No Burden of Proof

By Afsheen Ahmed | Bookmark | Published 8 years ago

Marriage is a difficult terrain to negotiate in any society or culture but, on reading this study, it would seem, that  perhaps nowhere is it more difficult or more violent or more complicated than in Upper Sindh.

perhaps nowhere is it more difficult or more violent or more complicated than in Upper Sindh.

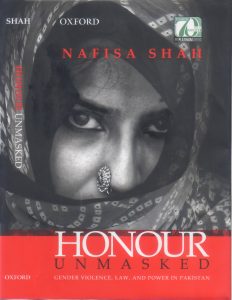

The author, Nafisa Shah — former journalist, academic, politician, ex-Nazim of Khairpur in Upper Sindh (2001-2004), and, currently, a member of the National Assembly of Pakistan, representing the Peoples Party — launched her meticulously researched book — Honour Unmasked: Gender Violence, Law and Power in Pakistan — at the end of December 2016 in Karachi, with much ado, and a huge turnout from the political and the civil society sphere.

The genesis of this book was a cover story that Shah, then a cub reporter, did for Newsline in January 1993 (Karo-Kari: Ritual killings in the name of honour). It was the first ever comprehensive report on karo-kari killings — men and women who are killed on suspicion or accusations of adultery — in Upper Sindh. The story sent shockwaves through the country, and beyond. Shockwaves that continue to reverberate in ongoing debates in the media, in civil society forums and in the legislatures. But that is another story.

Shah moved away from journalism to academia, and went on to research the subject more dispassionately, and in greater detail, in Upper Sindh — the land of her birth and upbringing. What emerges, despite being couched in formal phrasing, is a chilling tale. Of inter and intra family and tribal feuds, some that last decades, many still ongoing. And mostly all this within closely related blood kin, meshed in a web of marriages and relationships.

While Upper Sindh reports the highest number of karo-kari deaths — about 200 men, women and children killed each year — nearly a quarter of such reported deaths from all over Pakistan, the study findings would probably apply all over Pakistan. However, Shah posits that it is wrong to say that women alone are victims, as nearly a third of the recorded killings are of men and, even though those committing the murders may be men, often women “collude in these acts of violence.”

So, what exactly is meant by karo-kari? Shah has defined it as a “complex system of sexual/social sanction that is considered to be a part of the moral ideology of honour.” In Upper Sindh, women signify ghairat or honour, which is violated if they are perceived as having sexual relations with men other than their husbands. “The practice of karo-kari is a part of the local norms and practices.” Karo means black man and kari means black woman, the colour symbolic of sin in various regions of Pakistan. In one of the most telling quotes on the subject, a mother, who had participated in her daughter’s killing says, “It is better to chop off the rotten finger.”

It all seems to revolve around girls and women and marriage and sang. “Marriages,” as Shah explains, “ are political sites, where power is constituted and negotiated. Sang is a term meaning ‘relationship’, but implies the giving and taking of women in marriage — “‘sangawatti’ or exchange marriage, an ideology that is strongly valued.” So strongly, that should any side feel that they have been deprived of their ‘due’ sang, this is a good enough basis for bloody, relentless, internecine strife.

Shah had a difficult road to travel in doing this study. Although a Syed, born in the region, speaking the language, familiar with the milieu the study was being conducted in, she concedes even she had difficulty getting accurate information and that in her role as Nazim, “I lived the limitation of power every day as I experienced how people manipulated power.”

Shah’s findings confirm that karo-kari is frequently used as a cover-up for a multitude of sins — including domestic violence. Another reason could be that it is acha dhanda (good business). Is it because, if the man is allowed to live, he or his family or tribe, will cough up fines for ‘honour damage’?

Shah says that “Karo-kari can be seen as a transaction… Many of the accusations are pre-empted and designed with the eventual compensation in mind — compensation that will flow from the accused black man to the accuser, to compensate the man (the accuser) who has killed or expelled a woman.”

Rates of compensation have been given in detail, ranging from Rs 100,000 — 600,000. Currently, the official rate (37,000 grams of silver) is the highest, at Rs 750,000 per murder compensation. These compensations apparently run into millions of rupees daily. Many of the accusations are directly tied to claims over land, and forcing the other sides’ hand. It is cruel, it is mercenary, it is a fact of life.

And, yet, as Shah points out repeatedly in her study, these customs, rasms, riwaaj, are not conducted outside the ambit of the law, but, from British colonial times, these, in a process like osmosis, have been absorbed into laws.

Records going back to the early 19th century show that Charles Napier, the controversial ‘hanging conqueror’ of Sindh, appalled by the numbers of women killed, proclaimed in August 1844 that, henceforth, if anyone killed his wife, the matter would be investigated and the offender punished. However, interestingly enough, under his watch, no husband was hanged for the offence, other relatives were. Napier, too, “was not free of ambiguities in working out who was the guiltier of the two, the adulterer or the killer, and he often sympathised with the man who killed his wife.” The leniency of the British towards honour crimes, thus, strengthened this custom and transformed it into a legal defence.

From then, until the 1990s (probably after the earth-shaking Newsline Karo-Kari story broke), the killing of women was not seen as a separate category of crime. The British practice of giving local chiefs judicial authority to mediate in murders, incorporating the provision of ‘grave and sudden provocation’ which resulted in milder punishments, were both carried over to the newly independent state in the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC) XLV of 1860.

Then, in 1961, Ayub Khan passed the landmark Muslim Family Laws Ordinance (MFLO), which introduced a uniform code for marriage and made registration of marriage mandatory. It also recognised a woman’s right to divorce. The MFLO gave legal cover to adult men and women to contract marriages of their choice.

General Zia added a regressive twist with his promulgation of the Hudood laws (qisas and diyat). The qisas and diyat laws made two conceptual changes to the earlier homicide law. While, previously, murder was a crime against the state and could not be compromised (compounded) in any way, under the new dispensation, “the role of the state changed from a deterrent to a mediator between the accused and the victim…and homicide a private offence committed against the victim’s heirs, defined as wali, and not against the state as is the case in western jurisprudence.” However, despite heated objections from various quarters, the provisions of qisas and diyat became part of the PPC and the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) by parliamentary approval in 1997.

There are many reasons put forth very frankly, and with great courage, by Nafisa Shah, where the whole issue of karo-kari as a social phenomenom is seen from a hitherto unacknowledged perspective. She talks of how, within farming communities, informal or formal “offers of women’s sexual services may be a part of the protection system…religiously ranked families, or landowning families with powers of protection may be provided with women for sex and domestic service combined.” Some kidnapping and elopement charges, she says, are probably cover-ups for prostitution. The threat of punishment does not, apparently, stop these parallel relationships “and not everyone who has an adulterous relationship is labelled and killed.”

Although the whole book was a revelation, I found Part III — Normalizing Violence: The Everyday World of Upper Sindh, perhaps the most intriguing.

How does ‘normal’ life resume after brutal bloodletting, mostly between close kin?

Like the violence itself, the resulting faislo, Shah says, takes place within the state law and bureaucratic structure. The disputants, who are extremely litigious in Upper Sindh, will file cases, call on the police and other state apparatus to put pressure on the other side to come to the mediation table, which is then undertaken by mediators, who may be judges or lawyers, but could also include local sardars and others who have the power to enforce compliance on agreed terms.

Shah points out that of the 1482 cases reported over 10 years that she researched the issue, where more than 1600 men and women died, only 47, or a little over 3 per cent of the cases, reached conviction. Even this number would go down as most “conviction cases that go into appeal to the High court are reversed and bailed.”

Shah asserts that the low rate of convictions is not due to problems in the law, but in fact while operating within it. “The legal empowerment of the family to pardon crime allows acquittal through the law, so that, while one family member performs the act of violence, another condones it…the joint system of marriages, collective ownership of land, local systems of power and mediations, lead to family members pardoning the perpetrators within the family.” Shah has included some detailed and fascinating case studies that are mind-boggling in the complexity and web of marital relationships, and how these conflicts play out.

It is, as stated in the book, mostly “self-help justice.” Given that the official judicial process can take decades, and informal mediations are encouraged, when both sides have had enough they agree to a settlement. However, as the case studies show, it is only when ‘equivalency’ has been achieved in terms of mutual loss of life, limbs, property, that mediation will be considered. More importantly, only then will agreements be upheld. Settlements may involve cash or in kind exchange, preferably of land, but the most in demand is that a girl/woman be given in marriage, to the aggrieved party, as compensation.

Meantime, while the case is in court, elaborate ceremonies of peacemaking are organised, and in a karo–kari case, where the karo has not been killed, his family, led mostly by women, and other influentials, will go in a mairh minth kafila (caravan of peace), carrying the Quran over their heads, to ask for forgiveness from the aggrieved party, to pressurise and to implore a settlement. “In the local honour system, it is obligatory to forgive when women come to your door.”

Regardless of the number of murders, there will eventually have to be a settlement, usually decided by a local jirga of men only. “In karo-kari cases, the question of proof is a non-issue; it is the action itself that is the proof of guilt or innocence.” If a woman is killed or expelled by her family that is proof enough. The woman’s narrative is irrelevant. According to Ahmed Ali Pitafi, head of the Pitafi Baloch in Ghotki, “The good thing (!) among the Pitafi is that they always do double murders. Both karo and kari are killed, often together.” So no settlement is needed.

At the end of the karo-kari journey, the irony is that after the murder, after the charge and the trial, after the ceremonies of mairh minth, followed by mediation and kheerkhandr (becoming like milk and sugar), fines are paid, and enemies join together in a meal. Statements are withdrawn from courts, a razinama is drawn up, followed by acquittals. And, sometimes, even a marriage between feuding families, as a finishing touch. A masterly utilisation of law and custom — to everyone’s satisfaction. Till the next round.

The book offers no comforting solutions or suggestions on how to deal with this terrible dilemma of violence in Upper Sindh that is so deeply ingrained in people’s mindset, that it is taken as a fact of daily lived life rather than an aberration.

In one of the most graphic descriptions of what living in a violent environment entails, Shah recalls, how, during her tenure as Nazim, “I witnessed and lived in a world of fear, extreme trauma and pain evident during the funerals, the panic migrations and the absolute stillness in villages during the aftermath of destructions.” And experienced, on a daily basis nearly, “the intimacy of violence. Two images appear before me…the lament of women crying for relatives lost to violence and my empathising with them in their grief. The other is my daily social interactions with people, men and women, who have been either victims…or those who have been involved in the death of their near ones; my pretending not to know about these personal involvements shows the contradictory forms of such intimacy — one of empathy, the other of myself normalising such a world.”

All this, while being responsible, at one level, for maintaining law and order in the district.

Have things changed? The basic research for the dissertation was completed in 2004. But 12 years later, as the book was getting ready to be launched, Shah writes somewhat resignedly in the preface, “The newer stories I encounter echo, repeat, and reiterate what has been narrated here…The plots do not change, the characters do.” For anyone seeking a better understanding of this whole, very confusing issue, this is a book that demands to be read.