Book Review: Amal Unbound

By Nudrat Kamal | Bookmark | Published 7 years ago

It is a bit of a miracle that a book like Aisha Saeed’s Amal Unbound exists. A novel written in the West  about the life of a Pakistani girl in a village in Punjab, which manages to sidestep and often downright subvert damaging stereotypes about Pakistanis and, instead, creates a nuanced, multi-faceted narrative and characters that feel like real-life, breathing people, is a rare occurrence. A children’s novel that successfully explores indentured servitude, gender and class inequality and the corruption of the feudal system in Pakistan without tipping too far into the fetishisation of suffering, and instead skilfully maintains a balance of hope and optimism with a keen awareness of the inequities of the world, is even rarer.

about the life of a Pakistani girl in a village in Punjab, which manages to sidestep and often downright subvert damaging stereotypes about Pakistanis and, instead, creates a nuanced, multi-faceted narrative and characters that feel like real-life, breathing people, is a rare occurrence. A children’s novel that successfully explores indentured servitude, gender and class inequality and the corruption of the feudal system in Pakistan without tipping too far into the fetishisation of suffering, and instead skilfully maintains a balance of hope and optimism with a keen awareness of the inequities of the world, is even rarer.

Conversations about South Asian writing in the West, at least here in the subcontinent, centre around fiction written either by a writer of the South Asian diaspora (Jhumpa Lahiri, for example) or by a South Asian writer who is able to move frequently and easily between the subcontinent and the West (Kamila Shamsie, Amitav Ghosh, Mohsin Hamid). In both cases, however, the fiction which is talked about is high-brow, literary fiction.

What is mostly absent from these conversations is writing from other genres of fiction, often considered less literary — genres such as fantasy, science fiction, and now, with Saeed’s Amal Unbound, children’s fiction (or, more specifically, middle-grade fiction, as the category is officially termed, which is aimed roughly at children from the ages of 8 to 14). In recent years, there has been a surge of South Asian writing in these genres, from historical mysteries set in 1920s Delhi (The Widows of Malabar Hill by Sujata Massey) to fantasies set in a Taliban-ruled north western Pakistan and Afghanistan (The Khorsan Archives by Ausma Zehanat Khan). South Asian American writers are writing science fiction novels and romances and novels for young adults, including Pakistani American Saeed’s own debut novel Written in the Stars, in which the young main character’s conservative immigrant parents whisk her away to Pakistan to try and force her to marry a desi boy.

This access to greater space in western publishing for South Asian voices is a welcome one, given the misinformation and misrepresentation of South Asian people in dominant western narratives — narratives that allow only certain stories of suffering and terrorism and poverty to be told about us. And this space has been hard fought for by writers of South Asian descent, including Saeed herself, who is a founding member of We Need Diverse Books, a non-profit initiative that advocates for greater diversity in children and young people’s fiction in the US.

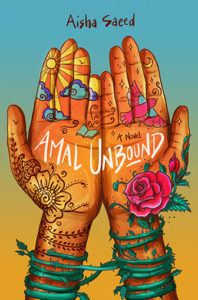

Amal Unbound (with its beautifully drawn cover by Pakistani artist Shehzil Malik) is about 12-year-old Amal, the brightest student in a girl’s school in her village, an Urdu poetry aficionado who has dreams of becoming a teacher. Being the eldest daughter in her family, her dreams are temporarily put on hold when her mother gives birth, and she has to stay at home to look after her sisters and manage the household while her mother recuperates. Frustrated at being pulled out of school, and grappling with her parents’ evident disappointment at the birth of yet another girl, Amal inadvertently lashes out at Jawad Sahib, the son of her village’s powerful and corrupt landowner. Angered by the insult, the son decides that Amal can pay off the insult (as well as the loans Amal’s father was forced to take from the landowner) by working at his large estate as a servant. Deprived of all she cherishes, Amal must navigate the complex dynamics amongst the coterie of servants at the estate, as well as learn to work for a corrupt and egomaniacal man and his mother, all the while realising that the debt she is under might never be fully paid off.

Amal Unbound’s greatest accomplishment is that, despite exploring issues of class, gender, feudalism and corruption, it is very much Amal’s story, the depiction of her world and her own journey, as opposed to a novel that heavy-handedly seeks to educate the West on how things work in Pakistan. Saeed’s descriptions of Pakistani village life and relationships amidst all the villagers, are full of warmth and life, and you never get the sense that the narrative is overburdened with the task of illuminating a western audience with something foreign or strange. The references to Iqbal and Ghalib, and to nihari and chicken karhai, feel organic and natural, instead of forced and jarring (something a lot of desi writers writing in English struggle with). Amal is a skilfully drawn character, her love for learning and her optimistic determination making her easy to root for. Saeed focuses on Amal’s relationships, with the younger servants, Nabila and Fatima (one of whom is unhappy with Amal’s arrival for reasons of her own), and the kindly Nasreen Baji (whose personal maidservant she works as), as well as Amal’s own journey where she has to rely on her own resourcefulness and courage in the face of odds.

While Jawad Sahib’s treatment of Amal never veers into the truly horrific, the narrative has enough realism to create the tension necessary and appropriate for a story aimed at children and pre-teens. For instance, as Amal gradually learns, from some of the other servants who have been paying off debts for years, indentured servitude is a trap where every day in which they work they accrue more debt than they owe for boarding and lodging at the estate, making it virtually impossible for workers or their families to ever have enough to pay off the debt and thus ensuring, in many cases, life-long servitude.

This is precisely why Amal Unbound comes as such a pleasant surprise — it is no mean task to balance a recognition of the harrowing inequalities that exist in feudal Pakistan while maintaining an outlook of hope and optimism, that is the hallmark of any truly great children’s book. Saeed’s book is a valuable addition to the pantheon of children’s literature not only in the West (where it is already on The New York Times’ bestsellers’ list), but also here in South Asia.

Nudrat Kamal teaches comparative literature at university level, and writes on literature, film and culture.