The Curse of the Electables

By Aamer Ahmed Khan | Cover Story | Newsbeat National | Published 7 years ago

The evil that descended on Pakistan in the shape of General Zia-ul-Haq on July 5 1977 left this blessed land just over 11 years later but sadly, Pakistan refuses to let go of a man who brought nothing but ruin to it. Nearly 30 years after his death, we continue to embrace his legacy, be it in the shape of public morality, private religious beliefs or political inclinations. The recent rise of the so-called “electables” is the latest manifestation of his dark and dreadful legacy.

Why call it dark and dreadful? Let us rewind to 1985, when the cancer of electability was first introduced into the country’s body politic by a dictator flailing for a lifeline after his referendum a year earlier had technically secured him a fresh five-year presidential term but had turned his entire regime into a laughing stock for a nation itching to break out of seven years of the most bizarre form of political and religious obscurantism ever suffered by Pakistan. He knew he had to acquire a new face for his regime but almost all of Pakistan’s mainstream political parties were united against him in the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD) that by then had wrested back considerable space in public discourse, if not politics, within a mere two years after launching a failed agitation against the dictator.

Elections seemed to be the only way out but if held properly, they also appeared to be a short and direct route to the gallows for General Zia. Using all of the ingenuity that had enabled him to corrupt contemporary literature, performing arts, cinema and school syllabi with jihadi rhetoric and use religion as a devastating political weapon, he came up with the idea of holding party-less elections to create a façade for his ill-gotten presidential term. Playing right into his hands, a move that the likes of Benazir Bhutto were to regret to their last day, the MRD boycotted the elections to allow the dictator an uncontested cauldron in which to bubble his vile apolitical brew.

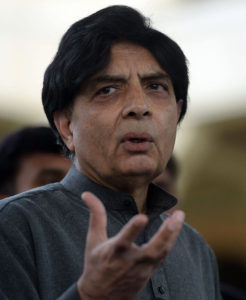

Meet Chaudhry Nisar and Sheikh Rashid, two of the most recognisable faces today to have emerged from that cauldron, like ghouls that were to haunt Pakistani politics for the rest of their days. Between them, they represent an entire breed of political opportunists, for whom political ideology only meant being in power. There was no right-wing or left-wing for them, no progressive or conservative agendas, no interest greater than their own and no loyalty for anyone but themselves.

Meet Chaudhry Nisar and Sheikh Rashid, two of the most recognisable faces today to have emerged from that cauldron, like ghouls that were to haunt Pakistani politics for the rest of their days. Between them, they represent an entire breed of political opportunists, for whom political ideology only meant being in power. There was no right-wing or left-wing for them, no progressive or conservative agendas, no interest greater than their own and no loyalty for anyone but themselves.

However, as with most creatures real or imagined, ghouls too cannot survive in a vacuum. And as the farcical parliament that resulted from the February 1985 elections started to collapse, General Zia tried to find a glue to hold it together by creating two apolitical groups in the parliament — the Official Parliamentary Group (OPG) and the Independent Parliamentary Group (IPG) — to lend this rudderless ship some sense of direction. While the OPG was supposed to represent the government, the IPG was tasked to act as an opposition. Predictably, it was a box-office disaster and the dictator soon found himself scavenging for a better adhesive to hold the simulacra he had created in place.

Very, very reluctantly, he eventually allowed the revival of political parties, banding together a panicky parliament under the banner of Pakistan  Muslim League. However, it was only a name, devoid of any political ideology or direction, and fated to collapse against the steady pressure building up on the military regime after the return of Benazir Bhutto in 1986. In another insidious move to hold the loyalties of this individually elected horde, General Zia allowed development spending of public money to be routed through them in order to enable them to cement their hold in their respective constituencies. This was the death blow that continues taking a toll on politics to this day.

Muslim League. However, it was only a name, devoid of any political ideology or direction, and fated to collapse against the steady pressure building up on the military regime after the return of Benazir Bhutto in 1986. In another insidious move to hold the loyalties of this individually elected horde, General Zia allowed development spending of public money to be routed through them in order to enable them to cement their hold in their respective constituencies. This was the death blow that continues taking a toll on politics to this day.

The dictatorial ideology of “the saviour,” of one man being the answer instead of a system, of personal benevolence being the key to relief instead of procedural redress, of being in power becoming synonymous with being above the law, thus started to seep from the GHQ to the streets and bazaars of the country. From being the constituents of a legislative body, the people’s perception of their elected representatives turned to that of being their prime interlocutors with the state on day-to-day matters such as jobs, upkeep of streets and drains and escaping the rule of law in general.

By the time General Zia died in 1988, paving the way for Pakistan’s first party-based elections since 1977, the cancer of electables had spread to all corners of the country. And come the 1988 elections, people were talking as much about political parties as they were of the Cheemas, the Chatthas, the Kharals, the Jadoons, the Tammans, the Makhdooms, the Mehers, the Khosas, the Qureshis, the Gilanis and the Legharis. It is not without reason that despite being contested by political parties, the 1988 elections were reported by the print media of the times almost exclusively in terms of biradaris, clans and families. The PPP was going to win Gujrat not because of its promise of roti, kapra aur makan but because of the Pagganwallas. It was looking weak in Mianwali because it had failed to win over the Niazis. It would do well in southern Punjab because the Legharis, or the Qureshis or the Gilanis were backing it. In a hopelessly fragmented political theatre, Sindh was perhaps the only political act left because of its long years of steady opposition to the military junta. There was a reason why Zia protégés like Chaudhry Nisar and Sheikh Rashid won in the Punjab but his favourite lackey in Sindh, the Pir Sahib of Pagaro, was routed by a non-entity like Pervez Ali Shah. Primarily, it was these electables in the Punjab created by General Zia that helped prevent a runaway victory for Benazir Bhutto in 1988.

By the time General Zia died in 1988, paving the way for Pakistan’s first party-based elections since 1977, the cancer of electables had spread to all corners of the country. And come the 1988 elections, people were talking as much about political parties as they were of the Cheemas, the Chatthas, the Kharals, the Jadoons, the Tammans, the Makhdooms, the Mehers, the Khosas, the Qureshis, the Gilanis and the Legharis. It is not without reason that despite being contested by political parties, the 1988 elections were reported by the print media of the times almost exclusively in terms of biradaris, clans and families. The PPP was going to win Gujrat not because of its promise of roti, kapra aur makan but because of the Pagganwallas. It was looking weak in Mianwali because it had failed to win over the Niazis. It would do well in southern Punjab because the Legharis, or the Qureshis or the Gilanis were backing it. In a hopelessly fragmented political theatre, Sindh was perhaps the only political act left because of its long years of steady opposition to the military junta. There was a reason why Zia protégés like Chaudhry Nisar and Sheikh Rashid won in the Punjab but his favourite lackey in Sindh, the Pir Sahib of Pagaro, was routed by a non-entity like Pervez Ali Shah. Primarily, it was these electables in the Punjab created by General Zia that helped prevent a runaway victory for Benazir Bhutto in 1988.

However, despite Bhutto’s flawed politics in the early part of her career, the 1988 elections seemed to have started the process of recovery but for a stolen election in 1990, where an all-powerful military-backed presidency stunned the nation with an election result that few in Pakistan had anticipated and no one around the world could believe. Come the 1993 electoral battle and a chastened Benazir Bhutto, losing her wits against Pakistan’s powerful and manipulative military establishment, found herself conceding to the onslaught of this cancer. While she may have done the same to some extent in 1988, it was only in 1993 when her fatigue with fighting the cancer was all too visible as she entered into an alliance with a bunch of electables banded under PML-J and led by two of the principal beneficiaries of General Zia’s politics — Hamid Nasir Chattha and Mian Manzoor Wattoo. In doing so, for millions of voters across the country, she abandoned the dream of agenda-driven ideological politics, an abandonment that lashed back ferociously in 1997 as her voters refused to show up and the election landed Mian Nawaz Sharif with a two-thirds majority.

The PPP in 2002 and 2008 rode the same bandwagon, gradually eroding its political base, shored up temporarily by the sympathy vote generated by her assassination, only to end up in a situation where it is struggling even to put up enough candidates to contest all 272 seats. The resilience of politics, however, is underestimated only at one’s own peril. Mian Nawaz Sharif’s troubled relationship with the army, his defiant stand after a shamelessly orchestrated ouster and Imran Khan’s slogan for change, seemed to be once again pushing the cancer of electability towards remission. For a brief while, it appeared that between his call for change and Mian Nawaz Sharif’s defiance of the army’s interference, the 2018 electoral battle may once again turn to ideology as its principal weapon, but that was not to be.

Imran Khan’s decision to rely on the electables has come as a shot in the arm of a tumour that had taken a considerable beating in the last year or so. Had he stuck to his guns of introducing genuine change, aided by Mian Nawaz Sharif’s exception to military interference, Pakistan may well have expected a whole new crop of politicians spawned by ideology instead of personal expedience. But with one decision, he has taken Pakistani politics back by 30 years while appearing to be totally unmindful of the consequences. All he knows is that he must do whatever it takes to defeat the PML-N.

Imran Khan’s decision to rely on the electables has come as a shot in the arm of a tumour that had taken a considerable beating in the last year or so. Had he stuck to his guns of introducing genuine change, aided by Mian Nawaz Sharif’s exception to military interference, Pakistan may well have expected a whole new crop of politicians spawned by ideology instead of personal expedience. But with one decision, he has taken Pakistani politics back by 30 years while appearing to be totally unmindful of the consequences. All he knows is that he must do whatever it takes to defeat the PML-N.

In Robert Bolt’s famous play A Man for All Seasons, there is an interesting argument between Sir Thomas More and his son-in-law William Roper:

Sir Thomas More: “Yes! What would you do? Cut a great road through the law to get after the Devil?”

William Roper: “Yes, I’d cut down every law in England to do that!”

Sir Thomas More: “Oh? And when the last law was down, and the Devil turned ’round on you, where would you hide, Roper, the laws all being flat?

Whether the devil Imran Khan is chasing turns on him or not, by opting to pander to the curse of the electables, he has ensured that Pakistani politics remains helpless in the vicious grasp of a predatory elite that has cancerously sapped Pakistani democracy throughout its inglorious existence.