Interview: Unver Shafi Khan

By Saquib Hanif | Interview | Published 8 years ago

Back in 1999, in a rare snatch of conversation uninflected by his incisive but often highly critical outlook, noted art critic Dr. Akbar Naqvi described the then 38-year-old Unver Shafi Khan as a “painter’s painter.”

Asked to explain what he meant, Dr. Naqvi went on to highlight Unver’s formalist skill evident in the visual eloquence of his wristy line, delineation of form and colour application as well as his absolute command over detail and gesture.

More importantly, he added, a painter’s painter is not manacled by successive moments of taste and births his own pictorial syntax as dictated by his artistic imperatives. So it is, Dr. Naqvi concluded, that the work of a painter’s painter would invariably endure and invoke contemplation irrespective of time and space.

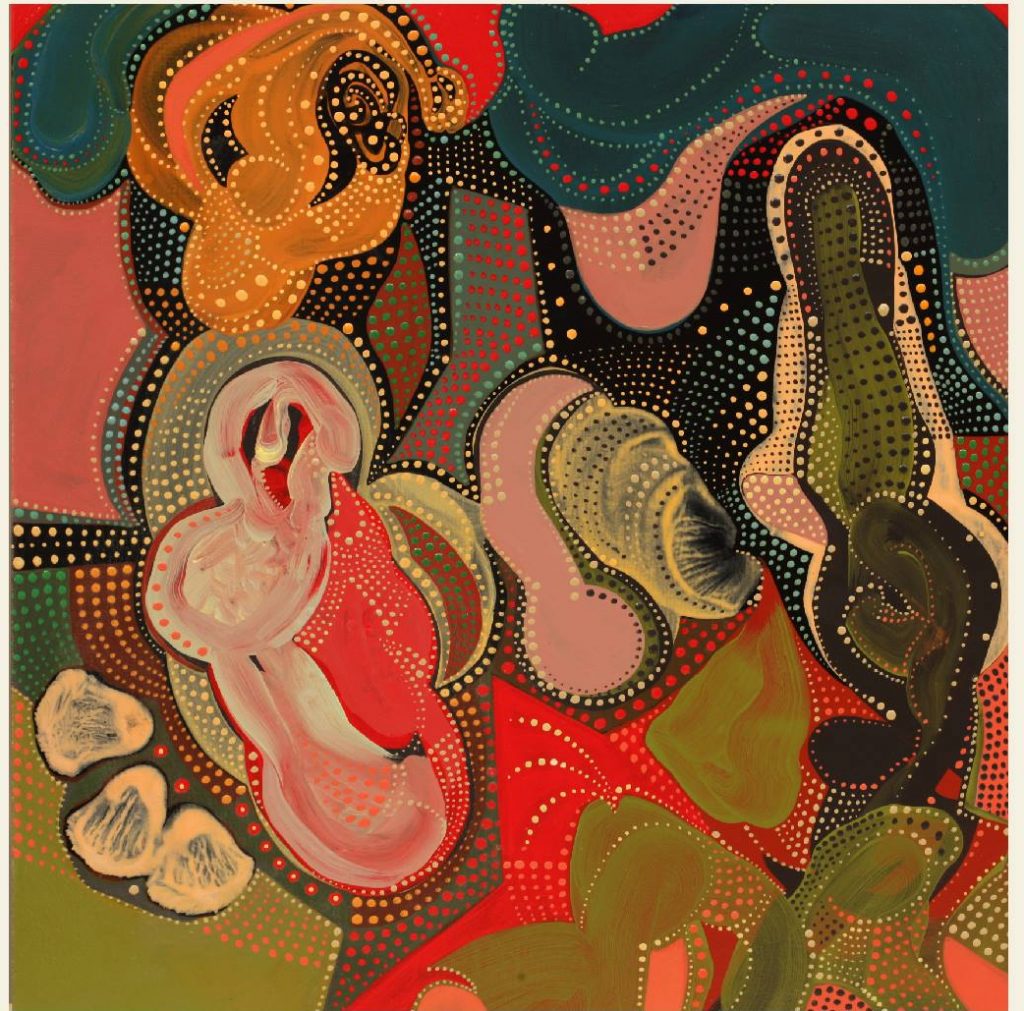

Such were the thoughts coursing through my head as I saw the now 55-year-old Unver’s new work slated for a show opening at Koel Gallery on January 18. It was all there: the shapeshifting form in Jules Verne, the saturation of colour in Desi Wedding, the fluent shifts in detail in In the Court of the Romantic, the varied brushwork in Afternoon at Las Ventas No. 2, the ever-so-slight gradations of camellia pink in William Tell, the apple is your head, the marvellous treacle of left-to-right strokes in Urdu Poetry. And besides being a feast for the eyes, the work bid you to stop and wonder what it was all about. Over to Unver…

Can you retrace the journey of the Fabulist series? How and when did it all begin?

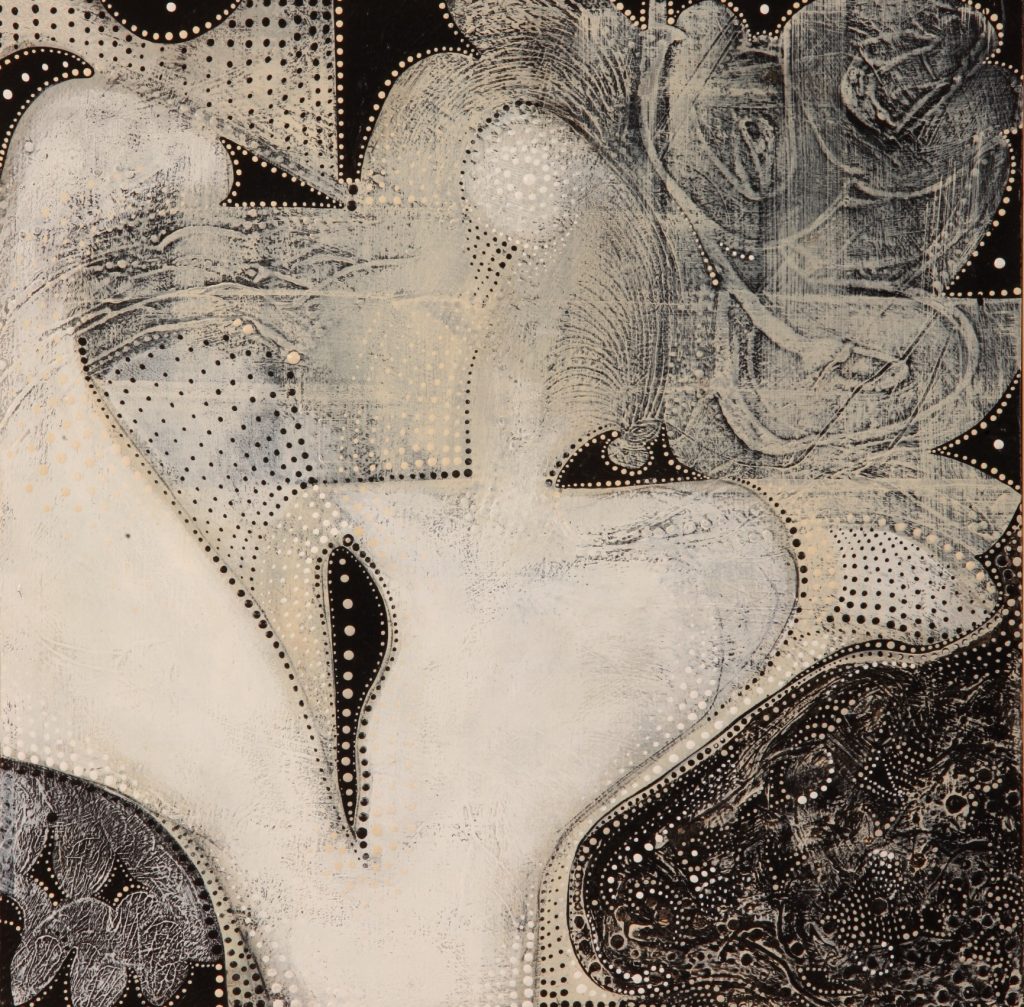

The genesis of the Fabulist series goes back all the way to the early pen and inks I made while at Kenyon College, USA between 1980 and 1984. They have in common the pixel/dot/ bindi point marks along with the doodle-like figural references.

The pen and inks employed an assortment of tools — reed pens, colour pencils, brushes, draughting pens, quills and mechanised erasers — required for the kind of mark-making I was interested in at the time, which was very gestural and automatic, leavening the psyche for images.

The pen and inks also involved the use of watercolour and were incredibly detailed and mostly executed on fine quality Sennelier paper no larger than 8.5”x11” in size.

In many ways, I was revisiting the miniature without the formal training in its technique.

Several critics see the Fabulist series as a “breather” from your large oils, implying perhaps that the paintings falling under the rubric are less “serious,” even “decorative.” Do you agree?

In no manner or form are the Fabulist paintings any less important than the oils. That’s like saying the early pen and inks are less important.

As a painter, I have explored and continue to explore different mediums and all the paintings coming out of my studio have their own special relevance in the overall body of my work. A corollary of a change in medium is a change in subject matter: the transcendent quality of oil pigment is so different to the flat rich plasticity of acrylic paint, yet one can feast in equal measure on their varied palette.

The work exhibited last month at Koel Gallery is described as being “in the Fabulist style.” Do you seek to distinguish this body of work from the series in general by calling it as such? If so, what has changed?

In the late 1990s, the pen and inks went from being on paper to canvas and from ink and watercolour to acrylic. It was in 2002 that I titled the first of these paintings as the ‘Fabulist Series’ and started numbering them. The size of these paintings went from 6”x6” to 15”x15.” And the numbered Fabulist series ran to about 390 over a 10-year period.

Around 2010, I stopped numbering the paintings as I wanted to play with specific titles for this work. I now add to the title “in the Fabulist style” in parentheses as a reference to when this imagery originated.

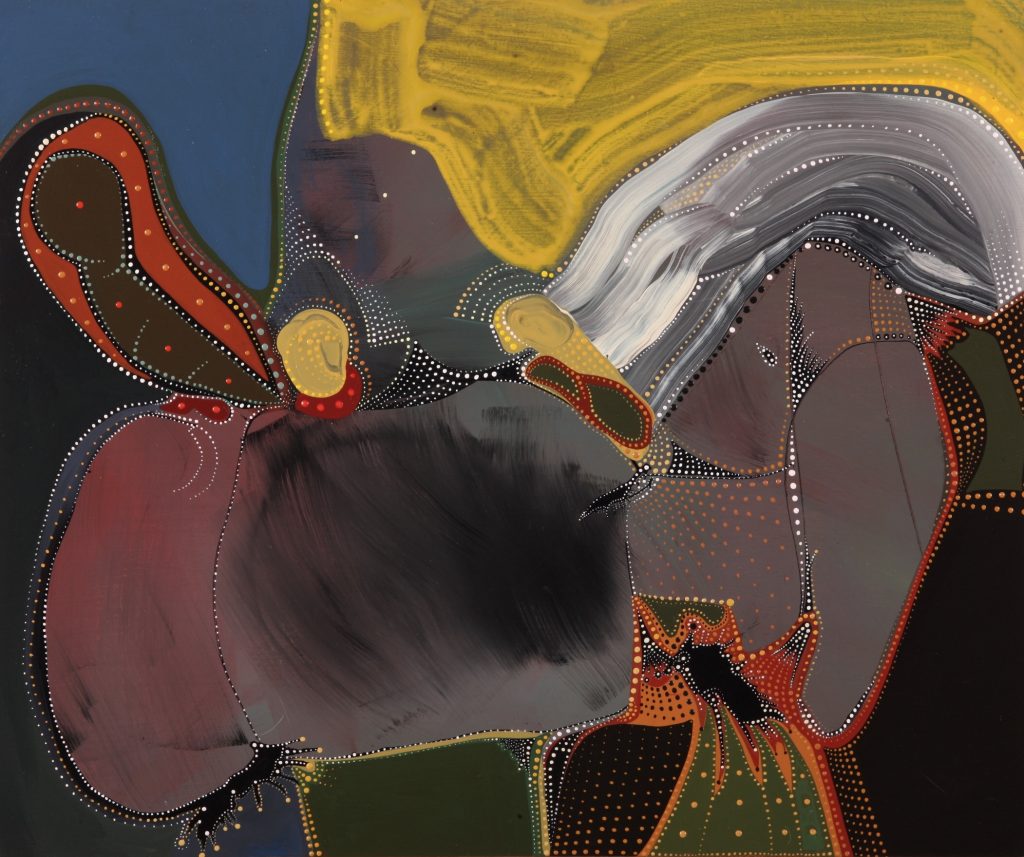

Going by the paintings in the Koel Gallery show, there is, in fact, a distinct sense of breaking new ground as is clearly evident in transitional works such as Urdu Poetry and Afternoon at Las Ventas No. 2. The scale is bigger, there is a lot of texture just as the strokes or passages of paint are far more painterly. Are you aware of this change in direction?

Yes, I am acutely aware of a subtle shift in how this work is now being executed. The paintings in the Koel show are selected over an 18-month period (June 2015-December 2016) and are intensely textured and also larger in size. I had previously thought that going beyond a 15”x15” size, the work would lose its jewel-like intensity, but this batch of paintings has revealed otherwise. The vocabulary of these paintings has changed significantly yet the use of the dots is still there. I intend to expand the scale further and see how this pushes away even more from what I have been doing.

Where do you see yourself going from here?

I have 10 very large canvases stretched and ready and about a dozen small ones. I am showing two of the largest-ever oil paintings for the Karachi Biennale. And Koel is hosting a show of my oil paintings alongside the Biennale.

Despite living and working in Karachi, you haven’t exhibited in the city since your last show at Canvas Gallery back in 2004. Can you cite any particular reason for the hiatus, especially as you have been painting consistently throughout this time?

I was actively showing paintings and pen and inks every two years at the Alhamra in Lahore, Rohtas in Islamabad and Indus Gallery, Ziggurat, Chawkandi Art and Canvas Gallery in Karachi, besides assorted solo and group shows both at local and international venues.

After the Canvas show in 2004, however, I felt the energy required to show was a hindrance and wanted to focus more deeply on developing my own vocabulary. I needed a break from the public eye and decided to let those interested in my work find me instead.

Does the fact that you are one of the few formalist painters working today have anything to do with reduced visibility in the gallery circuit?

In many ways, my approach underwent a basic change. Maybe being a formalist painter had something to do with this. I wanted a more intimate and personal connection with those who valued my work. Less was suddenly more. But in the past couple of years, I have wanted to show my work in Karachi, the city I have lived and worked in since 1984.

A lot of contemporary art practice in Pakistan is self-consciously ‘political’ and, as such, deemed relevant. Against this scenario, your work has been considered divorced from the time and space in which you are working? What determines ‘relevance’?

A lot of contemporary art practice in Pakistan and what we are exporting is made with what galleries and institutions in the West can plug as being relevant politically and socially. For me, every artist is compelled to explore his/her own truth. For me, painting is about probity, the inner workings of how we see. If I can thereby make people think and wonder, my job is done. This is how I approach my work. I do not paint thinking I am Pakistani or South Asian as before that my lot were Indian, before that Afghan, before that Central Asian. I am all of the above and yet irrevocably a contemporary Pakistani painter and a citizen of the world — my passport notwithstanding.

You describe yourself as a painter rather than an artist. Do you see the two as being different in terms of inclination and aspiration?

I have for the past few years been making a point to everyone that I am a contemporary painter and not an artist for the simple reason that everyone is an artist today.

As a painter I have enjoyed the mental and physical act of painting through some traditional and some very untraditional means, tools and techniques to forge my own vocabulary. It has been a journey of many years as anyone involved with craft and technique will understand.