War of Words

By I. A. Rehman | Newsbeat International | Published 8 years ago

For more than 10 days I have been watching this ugly charade outside the highest seat of justice in the country.

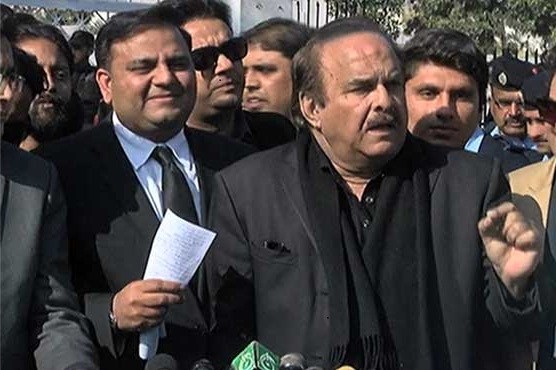

Every morning there is a stream of normal-looking political dignitaries, each eager to enter the Supreme Court building earlier than the other. Many of them are known as national level politicians or, to recall a pre-independence way of grading politicians, all-Pakistan leaders. Some of them have been elected by thousands of people to represent them. Most of them display grey hair though without offering any indication as to what lies underneath.

They seem happy, with broad smiles on their duly spruced up faces. Now and then they wave the victory sign or greet people out there. Later in the day, many of them rush to improvised stands to demonstrate how much gall they can spit out per second. Assuming the air of sages, honest and brave, they go flat out to prove how ugly, how devious, corrupt and foolish their political rivals are.

Someone is denounced as a thief and dacoit, another one painted as the devil incarnate. So and so is a cheat. So and so has been blinded by avarice. This man is so busy gathering his loot that he cannot see the suffering of his fellow beings. That man is sabotaging the country’s progress and thus adding to the people’s suffering.

With their faces drawn taut and froth lining their lips, they thunder on and on and bury their rivals under the choicest expletives. Laurels are claimed for unbridled vulgarity. Unfortunately the roots of this obscenity lie in Pakistan’s political history. Wasn’t a political rival called a dog in the early days of independence? And, four decades or so ago, didn’t we hear a political leader being called a rat and another a potato, good enough only to be put on a spike. And didn’t we see doctored photographs of women politicians in the 1980s, circulated to deprive them of voter support?

These efforts at downing political rivals denoted a break from the pre-independence tradition of attacking political opponents for their policies and avoiding attacks on personalities. Surely, there were exceptions, like a leader being declared a “kafir” or another being dismissed as a mere “show boy” or somebody would borrow from the British debates and call someone a “quisling” or “toady.” But such fare was only for the consumption of the juvenile fringe.

It was the founders of authoritarianism in Pakistan, who developed demonisation of politicians into one of their principal instruments to capture power and to keep the democrats at bay.

This began with Iskander Mirza who, while sacking democracy in favour of martial law, blamed the politicians for the mess for which he and his cohorts (such as Ghulam Mohammad) were largely responsible. He even told the deposed politicians to leave the country while the going was good. The politicians stayed on, while he himself was exiled by the heir apparent of his own choice.

Ayub Khan continued with the demonisation of politicians, especially those who dared to swear by democracy. Not content with banishing leading politicians into the wilderness for about nine years, he went on to denounce democracy as something incompatible with the genius of the Pakistani people, discontinued the method of choosing members of legislatures through direct elections, and created a system of party-less parliament and a cabinet of ministers who owed no allegiance to any political party and were not members of parliament. He failed, and in despair destroyed the edifice he had himself built with great fanfare.

Along came Zia-ul-Haq and he thought he could succeed where Ayub had failed. He recognised only the politicians who did not belong to any party. He too failed and had to axe his hand-picked front man — Prime Minister Muhammad Khan Junejo.

Pervez Musharraf carved a slightly different path. He assumed the state was a business enterprise, so he became its Chief Executive Officer. While his predecessors tried to do politics by outlawing political parties, he conceived a state without an independent judicial pillar. Ultimately, he too had to find safety in the lap of some much maligned politicians.

Democratic politics has survived demonisation of politicians by extra-political adventurers but it is unlikely to survive the game of mutual demonisation the present gladiators are playing. The political issues under debate can be resolved without the kind of mudslinging that is going on. The conduct of the invective-driven brigades suggests that their claim of faith in the court whose space they abuse is only skin deep.

Why can’t they realise that they are discrediting not only their rivals but themselves as well, and politics in general. Even if half of what the contending parties accuse each other of is believed to be true, the people are left almost without a choice. That can only result in citizens’ further alienation from politics and the system of representative government.

Meanwhile, the people are being bombarded with tales of development and economic turnaround discovered by the world’s statesmen and business tycoons arriving from Davos. Does the affair sound like the decade of development the Ayub regime urged the people to celebrate in 1968-69, on empty pockets and half-filled stomachs?

Those who are in power and those who want to come to power appear to be too self-centred to inform the people of the crisis the agricultural community faces, or the plight of labour, especially in the informal sector, or of the dangers the state is courting by suppressing civil society and recruiting militant clerics to extinguish the right to freedom of expression. There are more Tayyabas in Pakistan than the Supreme Court can take care of. And why should the court go on doing the work of a moribund administration?

And as I witness the daily charade, I wonder whether the condition of the Pakistani people can be more aptly summed up than by what Thomas Hobbes said in the 17th century: “No arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Mr. I.A. Rehman is a writer and activist living in Pakistan. He is the secretary general of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan Secretariat.