Hostage to Political Players

By Amir Zia | News & Politics | Published 14 years ago

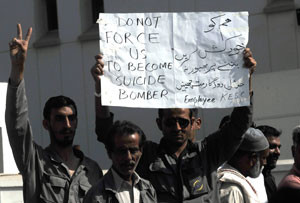

For several weeks, the Karachi Press Club (KPC) has been under siege. Hundreds of protesting workers from the privatised Karachi Electric Supply Company (KESC) and their political allies have occupied the main road in front of the club and set a camp under police protection. The road, located in the heart of the city, remains shut for traffic. All nearby buildings, which not only house the offices of some leading companies, but residential apartments as well, are also getting a taste of the “labour movement” — Pakistani style — against the reform and restructuring of KESC.

For several weeks, the Karachi Press Club (KPC) has been under siege. Hundreds of protesting workers from the privatised Karachi Electric Supply Company (KESC) and their political allies have occupied the main road in front of the club and set a camp under police protection. The road, located in the heart of the city, remains shut for traffic. All nearby buildings, which not only house the offices of some leading companies, but residential apartments as well, are also getting a taste of the “labour movement” — Pakistani style — against the reform and restructuring of KESC.

With naats, slogans and frenzied speeches blaring from loudspeakers at all odd hours, living on Sarwar Shaheed Road has indeed become an ordeal. “They are a nuisance to public life,” said an irritated resident of a nearby building. “But who cares about the public in Pakistan? If you have muscle power, the support of the ruling party and goons at your disposal, you can get away with murder.”

The frustration is not just confined to ordinary citizens. Journalists, who by and large are sympathetic to the workers’ cause, have also been at the receiving end of this unique struggle being waged under the patronage of provincial authorities and the Pakistan Peoples’ Party (PPP).

“They beat up journalists and KPC staff members when we tried to stop them from barging into our premises,” said Tahir Hasan Khan, president of KPC. “Now many members have stopped coming here because they find the major road closed. We have to shut the main gate because they demand food, tea and even toilet facilities. When we approached the police, we were told that they have been directed to facilitate the protesters. We have nowhere to turn to.”

But the woes of KPC members are just a tiny detail of the bigger picture called Karachi, which has seen its worst power outages in recent years, as the protesting workers went on an organised campaign to sabotage and disrupt the power supply. The KESC Collective Bargaining Agent’s (CBA) armed workers have damaged Pole Mounted Transformers (PMTs), high tension cables, maintenance trucks and feeders across the city, resulting in the worst power outages lasting up to six to seven days at a stretch in various neighbourhoods. At several places, KESC offices were forcibly shut down and the technical staff were beaten black and blue by armed men, who wanted them to stay away from work. Police and other law enforcement agencies, in most cases, looked the other way, or arrived only after the miscreants had completed their mission of destruction.

The disruption in power supply led to spontaneous protests, especially in the middle and low income neighbourhoods where a vast number of people do not have generators to light up their homes and run small businesses.

The situation was reminiscent of the ugly events of January this year when violent protesters ransacked KESC headquarters in the presence of security personnel. At that time, the PPP-led coalition forced the KESC management to reinstate more than 4,000 non-core employees, whose services were terminated following the outsourcing of their functions as part of the organisation’s restructuring drive. However, KESC had made it clear even then, that the government’s decision — based on political expediency — was unacceptable and should not be considered as a solution.

The non-core employees included bill distributors, drivers, security staff and sweepers whose jobs were given on contract to specialist companies. The KESC management said that by freeing itself from non-core operations, it wanted to concentrate on the core function of ensuring power supply in the megapolis. The decision made business sense as it reduced the head count from 17,000 to 13,000 and allowed the company to expand its technical services by hiring fresh staff where required.

According to KESC sources, the total cost of outsourcing is Rs 250,000, less than the amount spent on just the overtime and job-specific allowances of non-core employees. Once the plan is fully implemented, the company could save a substantial amount in salaries and other perks given to these employees, many of whom were ghost workers as well as those who worked for just two to three hours a day, but still claimed eight hours overtime daily.

“The protest is uncalled for because this time around we have not sacked any employee,” says a KESC spokesperson. “We just stopped the overtime and job-specific allowances of these staff members as these functions were outsourced. The outsourcing also helps in preventing meter tampering and installation of illegal connections.”

But the decision proved a blow to the vested interests at KESC, where all the major political parties, including the ones in the ruling coalition, have contributed to overstaffing and corrupt practices. The CBA says that putting employees in the surplus pool remains unacceptable. It also demands reinstatement of those employees who were sacked on charges of misconduct and violence.

To complicate an already complicated situation, some key leaders of the PPP as well as the opposition parties visited the protesting workers to show their support and avail cheap photo opportunities without understanding the issue and its impact on the overall investment and business climate of the country, which is caught in the low growth and high inflation cycle.

As a private-run organisation, the KESC has every right to decide its human resource policy and restructuring plan. It offered a voluntary separation scheme to the employees, under which, each employee would be given a minimum of Rs 700,000 to 4 million — according to seniority — on leaving the organisation. But the political parties-backed trade unions forced workers to reject it.

The government’s policy of arm-twisting the KESC through its labour unions and local leaders is in contrast to the precedence set in other organisations, including the privatised banks and even state-run natural gas distribution companies, where non-core functions such as security and bill distribution have been outsourced.

There is a complete disconnect between the government’s policies and deeds. On paper, it wants to boost foreign and local investment in the country and privatise state-run institutions, but its leaders appear bent upon scaring investors away by sponsoring and promoting unlawful activities and hostile statements.

Dr Ashfaque Hasan Khan, a leading economist who served as an advisor to the finance ministry, maintains that the PPP government should close down the ministry of privatisation and the board of investment if it wants to treat investors in such a shabby manner. “Who will want to invest in Pakistan, if the government fails to honour its commitment and provide security to investors?” asks Dr Khan.

Flawed populist policies, corruption and overstaffing have already wrecked the majority of the public sector enterprises, which are being kept afloat on subsidies. The top eight entities alone needed an injection of more than Rs 250 billion — which is higher than the total development expenditure of the country for the fiscal year 2010/11 (July-June). If privatised institutions like the KESC are not allowed to revamp and restructure to cut their losses and make profits, it will defeat the whole spirit and purpose of privatisation. Commercial organisations are not run as charities or job-providing bureaus. They operate or fail on the basis of profit and loss — a basic economic principle which many of our politicians fail to understand.

The KESC, in which the Dubai-based private equity firm Abraaj Capital has 50% shares and management control, has already invested more than 600 million in improving the power utility systems over the last two years. It should be encouraged to invest more and ensure a turnaround in its services to get Pakistan’s industrial and commercial hub going. An increased inflow of investment, badly needed by Pakistan, will help create new employment opportunities, which will offset the short-term bitter decision of the sacking of employees. Standing up for labour rights does not mean allowing ghost workers to draw salaries, file false overtime claims, indulge in corruption, break laws and resort to violence. Supporting a corrupt labour mafia is a recipe for economic disaster. The PPP government needs to ensure the writ of the law and provide protection to legitimate and lawful businesses to attract foreign and local investment and restore Pakistan’s credibility.

Related Post:

Tags: KESC, labour dispute, electricity theft, Tayyab Tareen, KESC privatisation

Amir Zia is a senior Pakistani journalist, currently working as the Chief Editor of HUM News. He has worked for leading media organisations, including Reuters, AP, Gulf News, The News, Samaa TV and Newsline.