“There is more tolerance of transgenders, but still no real acceptance.” – Kami Choudhry

By Deneb Sumbul | Interview | Published 8 years ago

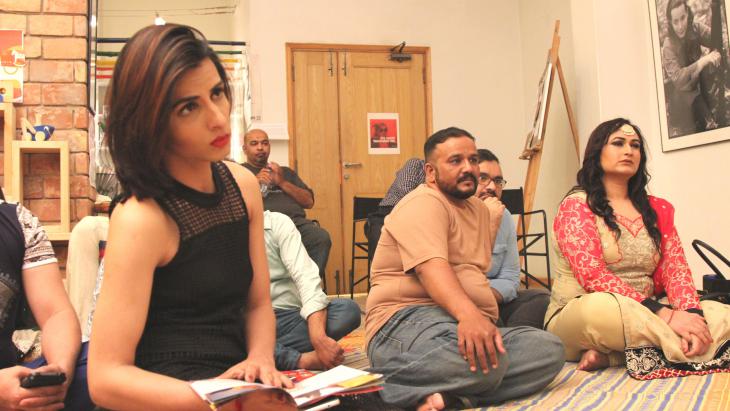

A svelte Kami Choudhry arrives on the dot for her interview with Newsline, dressed casually and completely comfortable in her own skin. An engaging conversationalist, in this marathon interview she shares her life story — hurdles, heartaches, accomplishments et al — punctuated with light-hearted banter and laughter. Only 27 years old, she has matured into a driven activist. Utilising every forum to highlight the grave issues that plague gender minorities, Kami is one of the brightest faces to represent her community.

After completing her studies in the Beacon House School system, Kami graduated with a B.Com degree from Karachi University. While still in her teens, she worked as an import assistant for a shipping line. However, her real career as a development professional began in 2012 when she joined Naz-Pakistan, a Karachi community-based LGBT organisation working for the health and human rights of gender minorities, as a community co-coordinator. Through her work with Naz Pakistan, Kami attended national and international conferences, travelling widely as a representative of her community.

She left Naz-Pakistan after five years, to start her own NGO by the name of Subrung, focusing on her areas of interest, that include human rights, gender, health, advocacy, leadership and education. Kami is also a focal member of the Asia-Pacific Transgender Network and is on the Boards of the Forum of Dignity Initiative, Rights Now Pakistan and Street to School. She is also an active member of the international organisation, Youth Lead, and a core group member of Youth Voices Count, Bangkok. For the latter organisation, Kami was the first transgender to represent Pakistan.

Kami has also been featured in documentaries, such as BBC Three’s How Gay is Pakistan? and an international award-winning 2013 documentary, Chupan Chupai (Hide and Seek), made by a Danish and a Pakistani filmmaker. However, her big breakthrough came last year, when Kami stepped into the fashion world as Pakistan’s first transgender model with a shoot that went viral, and won her both national and international acclaim.

As Pakistan’s first transgender model you broke boundaries in 2016. Do you think your photo shoot served as a breakthrough for others in your community?

I was uncertain at first, because I saw myself more as an activist. However, Waqar J. Khan, who had conceptualised the fashion shoot, was determined. What concerned me most was how certain public figures in Pakistan like Sabeen Mahmud and Qandeel Baloch had been targeted. But here was an opportunity for me to do something positive, so I thought why not? And because of it, I received recognition both nationally and internationally, which made me feel more confident.

I have already featured in two documentaries — BBC Three’s How Gay is Pakistan? by Mawaan Rizwan; and then I was one of four individuals featured in Chupan Chupai, a documentary that fetched two international awards, in which my character was quite flamboyant. Prior to my fashion shoot, I had shot for a short film, Rani. Initially, I thought I was unsuited for the poverty-stricken, weepy role. But the script was very interesting and not stereotypical. The production house sent 22 takes of mine to the US-based director of the film, and to my surprise, I was selected for the lead role. But generally speaking, society and the media have pigeon-holed us into stereotyped roles. After the modelling stint, I have not been invited to participate in any runway fashion show. However, recently I have done a four-page spread for the June 2017 issue of LIBAS International and a Sonya Battla fashion shoot for their August campaign.

In August 2015, I attended the Copenhagen Pride festival — Denmark’s annual festival that focuses on LGBT issues, and I was especially interviewed for a Copenhagen newspaper.

I believe that the media houses in Pakistan need awareness on gender issues and their content could do with a lot of improvement. The producers and anchors of morning shows on news channels are better than the ones on entertainment channels. They are more enlightened and know how to handle transgenders. After one uncomfortable experience at a morning show of an entertainment channel, I declined all other offers. They invite us to sing for TV dholkis or ask us to demonstrate our modelling for the catwalk. If shows want to include us in their entertainment segment, some degree of serious effort should be made to highlight the kind of issues we face in society. They only want masti-mazaaq from transgenders.

The same is true of films: In the recent Eid release, Mehrunisa V Lub U a very senior actor plays the part of a transgender and I’m quite sure they have portrayed the character in a negative light. In the upcoming, Rangreza, 100 transgenders will be seen dancing behind the male lead. In Ayesha Omer’s upcoming film Rehbra, three transgenders are shown in a negative manner in an item number. They wanted to include me in it, but I refused. How would I look prancing around showing my midriff in a film, when I am giving awareness-raising lessons to children about self-respect.

The media is dominated by male and female personalities. Producers and directors, especially women, are afraid that if transgenders are invited to a show, they might highjack it. So they portray us in stereotypical roles. Why can’t a transgender be a talk show host or an anchor?

How did your family react to the fashion shoot? Have they generally been supportive of you?

I belong to a conservative Punjabi family from Bahawalpur. After my modelling stint I’ve had a few issues at home, especially with one of my brothers. After the shoot he said, “Khandan ko badnam kar dia.” What did the khandan ever do for us? I retorted. I saw the difficulties my family faced, and the sacrifices my mother made, after the death of my father.

My father married twice and had eight children — four from the first wife and four from my mom, whom he married after he became a widower. I am the youngest of my two older brothers and a sister. My father passed away when I was in class 6 and my mother took on the responsibility of bringing up all eight siblings, including getting everyone married and settled. My mother is such an inspiration to me and to my family. She may not have been that educated, but she educated all of us and gave me the strength and motivation to continue.

Now they are all accepting of me, but I cannot discuss my gender and sexuality with them. I have faced a lot of sexual abuse attempts, but my family members never wanted to understand. My mother understands me the most. We are the two odd people in the family. We live in a patriarchal society and have to deal with misogyny. The tattoo on my hand says, ‘Mama’s little boy’ — a bitter reality for me, but for my mom, a positive statement.

Do you think it is now much easier for youngsters, who are uncertain about their sexual identity to get the relevant information on it?

Until 10 years ago, nobody wanted to discuss it. I was 22, when I identified myself as a transgender. Due to my feminine behaviour, my family would not let me out of the house, nor allow me to meet people. I thought I was abnormal till I was 18-19, until one day I felt I had had enough, and something drove me to find out what it was that made me different.

I studied at a Beacon House School, but even the teachers in such a big private school system do not have any gender sensitivity. Whenever I complained to the teachers that the boys were teasing me, they would say ‘join the girls.’ When I sat among the girls, they would make fun of me. This kind of environment has an impact on one’s studies, but it did not stop me from taking part in several extracurricular activities.

Youngsters who are confused about their sexual identity nowadays have access to information through the internet, or they know better whom to approach for guidance — like me, for example. So they have a better support system now.

I do the rounds of schools and colleges frequently, conducting awareness-raising sessions on transgenders, where I speak candidly on the subject with all age groups. Could you have imagined schools and colleges holding such talks even 10 years ago? I conducted sessions at two of Beacon House’s annual ‘The School of Tomorrow’ events, which are huge international educational and cultural festivals. Recently, I was on the panel of a TED-Talk at the FC College, Lahore. I was the last panelist, and I told them it was because they wanted to add tarka to their talk. Wherever I go I say, ‘Gender is in your head and sex is between your legs. So please do not put them in the same box. What you see is Kami and this is an expression of my gender.’ And you should see the reaction on people’s faces.

The new generation [of transgenders] has a platform; they are being provided with opportunities and told the difference between right and wrong. None of these avenues were available to us, there was no one to guide us. At least there is now room for discussion in private schools, but the real challenge lies in public schools.

Is society is becoming more tolerant of your gender?

Let’s say it is about 50-50. There is more tolerance, but still no acceptance. Had there been more acceptance, I would have been able to discuss my gender in my own home. I feel my family members are only tolerating me. I am the bitter pill that can’t be swallowed and can’t be spat out.

What is the biggest challenge that the transgender community faces now?

Mainly it is poverty and lack of opportunities. There may be only a handful of transgenders like me — perhaps 20 to 25 — who are vocal and are earning well. Most of them belong to the low-income group. When there is a lack of acceptance in society and stigmatisation at every level, you will automatically be relegated to the fringes.

Transgenders who have moneyed parents like us live a relatively khushal (satisfactory) life. Either they are supported monetarily, or the family sets them up so they can live their own lives, or they are sent abroad. Transgenders from middle-and low-income groups are the ones who have to face [the taunts] of society. I belong to a middle class family and even though they educated me, there was no form of support. Subsequently, one of my older brothers helped me get a job as an import assistant in a shipping company when I was only 19. Because of my hard work I was promoted to import executive, but I worked there only for two years.

How did you become an activist?

In 2012, I joined Naz-Pakistan, a community-led NGO working in the field of health and human rights of gender minorities. It was the first organisation that spoke on LGBT issues, along with HIV and Aids. As their community co-ordinator, I would counsel those who approached us, educate them on HIV and Aids, get free tests done for them and give demonstrations on the use of condoms. I worked with them for five years at a Drop-In Centre, and it was around this time that I identified myself as a transgender.

Subsequently, I left to form my own organisation called Subrung Society Pakistan, in which all of us work voluntarily. My organisation comprises several young people, including transgenders, gay men, and there is a trans-man (who has changed his sex from female to male) too. In a sense, Subrung represents people from all orientations. Our main focus is the sensitisation of society to transgenders. Currently, we are holding talks in schools and colleges. I have planned sessions at the Karachi University and Szabist. I love dealing with youngsters, especially when they ask mazay mazay kay sawal at the end of each session. I am not embarrassed by any question, no matter how awkward.

At a session in Beacon House school, one of the mothers — a doctor — asked me a question on surgery [relating to change of sex]. Her 12-year-kid was trying to stop her asking, but I encouraged her to go ahead. I explained all the biological differences, pre- and post-surgery, and she was appreciative.

We encourage transgenders to approach their local police stations whenever confronted with problems. And if help is not forthcoming from the police, we tell them to give us a call. We have built a network of contacts that come to our aid, such as Shehla Qureshi (the first woman in Karachi police to be given the rank of ASP), and other ranking police officials. Most police stations in Karachi know Bindiya Rana and me by name.

I was working very closely with the National Human Rights Commission and a parliamentarians group on the Sindh Transgender Protection Policy Bill 2017. Now I am part of a technical group organised by Naz Pakistan who have invited transgenders, along with civil society groups, to submit a petition in the Supreme Court (SC) to make amendments in the SC 2012 decision to give transgenders equal rights. It has been five years since we got some rights. Earlier, there were hardly any discussions on transgenders, but now our issues are taken up at so many forums. Recently, two bills, the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill 2017 and the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Criminal Law (Amendment) Bill, 2017 were tabled in the Senate.

Working among the “so-called” ‘straight’ (heterosexual) people sometimes meant getting pinched and teased by them, and I would reciprocate by making fun of them. Such circumstances are very hard to work under and you have to learn how to manoeuvre your way through them. However, gradually, there has also been more acceptability.

I have faced a lot of discrimination and there have been several [unsavoury] incidents in my life, but I do not dwell on them or allow them to affect me or else I would not have been sitting here. Now I respond to meanness by saying, ‘Carry on. How long can you continue to do this, darling? I will definitely cut your balls off.’ At the end of the day, it’s about how much you love yourself.

Many in our community suffer from anxiety and depression because of being marginalised. Transgenders were accepted members of society during the Mughal era. Attitudes towards them became intolerable during Zia-ul-Haq’s dictatorship. Since then, transgenders became more and more ghettoised and ended up in one profession.

I was born a male, with a female soul. I discovered I was different only when society made me realise it.

As an activist, you have made frequent trips abroad. How was the experience?

From my travels abroad, I learnt that education and how you present yourself are critical. I became a part of several international organisations. I even received two scholarships — one from Melbourne and the other from South Africa — both of which I couldn’t avail. I am a B.Com graduate and these days I’m studying for a Bachelors degree in Mass Communications from Allama Iqbal Open University.

I find that at many airports, the staff are not sensitised to transgenders. So the three hours of reporting time I get pre-flight, gives me ample opportunity to educate them. In the women’s cubicle, when the female staff scan me, I lecture them on transgenders. When I hand my passport at the counter, the staff do stare at me because I am usually made up to the hilt. I tell them that I am a transgender woman, known as khawaja sara in Urdu, and they are okay with it.

Have you thought of settling abroad?

The real fun is in working here. Where is the fun if no one whistles at you? Abroad they are so used to people like us that nobody even looks at you, no matter how flamboyantly you are dressed. Don’t you know how much we relish all the attention?

Which professions would be most suitable for educated transgenders?

Any. Working as teachers in schools would be a good starting point. Dawood Public School has asked me to provide CVs of educated and uneducated transgenders to accommodate them in their schools. Can you imagine the kind of awareness we could create from such platforms?

Ideally, there should be transgenders in the national and provincial assemblies. Those who have been part of formulating the Sindh Transgender Protection Policy Bill 2017, have brought this to the notice of political parties. PPP is a very liberal party and has promised to include me. InshaAllah, in the future you will see us in every field.

Do you see yourself as a role model?

When people approach me with their problems, or want to discuss transgender community issues, I see myself as a mentor who has reached this point after experiencing a lot of hurdles. For example, when runaway children suffering from a gender identity crisis arrive, I counsel them. They are mostly youngsters/boys of age 16 and above, who are trying to run away from their problems at home — mainly because they are effeminate. Several people have approached me through Facebook and other forums. I can counsel them, but I cannot help.

I explain to them that by running away from home they will only fall prey to predators, including gurus, who may extract unsavoury work from them. I encourage them to return to their families, to complete their education, and then do whatever they want, because without an education, they will never get ahead in life.

Have you worked with gurus and their chelas (minions)?

The gurus have a rigid mindset and can be as inflexible as others in society. Having been only in the business of prostitution, they feel they are doing fine and that they know whatever they need to know. Transgenders, who work as prostitutes, are a high-risk group for HIV and Aids.

I had no clue about HIV and Aids and condoms, but after working in the health sector for a year, I was so motivated that I started giving demonstrations on their use. In certain areas of Karachi like Landhi, we would find four to five individuals within one dera (household) infected with HIV and Aids. It was shocking to see that they lacked the basic knowledge of how the disease could spread while living as a group within the same space. Through communication we brought about a behavioural change in the community. Now transgenders insist on using protection, even when the clients don’t want to. It is not the transgenders who are spreading the disease — it’s their clients who have to be motivated by them to use protection.

We guide Aids-infected transgenders who cannot afford treatment to sources of free treatment and medication. They have to get themselves tested every six months for their viral load. We train them to look after themselves — and not to expect a third person to do it for them. They are taught not to resort to drama if they feel they are being unfairly treated, but to call us for assistance. A friend’s chela, who was working in a famous salon, tried to commit suicide after she contracted HIV and Aids. I’m glad that I motivated her to the extent that now she is leading a happy life. I feel it is the tension that comes with the illness that kills. I suffer from migraines every second or third day, and I have been a heart patient since 2013.

Do you feel that the transgender community is divided?

Yes, but it varies from area to area, and is based on preferences. The mentality of the khawaja sara communities in Karachi is dissimilar to those in interior Sindh. The ones in Punjab have a different outlook. Since I am a self-realised transgender, I am not part of the khawaja sara community and I am nobody’s chela — and there are several like me. Most of the time, I face discrimination when I am among the khawaja sara — to them, I am not a transgender.

Unfortunately, a few NGOs working on transgender issues have used the term `shemale’ as part of their organisations’ name. Shemale is a porn word. Even those working in the porn industry find it derogatory. (Note: Internationally many transgender people regard the term ‘shemale’ as offensive, arguing that it mocks or shows a lack of respect towards transgender individuals). Strangely enough these NGOs are run by well-known transgenders themselves. It is all about lack of awareness within the community and when you try to explain it to them, they are very offended.

Are you in any relationship?

I have been in an eight-year relationship and we have been together only because of him; otherwise we are two very different people. I am excitable, while he is a very calm and stable person. In a way we complement each other. He is a companion who has supported me at every stage of my life and I invariably turn to him for advice. Many times I felt he would leave me, but he never did. Also, I am very lucky to have some very sincere people as my friends and guides and a few family members.

What is your social life like?

I have a very hectic social life. I share my home with many friends, who are constantly in and out, and with those who are currently going through issues at home because of their gender.

The writer is working with the Newsline as Assistant Editor, she is a documentary filmmaker and activist.