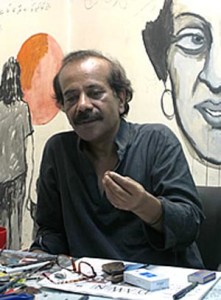

Profile: Feica

By Afia Salam | Art | People | Profile | Published 14 years ago

“I don’t want to be a great artist, I just want to be an artist,” remarked Feica, addressing the audience at his exhibition held at T2F in September. While he may not consider himself to be an exceptional artist, there are few who would contest that Feica is exceptional in his line of work as a political cartoonist.

“I don’t want to be a great artist, I just want to be an artist,” remarked Feica, addressing the audience at his exhibition held at T2F in September. While he may not consider himself to be an exceptional artist, there are few who would contest that Feica is exceptional in his line of work as a political cartoonist.

When Sabeen Mahmud asked me to moderate a discussion with Feica on the day of his exhibition at T2F, I thought it would be short and crisp; after all, Feica was a recluse — he hardly ever appeared at public forums and preferred his caricatures to do the talking for him. But I was in for a surprise and so was the audience that evening who listened to him in rapt attention for over two hours. This was certainly a different person from the Rafique I knew. Later, in a separate face-to-face with Newsline, Rafique Ahmed aka Feica (maybe it should be the other way around now) spoke of his journey from the conservative confines of his hometown Multan, to the otherworldly surroundings of National College of Arts (NCA) in Lahore and, eventually, Karachi.

Born in 1957 in Multan, Feica started his schooling there, but could never take to studies. According to him, he was “only interested in drawing,” for which he was even reprimanded by a family elder who thought he was doing something ‘haram.’ He credits his father for allowing him to pursue his dream and as soon as he passed his Matric examinations, he simply picked up a bag and some money, and landed up in Lahore. He had seen an NCA advertisement in a newspaper and armed with around 50 drawings in his portfolio, he applied for admission to the college. This was way back in 1973-74, when NCA admitted students who had passed their Matric exams. In later years, the admission criterion was changed to an intermediate degree.

Despite a totally different environment, Feica didn’t suffer too much of a culture shock due to the grounding he had received from home where values of swimming against the tide were upheld. This was the period when Shakir Ali was the principal, though he died soon afterwards. As far as creative expression was concerned, it was the golden period as the Bhutto era promoted liberal arts. However, the simple kid from Multan became quite confused when he was made to learn about Rembrandt, Dali, van Goh and Picasso. So, here too, like in Multan, he floundered at academics. There was a twinkle in his eyes when he said that despite this he proved very popular with the ‘bachiyan’ (girls) at NCA, as he used to draw for them on the sly. In fact, his teacher Colin David, once caught him in the act, but that was all part of student life. He gleefully informs me that the girl who topped the course never amounted to much as an artist, but look at where he is!

However, there was always one impediment in his journey to the top: the English language. He fondly recalls the pains the librarian took over him by telling him to read the newspaper aloud to himself. That way he would be reading, listening, as well as understanding simultaneously. His father had connected him to the librarian through a friend of his as he was concerned about how his small town boy would fare in the big city of Lahore. Within six months, Feica could understand the language fully well and was able to gel with his environment. Not only that, he became a sort of a trendsetter. Feica formed a group that came to be known as the kabaria (waste collector) group that would go around the college with a sack on their shoulders, collecting all the left over paints, pencils, crayons and any other material like coloured paper etc., which they would use in their own art work, especially in the hostel where the lifestyle was quite bohemian. He credits his teacher Khalid Iqbal with this suggestion as he taught them how to reuse dried paints and hone their skills.

His teachers were also a source of exposure to other arts like music; they welcomed students who came and shared the company of great ustads that visited the professors. Then again, being located next to the museum — as are most art colleges the world over — presented another opportunity for education.

After the kabaria stint, Feica discovered another way of spending his time constructively — this time outside of college. He found himself a spot and a model: Raffoo ki canteen at the corner of MAO College, and a man by the name of Dr Salim Wahid Salim. Apparently he was a student activist and had lost his mind after undergoing torture in the Shahi Qila during the Ayub regime.

“He wore an overcoat in the summers and he would abuse us and even throw stones at us,” recalls Feica. “His next of kin used to make a monthly payment to the canteenwalla for whatever he would eat from there.”

By the end of the first year in college, these activities gave way to serious work, which now had to be done ‘in camera’ so it wouldn’t be copied by others. Come 1975, NCA celebrated its centenary. It was a time of heightened political awareness, especially due to the arrival of Zia-ul-Haq and his brand of Islamisation, which threatened the creative arts. The right-wingers started smashing sculptures and objecting to drawing the human form. That is when calligraphy really took off and Sadequain, who until then had been painting nudes, immersed himself in the genre of calligraphy.

Having realised that he could never excel academically, Feica somehow managed to scrape through his thesis, received his certificate and in 1979, “I distributed all my paintings, picked up my bags and went off to Islamabad instead of Multan. I joined a newspaper The Muslim under Mushahid Hussain, and also started drawing for Zafar Sultani’s Ravish. When I had about Rs 7,000-8,000 in my pocket — a fortune in those days — I went off to try my luck in Karachi. There, I was passing by MNJ advertising, barged into Javed Jabbar’s room and insisted that I wanted to work there. He saw my work and I was hired immediately. That is where my association with Zohra Yousuf and the late Saneeya Hussain started.”

Says Feica, “When Zohra joined The Star, she asked me to freelance for it. Then she introduced me to Hameed Haroon who asked me to join The Star, and I did.” The Star of those days was dominated by females: Zohra Hussain, Tehmeena Hussain, Tasneem Ahmer, Fazila Naqi (now Gulraiz), Sehba Sarwar and myself. All of us would huddle in a corner of the room and do gup shup. Poor Rafique would want to join in the conversation, but he would immediately be shunted out of the ‘zenana dabba.’ He would protest loudly at being discriminated against as there was no other male member in the office he could ‘chill out’ with. He would depart with a sulky face, but that sulk never lasted — and thank God it didn’t, or we would have missed out on the hot and yummy home-cooked parathas and saag he would bring us from Multan. He would call us the day he was scheduled to return, asking us not to order lunch or bring in food. His mother would cook just before his flight time and pack the food, which would reach us, fresh and hot. Perhaps this was Feica’s way of saying thanks for all the effort we put into helping him buy gifts for his sisters before his trip home!

On a serious note though, those were the days of Zia’s pre-censorship era. The work was chaotic, but a lot of what was produced didn’t always make it into print. Despite the constraints, it was at The Star that Feica’s career really took off and, in his words, was “the beginning of my serious career as a cartoonist.” The repressive Zia era seemed to boost his creativity and spark rebellion, as was reflected in his cartoons. Feica also started freelancing with other publications like Dawn and the Herald, and teamed up with Anwar Maqsood to do cartoons for Hurriyet, the group’s Urdu newspaper. This was the time when Yousuf Lodhi — popularly known as Vai Ell — the political cartoonist par excellence also joined The Star, which was making waves despite the repression.

Feica left Star in 1986, went back to The Muslim in Islamabad, and then moved to the Frontier Post in Peshawar in 1987. There again he was joined by Vai Ell and Zahoor, who came in as an illustrator and became a cartoonist when Feica moved to Lahore in 1988. Somewhere along the way, he morphed from Rafique to Feica (short for Rafique), asking his editor to come up with the correct spelling for ‘Feica’ which incidentally is used as a pet name in the Punjab for Rafique. Another visible change, along with his new signature, was the addition of a balding character in his caricatures. Earlier, there was just the roving crow that was an incredulous witness to the events being portrayed by Feica. The introduction of the balding character set off a guessing game within the journalists’ fraternity. At T2F, he didn’t really let the cat fully out of the bag, when he said,“I made it so that ZIM, (Dawn’s Lahore editor), and Saleem Asmi (the editor), would each think it was based on them.”

Feica became friends with an American girl there and followed her to the US, where he spent the next two-and-a half years of his life, visiting museums and art galleries, and working. 1992 marked the end of his US sojourn and upon his return, the late Najma Babar introduced him to the then editor of Dawn, Ahmed Ali Khan, who hired him and he has been a part of Dawn since then. From a young, aspiring cartoonist who had to be given directions by the editor on what to draw and what not to draw, now he just sits in on editorial meetings and decides on his cartoon for the day.

Feica has travelled a lot, seen a lot, and lived life in relative peace. But like many young men who live a carefree life, with no responsibilities and no one to answer to, he too fell into substance abuse and alcoholism. He will remain eternally grateful to a friend for being his saviour and helping him get out of his drinking habit and drug problems by pulling him out of his surroundings and giving him an alternate platform, Radio FM 107, which the friends set up. With great willpower, Feica was able to not only leave those problems behind, but he also turned the station into a very successful, profit-making enterprise. He married a girl from the family who, according to him, is “very gentle and very religious.” However, he says, “She has adjusted very well with me.” A proud father of three children, he speaks in glowing terms about his daughter, whom he credits with possessing great talent, and who he says may follow in her father’s footsteps.

Feica thinks he has made the grade as a good artist, but his one grouse against society is that artists here are not looked after because art is considered to be a luxury. He would like to see the situation of artistes in his country change for the better.

This article originally appeared in the December 2011 issue of Newsline under the headline “Drawing From Life.”