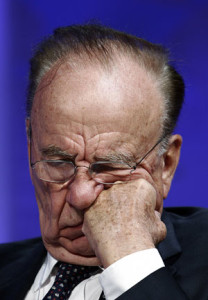

Rupert Murdoch and the Future of News International

By Mahir Ali | News & Politics | Opinion | Viewpoint | Published 14 years ago

Although predictions about the impending demise of Rupert Murdoch’s media empire may well be exaggerated, there can be little question that it has suffered serious blows in Britain during the past month, and aftershocks from the quake are likely to be felt for a long time to come. It is perfectly possible that in the years ahead the demise of the News of the World (NoW) could be signposted as the beginning of the end, at least as far as News Corporation’s newspapers are concerned.

Although predictions about the impending demise of Rupert Murdoch’s media empire may well be exaggerated, there can be little question that it has suffered serious blows in Britain during the past month, and aftershocks from the quake are likely to be felt for a long time to come. It is perfectly possible that in the years ahead the demise of the News of the World (NoW) could be signposted as the beginning of the end, at least as far as News Corporation’s newspapers are concerned.

The potentially fatal blow was struck by revelations that Glenn Mulcaire, a private investigator hired by the NoW, hacked into the mobile phones of hundreds of people in order to listen to recorded messages which, in many cases, were used as the basis for reports published in Britain’s highest-selling Sunday tabloid.

When Mulcaire and the newspaper’s royal correspondent, Clive Goodman, were sentenced to jail in 2007 on the charge of hacking into the mobile phones of people associated with the royal family (including Prince William), NoW claimed that Goodman was a rogue reporter using methods that the paper’s management did not condone. Allegations that Goodman’s behaviour was part of journalistic culture were not pursued at the time by Scotland Yard.

It has since turned out that the police had good cause not to examine NoW affairs too closely, given that the newspaper’s news-gathering strategies included paying cops for information. The resignations last month of London’s Metropolitan Police chief and his deputy are now part of the revived story, which sprouted legs at the start of the year, thanks in large part to the persistence of a very different newspaper, The Guardian, and its reporter Nick Davies — a likely recipient of multiple journalism awards in the year ahead.

The first casualty this year was the British prime minister’s chief spin doctor, Andy Coulson — a former editor of NoW who had been hired as communications director despite the misgivings of leading Liberal Democrats as well as The Guardian. Coulson had resigned from NoW in 2007 in the wake of the initial hacking scandal, albeit without acknowledging culpability. He had taken over as editor four years earlier, replacing Rebekah Wade, who had been named editor of NoW’s daily sister, The Sun.

Now known by her married name, Rebekah Brooks, she became the chief executive of News International, News Corp’s British subsidiary, in 2009. News Corp also owns the upmarket newspapers The Times and The Sunday Times. Like Coulson, she too has denied all responsibility for the nefarious goings-on at NoW.

When Rupert Murdoch arrived in London last month to personally tackle the biggest embarrassment his empire has hitherto faced, he was asked by the media scrum what his foremost priority would be. He pointed at Brooks and said, “She is.” Although it seemed obvious her position had become untenable, Brooks was not fired — she apparently offered to resign, but Murdoch pooh-poohed the idea. It was a couple of weeks later that her head rolled, along with that of senior News Corp executive Les Hinton, who had been head of News International before being named CEO of Dow Jones once Murdoch acquired it.

This was an unprecedented twin blow for the media mogul, whose association with Hinton goes back to the 1950s, when the latter, as a teenager, used to fetch lunchtime sandwiches for his young boss in Adelaide. That’s where Rupert began his journey as a press proprietor — he was still a student at Oxford when his father, Sir Keith Murdoch, died, leaving him a struggling evening tabloid in the South Australian capital.

The young Rupert Murdoch is believed to have harboured socialist ideals; his Oxford digs were reputedly decorated with a Lenin bust. He evidently lost little time in acquiring capitalist nous: not only did he succeed in reviving the fortunes of The Advertiser in Adelaide, but he also embarked on a shopping spree, buying up newspapers in other Australian cities. By the mid-1960s, he had launched the country’s only national newspaper, The Australian. News Corp’s Australian subsidiary, News Limited, owns about 70% of the national press, a degree of media concentration unparalleled outside communist countries.

When Murdoch turned his gaze to foreign markets, News of the World — a scurrilous broadsheet that had become the highest-selling English-language newspaper in the world in the postwar years — caught his attention. It became his first overseas acquisition, followed by The Sun, a tabloid notorious for devoting page three to photographs of topless women. The Times and its Sunday sister followed more than a decade later, in the early years of the Thatcher era.

Margaret Thatcher did not need to ask Murdoch for favours: her union-bashing agenda held a natural appeal for him, not least when he faced mass industrial action in the early 1980s after deciding to shift operations from Fleet Street to Wapping. The print unions’ insistence on sticking with old technology may have been fatuous, but Murdoch’s ruthlessness in enforcing the shift warmed the cockles of Thatcher’s heart. His newspapers, meanwhile, went way over the top in denigrating Labour Party leader Michael Foot. The propaganda continued after Foot made way for Neil Kinnock, climaxing with The Sun’s devastating front-page pronouncement on election day in 1992: “If Kinnock wins today, will the last person to leave Britain please turn out the lights.”

Although Thatcher’s successor, John Major, wasn’t a hot favourite in the Murdoch household, it was really Tony Blair’s ascendancy that made Major an appealing bet for Murdoch. Blair fawned on Murdoch, going out of his way to demonstrate his right-wing credentials. It has been reported that prime minister Blair spoke to Murdoch thrice in the week when he officially announced his support for the invasion of Iraq. But that was just a meeting of minds. It’s considerably more significant that Murdoch’s opposition is what thwarted Blairite Britain’s closer integration with the European Union.

Blair’s successor, Gordon Brown, who has lately become a leading critic of News International, was keen enough to fraternise with Murdoch, but the mogul decided to revive his natural Tory allegiance. David Cameron not only hired Coulson, he also socialised with Brooks as well as James Murdoch — Rupert Murdoch’s son and the head of News Corp’s European and Asian operations. When News Corp, which owns 39% of the British satellite television provider BskyB, wanted to buy the remaining 61%, and it emerged that business secretary Vince Cable (a Liberal Democrat member of the coalition) was opposed to the deal, Cameron quickly passed on responsibility to a more amenable minister. In recent days, though, the prime minister himself had to declare that it would be best for the Murdochs to withdraw their offer.

They did. The question now being asked in Britain is whether News Corp is fit to own the substantial proportion it already possesses. And, after the closure of NoW, it is now rumoured that Murdoch may wish to wash his hands of his remaining British newspapers by selling them off.

The crunch in Britain came when it emerged early last month that among the phones hacked was that of Milly Dowler, a schoolgirl who went missing in 2002 and was subsequently found dead. Not only had an NoW employee listened to her voicemails, but he had actually deleted a few in order to accommodate fresh ones — thereby interfering with police investigations and, even worse, giving the girl’s parents false hope. Evidence has subsequently emerged of efforts to hack the phones of war and terrorism victims. The notion that 9/11 victims might have been subjected to this treatment has prompted inquiries in the US, and calls for the same in Australia.

Illegal intrusions into the privacy of celebrities did not perturb Britons very much, but the Dowler hacking was a step too far. As advertisers began to withdraw their patronage from NoW, Rupert Murdoch decided to kill the newspaper.

Cameron, after initially resisting calls for a public inquiry, has instituted not one but two — meanwhile distancing himself from the Murdoch empire. It is not entirely inconceivable that his head, too, will roll at some point — perhaps in connection with the damning allegations that Coulson wasn’t subjected to the rigorous vetting normally required for his role.

Then there is the police angle: NoW appears to routinely have paid officers for information. What’s more, it employed Coulson’s deputy, Neil Wallis (arrested last month) as senior adviser at Scotland Yard.

It does not necessarily follow, though, that the inquiries will put paid to the nexus between sections of the media, the police and government.

The excesses associated with NoW, meanwhile, owe a great deal to Britain’s tabloid culture, whereby a bunch of newspapers that rarely tackle anything serious are constantly competing in the quest for salacious “exclusives,” usually focused on who is sleeping with whom. There are, of course occasional exceptions such as the NoW sting last year that exposed the involvement of three Pakistani cricketers in spot-fixing.

A distinction must obviously be drawn between the ideological extremism of Murdoch’s organs — including the appallingly reactionary Fox News network in the US — and violations of the law. However much one might detest Fox and the political stances adopted by the Murdoch press (which couldn’t possibly be a coincidence — the notion that Rupert permits editorial independence is a fantasy), they have a right to be opinionated. Illegality, on the other hand, is not an option that can reasonably be condoned.

The schadenfreude that has greeted last month’s revelations and developments, including a parliamentary committee hearing for Rupert and James Murdoch, as well as Brooks, is perfectly understandable, even though much of it emanates from those ideologically opposed to Murdoch’s nasty agenda. It is important to remember, however, that his troubles in Britain stem from violations of the law, rather than right-wing extremism.

Rupert Murdoch, meanwhile, is 80 now, and it is widely assumed that his nostalgic attachment to newspapers alone explains why they remain intact. Neither Murdoch nor this tendency will survive indefinitely.

In trying to surmise Rupert Murdoch’s antecedents, Randolph Hearst and Lord Rothermere — not to mention the fictional Charles Cane — come to mind. His influence may be exaggerated, but it is certainly not negligible — in Britain, Australia or the US. It will eventually wither away and the current British mood will push it along. What the future holds for Murdoch’s media assets meanwhile remains to be seen — but chances are that the newspaper component will steadily decrease. The TV stations are likely to survive. Whatever goes, though, will be greeted with the slogan: “Good riddance!”

It is widely claimed that Murdoch has been good for newspapers. That assessment cannot lightly be dismissed. But, on balance, something his publications instinctively shrink away from is a multiplicity of opinions. Hopefully that at least will change at some point. And if and when it does, it can be attributed to a desire to be ethical as well as adventurous.

This article was originally published in the August 2011 of Newsline issue under the headline “The Rupert Effect.”

Mahir Ali is an Australia-based journalist. He writes regularly for several Pakistani publications, including Newsline.