithstanding, the military’s unilateral approach, particularly in respect of weapons procurement, has often proved critical to the outcome of negotiations. A lack of consultation with MoFA in several instances when all three wings of the armed forces have been seeking to procure arms has cost the military and the government millions of dollars.

One example of this pertains to the procurement of the Type-21 frigates from the UK. The procurement process was initiated at a time when relations between Pakistan and a number of western countries were getting tense. The navy could have acquired better frigates from other sources which would not have been affected by any embargo, but no one sought an opinion from the Foreign Office.

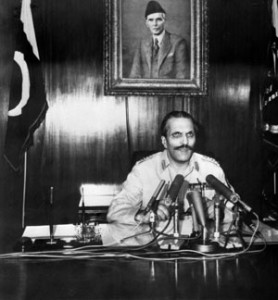

This, however is just one part of Pakistan’s skewed foreign relations policy. The more crucial issue is that of the military dominating the foreign policy agenda and tailoring it on the basis of its own defence considerations. We are reminded of the events during the signing of the Geneva Accords on Afghanistan in 1987. There was a sharp difference of opinion between Mohammad Khan Junejo’s political government and General Zia-ul-Haq’s GHQ. When the political government decided to go its own way and support the signing of the accords, it resulted in its abrupt dismissal. The reason offered for the dismissal was corruption, but it is no secret that Zia was unhappy with his prime minister who seemed, to the army chief, to be toeing America’s line rather than GHQ’s. Having learnt from the Junejo experience, the army thenceforth never let Afghanistan out of its sight or let civilian governments determine Af-Pak policy. It is part of our history as to how at that time Zia-ul-Haq used the ISI to engage with various Afghan warlords until a more ‘successful’ model for governance was found in the form of the Mullah Omar-led Taliban.

A similar situation pertains to relations with India. Calls for bettering relations with Pakistan’s traditional enemy have emanated from across the country. And various political governments, starting with Benazir Bhutto’s first government elected in 1988, have tried to improve relations with New Delhi. Rajiv Gandhi’s visit to Pakistan during Benazir Bhutto’s tenure and the Lahore Declaration during Nawaz Sharif’s government are a few examples of political administrations’ attempts to mend fences with their neighbour.

Even under General Musharraf there was talk of building trade relations between the two states, especially the two Punjabs. Several exchanges between the two sides followed, and the World Bank even published a report highlighting the financial and general resource benefits that might accrue to both sides of the Punjab with the initiation of trade relations. Later, the State Bank of Pakistan issued a report in which it recommended the benefits of opening trade with India. The conclusion was that such a development would attract Indian NRI money coming into India to Pakistan as well.

More recently, the Pakistan Business Council also recommended building and strengthening bilateral trade relations with India. However, nothing has come of these suggestions. Punjab-to-Punjab trade was like an open-and-shut-door case, primarily because the top commanders of the army did not approve of the idea. And it is widely surmised that today one of the major hurdles in improving ties with our neighbour is General Kayani’s alleged dislike for India. Those who have broached the issue of trade ties with India have been squarely informed that the general does not approve of direct trade with New Delhi. Being that as it may, there can be no argument with the fact that unless there is direct trade, Pakistan’s economy will not register any benefits. A lot of the machinery and chemicals required in the production of raw material for various Pakistani industries have to be purchased at a premium because they have to be bought and imported from other countries rather than the one next door.

How to handle India and Afghanistan are not the only two areas of contention between the government and GHQ. Pakistan has been unable to make any major strides in terms of policies, even with the Muslim World and ‘best friend’ China because of the constant interference by GHQ.

How to handle India and Afghanistan are not the only two areas of contention between the government and GHQ. Pakistan has been unable to make any major strides in terms of policies, even with the Muslim World and ‘best friend’ China because of the constant interference by GHQ.

Against this backdrop, it is unlikely that Pakistan will be able to emulate the Zulfikar Ali Bhutto era of an independent foreign policy any time soon. Bhutto had a vision that translated into foreign policy initiatives which linked Pakistan much more closely with the Muslim world than before.

As to what our diplomats and strategists like to call ‘Pakistan’s only set of strategic relations’ — i.e. our ties with China — this is far from the large or the real picture. We cannot call our links with China strategic; our people do not know each other. In fact, the Chinese have more information about India than Pakistan. Furthermore, even what might have been a truly viable relationship is often put to the test due to the military’s shenanigans. The constant traffic of jihadis into China from Pakistan has resulted in borders between the two countries being closed for varying lengths of time on several occasions in the past five years. And the dumping of Chinese goods in the Pakistani market, or the inability to negotiate with the Chinese on relatively more advantageous terms, is a direct fallout of Pakistan’s security discourse-dictated policy. We fear that if we were to question the Chinese, they may not sell us their military technology. This approach not only costs us financially, but it also deprives us of technological and business gains.

A good foreign minister leaves a deep mark of his/her personality on foreign policy. However, foreign ministers and their ministries, if fettered, cannot leave a mark. In Pakistan’s case, the GHQ and its ISI are the country’s Foreign Ministry and their influence has continued to grow since the early 1980s. In many ways, thus, who can blame the government for not appointing a foreign minister?

The writer is an independent social scientist and author of Military Inc. She tweets @iamthedrifter