House Divided

By Ali Arqam | Cover Story | Election Special | Published 7 years ago

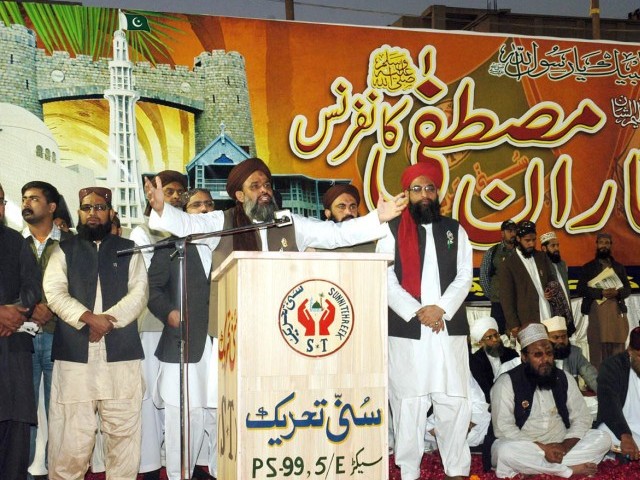

Reviving the religious conglomerate: The MMA launches its election campaign.

Jibran Nasir, a Karachi-based lawyer and human rights activist contesting elections from National Assembly constituency NA-247 and Provincial Assembly constituency PS-111, visited Hijrat Colony in Karachi during his electoral campaign. He was talking to traders and shopkeepers about his work as a lawyer in the Shahrukh Jatoi and Naqeebullah Mehsud cases, when a supporter of the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) asked him to state his position on the issue of Khatm-e-Nabuwwat. Jibran responded that no one had the right to question him on his faith, which was strictly between him and Allah. This led to a heated argument, but the crowd of young supporters accompanying Jibran started chanting slogans and accompanied Jibran to other shops in the area.

TLP chief and firebrand cleric, Khadim Hussain Rizvi, took a similar stance during a political talk show, asking the host direct questions about his faith. However, it’s not only the TLP that resorts to simplistic notions when it comes to the issue of faith, dragging it into politics in a bid for support.

The revived conglomerate of religious political parties, the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA) has kickstarted its campaign with banners and posters bearing pictures of their electoral symbol, kitab (Book), with the message, “Make the Book your pathfinder.”

The MMA is a broad-based alliance of mainstream religio-political parties, with representation from almost all the major sects, including the Sunnis (both Barelvis and Deobandis), Shias, and the Salafis (the Ahl-e-Hadith). After the 2002 elections, it managed to form the government in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and a coalition government in Balochistan. It had representation in Punjab and in Sindh as well. In the latter case, all its representatives won from the provincial capital, Karachi, snatching some constituencies from the MQM, in the heart of its support base in Karachi Central. The success was due mainly to the Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) and Jamiat Ulema-e-Pakistan-Noorani (JUP-N) drawing support from constituencies they had won in the ’70s, before the rise of the MQM.

At the time, another religious party that irked the MQM and dented its vote bank was the radical Sunni Barelvi group, Sunni Tehrik (ST). Though it didn’t win a constituency, it did manage to get the fourth highest number of votes after the MQM, the PPP, and the MMA.

The ST was formed by Saleem Qadri, a former member of the JUP-N, in the early ’90s, and his companions included Abbas Qadri, Iftikhar Bhatti, Akram Qadri, and Waheed Qadri. There are different theories about the genesis of the ST. It initially came forward as a group that vowed to defend the mosques, seminaries, and shrines of Sufi saints against the onslaught of the highly militarised Deobandi sect at the forefront of the jihadi wave in Afghanistan and Kashmir. Various jihadi and sectarian outfits and their trained cadres set about increasing their footprint in Karachi, expanding their network of seminaries and mosques in newly inhabited informal settlements, as well as taking over mosques from their rivals, the Barelvi sect, in formal settlements and localities.

Another theory suggests that the ST emerged initially with the support of the MQM, as they were apprehensive of the rising influence of Deobandi jihadi and sectarian outfits in their areas of support.

Events of later years could be presented in support of both theories, as the ST too engaged in armed conflict and turf wars with Deobandi jihadi and sectarian outfits and the MQM lost its workers and central leadership in similar conflicts.

The Sunni Tehrik was one of the parties that dented the MQM vote bank.

The ST’s organisational structure followed in the footsteps of the MQM. It set up an organised mechanism to extort money from traders and businessmen. These tactics brought them into confrontation with the MQM, with armed clashes resulting in the murder of workers from both sides. ST also clashed with rival Deobandi outfits, like the Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM) and the Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP), over the control of mosques. One such dispute over a mosque in Bahadurabad led to the assassination of Saleem Qadri, the Sunni Tehrik’s founder.

It was due to these tactics that ST was put on the watch list when the military government of General Pervez Musharraf banned jihadi and sectarian outfits. Political rivalry with the MQM and sectarian confrontation with other parties led them to a solo flight in the 2002 general elections.

The ST leadership was decimated by the 2006 Nishtar Park incident, when a bomb exploded near the stage during the annual congregation of Milad Sharif, the birthday of the Holy Prophet (PBUH), which resulted in the elimination of almost the entire central leadership of the ST, along with prominent members of other Barelvi groups.

The ST didn’t recover from that disaster for several years, and split into two groups. Allama Sarwat Ejaz Qadri, who had assumed the party leadership after the Nishtar Park incident, renamed his faction Pakistan Sunni Tehrik (PST), while the breakaway faction led by the son of slain ST leader Saleem Qadri, Allamma Bilal Saleem Qadri, took the old name, Sunni Tehrik.

The PST got a new lease of life in the post-Mumtaz Qadri execution scenario, when it organised protests and sit-ins, along with the TLP and other Barelvi groups. It also demonstrated its muscle power in Karachi, in November 2017, after a crackdown on the Faizabad sit-in evoked protests at multiple points in Karachi, bringing the city to a halt.

Coming to elections 2018, the PST has formed an alliance with the Muttahida Nifaz-e-Nizam-e-Mustafa Mahaz (MNNMM) and with Barelvi groups led by Sahibzada Abul Khair Zubair, Haji Hanif Tayyab, Engineer Samiullah, Maulana Fazal Kareem, and Sahibzada Hamid Raza. The alliance will field independent candidates, as it is not registered with the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP).

The TLP will also field candidates across the country. The way it has managed to get votes in by-elections indicates it may cause a dent in the vote of mainstream political parties, who have vied for conservative religious votes through the Sufi clans, mostly in Punjab.

The TLP will field candidates from across the country.

Khadim Hussain Rizvi clarified that the TLP wouldn’t just field religious clerics in the elections. According to him, “Only one per cent of the applicants for TLP tickets are religious clerics, most are ordinary individuals who vow to defend their faith regarding the finality of the Holy Prophet (PBUH). They have started a campaign asking their supporters to fill a form, the Vaada Form, to give a pledge that they would keep their religious aspirations and matters of faith above all affiliations while casting their vote.”

In its 20-point manifesto, the party patron-in-chief, Pir Afzal Qadri, vowed to establish a new ministry of Amar bil Maroof wa Nahi Anil Munkar (Enjoining what is deemed right, and forbidding what is deemed wrong) and vowed to assign it powers to prevent wrongdoing. It seems like a Taliban type arrangement, similar to the one practiced by clerics from Lal Masjid and their disciples in Islamabad markets, burning CDs and attacking salons and massage parlours.

In Karachi, the contest for the Barelvi vote between the PST (which has joined the MNNMM) and the TLP may dent the MMA vote bank in the old city areas, but in most constituencies it will act as a spoiler for the mainstream parties, the PPP and the MQM-P.

The leading candidate of PRHP from Karachi, Allama Aurangzeb Farooqui.

The Shia vote is also split between the Tehreek-e-Islami (former Tehreek-e-Nifaz-e-Fiqah Jafaria) and Majlis Wahdat-e-Muslimeen (MWM). The former is part of the MMA, while the latter has managed to draw support in Karachi, and won a provincial assembly constituency in the 2013 general elections, in the Hazara localities of Quetta. The MWM has been more active in recent years regarding the issues of target killing of Shias and the enforced disappearances of Shias returning from pilgrim sites in Iran, Iraq, and Syria. Their support, however, has been affected by their inability to resolve these issues, and to work for the prevention of target killing of Hazaras.

The JUI-F has its own competitors from the former Ahle Sunnat Wal Jamaat (ASWJ), rechristened Pakistan Rah-e-Haq Party (PRHP). PRHP candidates Aurangzeb Farooqui, Masood-ur-Rehman Usmani, Maulana Taj Muhammad Hanafi, and others are contesting from constituencies won by the JUI-F candidates from the MMA platform. Interestingly, in the 2013 general elections, the ASWJ candidates — contesting from the Muttahida Deeni Mahaz platform, an alliance formed by the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam-Samiul Haq (JUI-S) – bagged more votes than JUI-F in those constituencies.

Aurangzeb Farooqui’s nomination papers were challenged for concealing information about his implication in an FIR for the murder of Khurram Zaki, an outspoken Shia activist. He was later cleared and will contest elections from the NA-238 and PS-91 constituencies in Malir district, where the party had won three union councils in the local bodies’ elections.

Abul Khair Zubair of JUP-N will contest against the MQM in Hyderabad.

As if all this were not enough, there is a new entrant to the city’s electoral scene, the Allah-o-Akbar Tehrik (AAT), the new avatar of the Jamaat-ud-Dawa (JuD), after their political offshoot, the Milli Muslim League (MML) was refused registration by the ECP. The AAT has fielded five candidates for National Assembly constituencies from Karachi, and 17 for the Sindh assembly.

The divide among parties vying for votes on religious grounds could harm candidates of the JI, who are contesting from the MMA platform. The Karachi chapter of the JI has, in recent years, focused on civic issues and provision of basic utilities. The party has been at the forefront of the campaign for the issuance of National Identity Cards to residents of Karachi, through public agitation. They have also pursued legal action against K-Electric, and raised the issue of chronic water shortages in the city and the government’s inability to address the problem. The JI’s central leadership has also attempted to gain leverage and exploit religious sentiments, by calling for a protest against the death sentence awarded to Salmaan Taseer’s assassin, Mumtaz Qadri. However, now a plethora of religious groups are poised to challenge the JI’s standing in the coming elections.

Ali Arqam main domain is Karachi: Its politics, security and law and order