In Focus: Pakistani Street Photography

By Zehra Nabi | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 14 years ago

Photospace gallery recently showcased works by four young photographers in an exhibition entitled ‘Street Theatre’. Street photography functions both as art and a form of social documentary, and this duality is perhaps most evident in Hameed Moinuddin’s work. Walls and gates dominate the foreground of his photographs, emphasising the distance between the photographer and his subject. He reveals, “I comment on the lack of safety in Karachi by shooting from behind closed doors.” The act of prying at people from a distance reveals a sense of vigilance that pervades crime-ridden Karachi.

Photospace gallery recently showcased works by four young photographers in an exhibition entitled ‘Street Theatre’. Street photography functions both as art and a form of social documentary, and this duality is perhaps most evident in Hameed Moinuddin’s work. Walls and gates dominate the foreground of his photographs, emphasising the distance between the photographer and his subject. He reveals, “I comment on the lack of safety in Karachi by shooting from behind closed doors.” The act of prying at people from a distance reveals a sense of vigilance that pervades crime-ridden Karachi.

But Moinuddin is not afraid to move closer and does so in his portrait of a drug addict that captivates the viewer with its dramatic composition and subject. However, a bolder photograph is not necessarily a better one, and some of Moinuddin’s relatively unassuming photographs, such as two small portraits of a woman, deserve more attention. On closer inspection, one finds it is not actually a woman but a eunuch — her face half-obscured by lens flare and bokeh (blur). This inadvertent “veiling” of the transvestite is ironically fitting since eunuchs are highy ostracised in Pakistan. Another highlight is a photograph of two boys playing with a ball. By cropping out everything but their shadows and outstretched arms, the image is divorced of playfulness and instead is replete with a sense of absence and anticipation. Moinuddin insists that photography is only a hobby for him, but he certainly has the discerning eye of a true photographer.

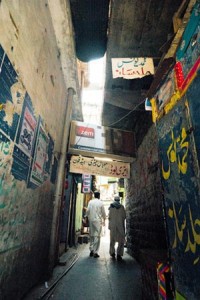

In Ali Sultan’s photographs, there is a prevailing sense of stillness, which can be attributed to his patience when snapping pictures on the streets. Rather than taking several photographs and later editing them, Sultan prefers to wait for the right moment to be captured and only takes a handful of photographs at a time. There are many textural details in his photographs, as seen in an image of tattered flyers layered over a wall or a portrait of a man in which each white strand of hair glows against his skin. In the latter, the high-contrast effect appears to be digitally manipulated and gives the figure a hardened, almost unreal, appearance.

In Ali Sultan’s photographs, there is a prevailing sense of stillness, which can be attributed to his patience when snapping pictures on the streets. Rather than taking several photographs and later editing them, Sultan prefers to wait for the right moment to be captured and only takes a handful of photographs at a time. There are many textural details in his photographs, as seen in an image of tattered flyers layered over a wall or a portrait of a man in which each white strand of hair glows against his skin. In the latter, the high-contrast effect appears to be digitally manipulated and gives the figure a hardened, almost unreal, appearance.

The contemplative quality of Sultan’s work echoes in Mobeen Ansari’s photography. Most of Ansari’s photographs are portraits and he reveals that since he has a hearing impairment, he likes to communicate through photography. When asked how he approaches strangers to photograph them, Ansari shares, “I just smile” — a tactic that Ali Sultan also employs to put his subjectsat ease. Ansari originally studied fine arts and this lends his work a painterly quality. A dramatic photograph of an elderly woman, her body cloaked by an ochre chaddar, is reminiscent of paintings by Rembrandt and Vermeer to the extent that it looks staged. But Ansari shares that he simply chanced upon this woman while exploring the streets of Rawalpindi. His other portraits appear less dramatic with the subjects, a guard and a fisherman, gazing directly into the camera’s lens. These two photographs offer a stark contrast to the theatricality of his other work and would have been, perhaps, more appreciated if they were presented as part of a series of similar portraits.

The contemplative quality of Sultan’s work echoes in Mobeen Ansari’s photography. Most of Ansari’s photographs are portraits and he reveals that since he has a hearing impairment, he likes to communicate through photography. When asked how he approaches strangers to photograph them, Ansari shares, “I just smile” — a tactic that Ali Sultan also employs to put his subjectsat ease. Ansari originally studied fine arts and this lends his work a painterly quality. A dramatic photograph of an elderly woman, her body cloaked by an ochre chaddar, is reminiscent of paintings by Rembrandt and Vermeer to the extent that it looks staged. But Ansari shares that he simply chanced upon this woman while exploring the streets of Rawalpindi. His other portraits appear less dramatic with the subjects, a guard and a fisherman, gazing directly into the camera’s lens. These two photographs offer a stark contrast to the theatricality of his other work and would have been, perhaps, more appreciated if they were presented as part of a series of similar portraits.

The fourth photographer was Ali Khurshid who was recognised by Time magazine in 2006 as one of the People of the Year after they saw his photographs on Flickr. Khurshid’s work makes exuberant use of colour and he explains, “There are many different dimensions to the city and colour is one of them.” Hence, even in photographs of Karachi’s dusty streets, colourful flags and graffiti are his focus. In one photograph, brightly patterned umbrellas provide an unexpected jolt of energy to an otherwise grey and rainy Hunza landscape. Khurshid shares how he originally travelled to Hunza to photograph flowers but upon arrival he was greeted by rain and hail, which forced him to improvise.

With the advent of digital photography, the use of film cameras is slowly dying. It is therefore reassuring that photographers like Khurshid continue to use film, as he does, to capture a shot from the back of a rickshaw in which the softness of the image could probably not be captured with a digital camera.

These photographers not only have an eye for aesthetics but also the ability to improvise and adapt. Street photography does raise ethical questions about romanticising poverty and photographing people without their permission. Even renowned photographers such as Bruce Gilden and Dorothea Lange could not avoid controversy and such criticisms simply come with the territory. For the most part though, these photographers have steered clear of “poverty porn” and display sincere respect for the people they photograph.

This article was originally published in the December 2011 issue of Newsline under the headline “Street Art.”

More Newsline Articles on Photography:

Zehra Nabi is a graduate student in The Writing Seminars at the Johns Hopkins University. She previously worked at Newsline and The Express Tribune.