A Senator and a Statesman

By Marvi Sirmed | Newsbeat National | Published 7 years ago

During his three-year-long tenure as the Chairman, Senate, Senator Raza Rabbani truly reshaped the culture and elevated the stature of this august body. From March 2015 through March 2018, the Senate of Pakistan underwent landmark reforms, which in the process strengthened the institution manifold.

After the election for the Senate Chair in 2015, Senator Raza Rabbani took oath, and his immediate steps for institution-building in the Upper House made it clear that the next three years would bring about a new era of reformative change. Scores of reforms were introduced during his tenure, which were embraced by both the Treasury and the Opposition benches, with an open heart.

The first challenge that Chairman Rabbani had to confront was the long-standing tradition of interminable delays in House proceedings. Those media personnel covering parliamentary proceedings for several tenures would bear witness to the fact that before Rabbani, inevitably there would be a delay in the start of proceedings at the House, sometimes stretching to four hours. Rabbani changed this practice by setting a personal example, arriving and proceeding to conduct business on schedule. He also wrote a letter to all the incumbent Senators asking them to follow the rules of the House. As a result, within a few months of his taking over, the House started meeting on time, and the members were disciplined to abide by the rules while asking questions, especially with regard to issues of public importance on Points of Order — a parliamentary tool that had been hugely misused before.

Parliamentary business was streamlined by introducing various steps that minimised pending business. The Business Advisory Committee, comprising parliamentary leaders of all the parties represented in the Senate, which hitherto used to meet only at the beginning of the session, that too for only half-an-hour or so, and was dominated by the executive branch, became very effective. It started meeting more frequently, sometimes several times during House sessions, where members would meticulously discuss business to ensure that the Senate played an effective role in protecting the rights of the provinces.

When Chairman Rabbani took oath in 2015, there was a huge backlog: 180 cases pending before different committees. He requested the Senate Forum for Policy Research (SFPR) to devise an action plan for disposing off that business. The Forum executed the plan through the Business Advisory Committee, and by the end of 2017, the majority of the Senate’s backlog was done and dispensed with.

Previously, the Senate’s Standing Committees would take suo moto notice to examine the expenditure of the relevant ministry. During Rabbani’s term, however, Senate rules were amended to explicitly empower the committees to biannually examine budgetary allocations and expenditure. This considerably enhanced the Senate’s role in overseeing the economic policy and its execution.

The committee system is the backbone of parliament, which ensures that the Houses effectively perform their legislative, oversight and representation functions as envisaged by the constitution. Political scientists call the committees the “eyes and ears of the Parliament.” Paraphrasing Senator Sanaullah Baloch, over the years Senate committees in Pakistan had been systematically degraded and weakened to minimise their oversight role. Ever since they were established, following the promulgation of the constitution in 1973, the committee system had neither a professional support structure, nor any mechanisms for oversight, such as committee hearings.

However, after 2015, a number of initiatives were taken to improve the working of committees and their overall strength. For example, the Council of Chairs, a body provided by Senate rules, had never been active, but over the last three years it was not only activated, but also empowered by making sure its decisions were implemented in letter and spirit. Through its vigorous working, the Council was able to resolve many tricky issues, including the issue of low attendance of members in committee meetings. By the end of 2017, the attendance of members in different Senate committees was between 80 to 100 per cent.

Another landmark initiative under Chairman Rabbani was the establishment of the Committee on Delegated Legislation. This committee was entrusted with the task of scrutinising and reporting on whether the government was executing the powers to make rules, regulations and by-laws under different acts of parliament, as delegated by the parliament or the constitution in the time-frame allocated to it. This proved very useful in ensuring the implementation of many laws made by the parliament, the non-implementation of which – on account of a lack of rules and by-laws – used to previously go unnoticed.

Another major achievement of the Senate in the last three years was the introduction of Rule 265-A, whereby it is now incumbent upon the ministers to appear before the House every three months and report on all matters referred to by the House or recommended by the committees. This has made the ministries extremely cognisant of the need to ensure that the actionable recommendations of committees are duly implemented. Previously, the recommendations made by the committees used to go routinely unheeded by the ministries.

Today, not only is the Senate more open to civil society and the media, it also demonstrates a readiness to be more transparent in many aspects of its business. For example, today there is a far more user-friendly and interactive website than ever before, with the Senators’ attendance, and the House’s legislative and other business, including the questions asked during proceedings with answers, available on the website, and a bill tracking system made available to House members and the staff through intranet. Moreover, live telecasts of Senate proceedings are now mandatory.

In Rabbani’s tenure, in order to interact with citizens, the Senate not only used social media, but also initiated a public petition system, through which citizens raised many issues of public importance during the last three years. In order to engage youth, a promising programme of Senate interns was also initiated, through which dozens of young people enrolled during the Rabbani term.

Chairman Rabbani instituted many other reforms to make the executive responsible and accountable to the House, to encourage ministers to be prepared to answer members’ questions, and to make the Senate a ‘real House of Federation’ by ensuring that it played its role to strengthen provincial autonomy and fiscal federalism.

Ironically, although Raza Rabbani proved to be Pakistan’s best Chairman of the Senate to date, he was resented by some cabinet members. Meanwhile, his own party leader, Asif Zardari, told the media that Rabbani was not his choice for Chairman of the House because he was “too lenient on the government.” And pro-establishment elements within the parliament as well as outside it, lamented his role in getting the 18th Amendment passed, which gave provinces a semblance of autonomy. In a recent “off the record” briefing by a senior military official, he is reported to have expressed his utmost displeasure with Chairman Rabbani because of this amendment.

Rabbani’s fall from grace is Pakistan’s loss, and with him will probably go his professional and committed team within the Senate Secretariat. Amjad Pervez, for example, the Secretary of the Senate, who should be particularly applauded for his commitment to strengthening democratic norms and the institution-building of the Senate.

With the PPP and PTI-approved new Chairman of the House – the first from Balochistan – one might have still been hopeful. But according to reports, Sanjrani is ‘the establishment’s man.’

A Brief History of Pakistan’s Senate

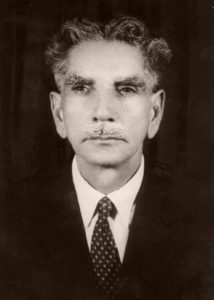

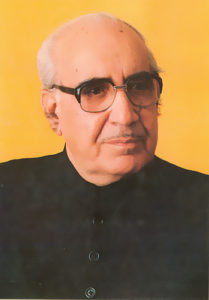

Unfortunately, over the past 45 years, ever since the Senate came into being with the adoption of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan 1973, the Senate has been barely performing the functions that come under its purview. Under its first Chairman, Senator Khan Habibullah Khan, the Senate was having the teething problems that are par for the course with a nascent house, when it was dissolved by the military dictator, General Zia-ul-Haq in 1977. The Senate was reactivated in 1985 and Ghulam Ishaq Khan took oath as the Chair of the House. During his tenure, this body remained a rubber-stamping centre which abstained from exercising its independent powers, merely approving whatever was desired by the all-powerful executive branch at that time.

Khan Habibullah Khan

Ghulam Ishaq Khan

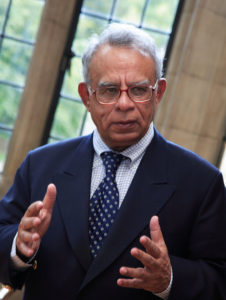

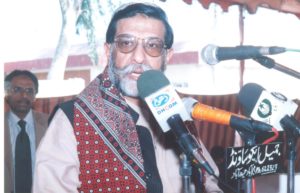

It was almost the same case during the time of Senator Wasim Sajjad, the third Chairman of the Senate. Apart from the increase in the standing committees, a disproportionate increase in the size of the secretariat and a few changes in the Senate rules to streamline the House’s business, nothing substantive was visible during Sajjad’s spell of almost 11 years as Chair, from 1988 to 1999. And then the country’s fourth military leader, Gen. Pervez Musharraf, once again dissolved this House in 2003. After the Senate was reconstituted following the elections, Senator Mohammed Mian Soomro took oath as the Chair and remained there till 2009, when Senator Farooq Naek succeeded him as the fifth Chair of the house, staying there until 2012.

Under Senator Soomro, the Senate secretariat increased in size by leaps and bounds once again, the numbers swelling mostly on an ad hoc basis, without any human resource management policy in force. It was during his chairpersonship that multilateral organisations like the UNDP conducted a comprehensive needs assessment of the House. There was, however, zero initiative and poor technical capacity within the Senate to critically assess the offers of assistance or articulate its own priorities. Ergo, most of the international assistance was wasted, because of the lack of ownership of the assistance proposals.

Wasim Sajjad

Senator Naek’s contribution to the Senate was more positive than his predecessors. He deployed existing human resources in relevant jobs instead of hiring new people without job descriptions. He also started paying more attention to assessing international assistance proposals alongside initiating the process of prioritising the Senate reforms agenda. A landmark achievement of the Parliament during those years was the establishment of the Pakistan Institute of Parliamentary Services (PIPS) – a joint institution under the elected houses – for providing different services to the elected representatives at the federal and the provincial levels, in addition to offering tailor-made training courses for the staff of the secretariats of parliament and the provincial assemblies. When his term ended in 2012, the sixth Chairman of the Senate, Senator Nayyer Hussain Bokhari took oath.

Mohammad Mian Soomro

The Bokhari tenure was marked by the policy inertia peculiar to the democratic institutions of Pakistan. A ‘Five Year Strategic Plan’ was produced, which largely remained a donor-driven initiative rather than a parliament-owned, parliament-led enterprise. This was why, apart from some piecemeal steps here and there, the Senate secretariat did not take it seriously enough to implement it in totality.

Farooq Naek

Several amendments to the Senate Rules, were however, made during Bokhari’s tenure. But it was noted by parliament-watchers with great concern that neither was the Senate able to challenge the domination of the executive branch, nor could it demonstrate any propensity to reform itself as an efficient and professional centre of excellence that would serve as a legislative chamber in a majority-constrained federal state. However, the establishment of the Senate’s own think-tank, the Senate Forum for Policy Research (SFPR) was a landmark development.

Nayyer Hussain Bukhari

The Forum provided a platform to create and enhance the Senate’s in-house capacities for legislative and policy research, as well as legislative drafting. Legislative drafting, it may be noted, has vanished from the country’s major law institutes as an academic discipline, which is the main reason for an extremely short supply of draftspersons available for the public sector institutions. When Bokhari took the Chair, none of the legislative houses, had a dedicated legislative draftsperson. The legislative houses in Pakistan usually requested the law ministries (federal and provincial) to provide the service through its very limited pool of draftspersons. Now, because of the SFPR, it has become possible for the Senate to generate its own pool of legislative draftspersons – a great milestone.