Cover Story: Never Say Die

By Ayaz Amir | Cover Story | Published 9 years ago

Idolised by many, not taken seriously by others, in the political wilderness for a long time, trying to build up a party from scratch, for years trudging from one small town to another without much to show for the effort…and then, almost out of the blue, striking stardust in a famous jalsa in Lahore in 2011. This was Imran Khan’s rebirth, his second coming as a politician. Where he and his party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, stand today, dates from that happening.

Our cricketing hero-turned-politician thought power was finally within his grasp…if not at his feet, waiting to be picked up. He was probably the hottest item on the sporting field that Pakistan has had, and he had built an imposing cancer hospital in Lahore. But politics seemed not to be his currency and his party, the Tehreek, was for pundits and cynics alike, a bit of a joke.

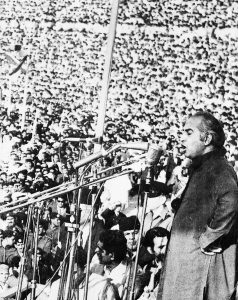

And now after this long trek across the sands, where a lesser man would have given up and called a plague on all the houses of politics, he seemed to have made it, the crowds finally responding to him, his message — a bit vague, not spelt out all that clearly, lacking the flair and imagery of the PPP manifesto when Zulfikar Ali Bhutto founded the party in 1967, but revolving around the words “corruption” and “change” — at last finding resonance.

And there was music at his rallies and the young of both sexes came to them turning his election campaign into the kind of political theatre not seen across Punjab, the main battleground in the election, since Bhutto’s heyday all those years ago. From the lights and the theatrics and the crowd came the mood and the glow of certainty that the coming elections in 2013 were his to win and that he was about to sweep them.

At an election rally he had fallen from a crane and hurt himself badly. He was in hospital when the results came in, and when they did not bear out his blown-up expectations, it is not hard to imagine his bitter disappointment. Devastation would be the more apt word.

A man less determined, less persuaded of his greatness — he believes he is marked for greatness — would have been shattered, tempted to give up. But he picked up the pieces from there and making election rigging his battle cry, announced a march on Islamabad in August 2014.

Did someone whisper from the shadows that he had only to knock at the gates of the capital and things would happen and the ‘third force’ — for much of Pakistan’s history the ultimate decider of power and politics — would come marching in and put an end to the astonishing run of luck of the House of Sharif, in power longer than anyone else in Pakistan’s strife-torn history? This is what many people still think, that Imran Khan and his partner-in-agitation, the mercurial Allama Tahir-ul-Qadri, were acting out a script written by others.

Nawaz Sharif’s government was rocked by the marches — and the stony looks of the army command which allowed the government to be rocked and did not come rushing to its rescue — but the expected intervention never came. And Imran Khan was left trying out his skills in oratory — he has undeniably become a better speaker over the years — atop a container in D Chowk in the Blue Area of Islamabad, such being our felicity with names. The crowds would come and the atmosphere would be festive every evening… but that was about it. The whole thing petered out and Imran Khan, from an Olympian high, plummeted to a political abyss. The marches and sit-ins, exhilarating while they lasted, left a bitter hangover.

But, and anyone would have to hand it to the man, Imran is still there, refusing to go away, on the attack all the time, talking about corruption and accountability endlessly. The House of Sharif remains in power, but Imran has become their biggest nemesis, and their principal challenger in what just a few years ago was their uncontested domain of Punjab. The party of Bhutto was gone, a victim not so much of external circumstances as of Zardari-induced political suicide. The resulting vacuum was filled by Imran and his PTI and for all his failings and missteps this counts as his biggest political achievement — becoming the principal counterweight to the House of Sharif.

In the 1997 election, which Nawaz Sharif’s party, the PML-N, swept, the recently launched PTI’s performance invited jokes and ridicule. It was much the same in the 2008 elections which Imran, for abstruse reasons, boycotted. But no one can dismiss the PTI today. When the 2018 elections come, in every constituency of Punjab, the powerhouse of Pakistani politics, the contest will be between the House of Sharif and Imran’s candidates. That’s a measure of his political achievement, having lifted his party from the depths — and it was in the depths for a long time — and turning it into a major political force.

All other parties, including the PPP, have become bit players or rather  regional players. On the national scene there is the PML-N in power at the centre and Punjab, and the national opposition now is represented by Imran and the PTI. To a large extent this is less because of anything to do with message or manifesto, and more a reflection of determination — the power of will — and strength of personality.

regional players. On the national scene there is the PML-N in power at the centre and Punjab, and the national opposition now is represented by Imran and the PTI. To a large extent this is less because of anything to do with message or manifesto, and more a reflection of determination — the power of will — and strength of personality.

Imran has had to drink from the cup of rejection and humiliation. As already pointed out, a lesser man would have raised his hands in despair and given up. Or would have turned fulltime to hospitals and philanthropy — and girl-hunting, for, as the daughters of Venus could testify, and to the envy of other men, he is still a great draw as far as women are concerned. Playboy of the eastern world…that’s a choice he still has. But he’s soldiered on and on and against the odds, and against the established patterns of Pakistani politics, has crafted a political persona for himself.

The Sharifs don’t like General Raheel Sharif — his elevation in the public eye casts a shadow over them. And they don’t like, or they rather fear, Imran Khan. In various forms they have ruled Punjab for more than three decades…and given the topsy-turvy nature of Pakistani politics, this is a long time. They have created a structure, almost a system, of power and patronage which is not easy to break or challenge. But Imran with not much of a team, and with little organisation, the PTI being a notoriously disorganised party with a penchant for splits and factionalism, has managed to shake their confidence.

The Sharifs have already begun campaigning for the 2018 elections. All this tape-cutting of new projects is part of this campaign. But when they make their calculations about those elections, when they look over their shoulders, they have no other A, B and C in mind except Imran Khan. He is the spectre at their table of victory. The PML-N may be winning most by-elections, but in all the contests recently held, the PTI has been close by, at times too close for comfort, snapping at the PML-N’s heels. The PML-N can’t be too happy at this outcome.

There is one difference between the Sharifs and Imran Khan that has to be kept in mind. The Sharifs were injected with hormones and put on a pedestal by the Zia regime which was looking for counterweights to the PPP, the party of Bhutto representing Gen. Zia’s biggest political problem. Zia had hanged Bhutto but the latter’s party, the PPP, was refusing to be crushed, turning into Gen. Zia’s biggest nightmare. In the quest to weigh down the PPP, an alternative set of politicians was created and boosted up, chief among them the Sharifs. To Nawaz Sharif’s credit, however, once hoisted on that pedestal by the regime, he sprouted wings of his own and became a genuine political leader in his own right.

Imran Khan entered the political arena on his own, his being a lonely and, in the initial years, a thankless journey. Against the odds he persevered, braving for the most part an unbroken run of failure and misfortune. If he has survived and still emerged as principal alternative to the Sharifs, this is a tribute to his courage and determination.

Part of his misfortune has lain in an unfair comparison in the public mind between him and Bhutto. Bhutto’s was not so much an ascent as a race to the top. Within three years of its formation, the PPP like a hurricane had swept all before it in Punjab and Sindh in the 1970 elections. There were people expecting Imran to do the same thing. But his circumstances were different. The old order represented by the Ayub regime was on the verge of collapse when Bhutto entered the ring. The old parties were dead, the old political leadership not coming to within an ounce of Bhutto’s appeal and charisma.

When Imran entered the political arena, the political order shaped by the agencies and the army, and embodied by the Sharifs, was not merely alive but going strong. Today’s Nawaz Sharif is an aging and slightly obsolescent political figure, commanding an impressive parliamentary majority but slightly breathless and tainted by scandal — the Panama Leaks among others — and the long shadow cast by Gen. Raheel.

But back then Nawaz was at the peak of his appeal and he, rather than anyone else, represented a force for change. Imran Khan looked and sounded very much like an irrelevance — a cricketing hero who had stepped into the wrong stadium.

If we keep in mind those unpromising beginnings then his journey becomes all the more remarkable. Moreover, while he has his strengths — courage and persistence, qualities which Bhutto had too — he lacks Bhutto’s way with words, the flair for oratory that could sway any crowd. He has improved as a speaker but he still doesn’t light a fire in your belly…although the young root for him, men and women alike. And he has strength of character and is clearly a leader — qualities that have brought him this far.

If we keep in mind those unpromising beginnings then his journey becomes all the more remarkable. Moreover, while he has his strengths — courage and persistence, qualities which Bhutto had too — he lacks Bhutto’s way with words, the flair for oratory that could sway any crowd. He has improved as a speaker but he still doesn’t light a fire in your belly…although the young root for him, men and women alike. And he has strength of character and is clearly a leader — qualities that have brought him this far.

But his greatest weakness, his blind spot, must also be noted. He misread the whole terrorism thing completely, remaining firmly tied to the old clichés about the power of dialogue and reaching out to the Taliban long after the utter futility and even outright danger of this approach had become all too apparent. Nawaz Sharif too was weak on terrorism and that should have been the time for Imran Khan to sound the alarm and much like Churchill at the time of Hitler’s rise to power and beyond, to call the nation’s attention to the menace of radical Islamism.

Even after the attack on the Army Public School in Peshawar, when the political parties and the Nawaz Sharif government were forced to come out of their trance regarding the Taliban, Imran Khan just went along with the tide instead of assuming a leadership role and telling the nation that it was time to take a fresh start and abandon the old ways. Just as Hillary Clinton is still haunted by her support for the Iraq war, questions will be asked about Imran’s less-than-sure, even indulgent stance on the Taliban threat to Pakistan.

But the future beckons and Imran Khan is right there in the lists. If everything remains in place — meaning thereby that the constitutional deck is not disturbed and elections are held on schedule — the fight in Punjab, as already stated, will be between him and the Sharifs. This is a measure of where Imran, for all his many slipups and missteps, has managed to bring his party.