Bone of Contention

By Newsline Admin | Newsbeat National | Published 8 years ago

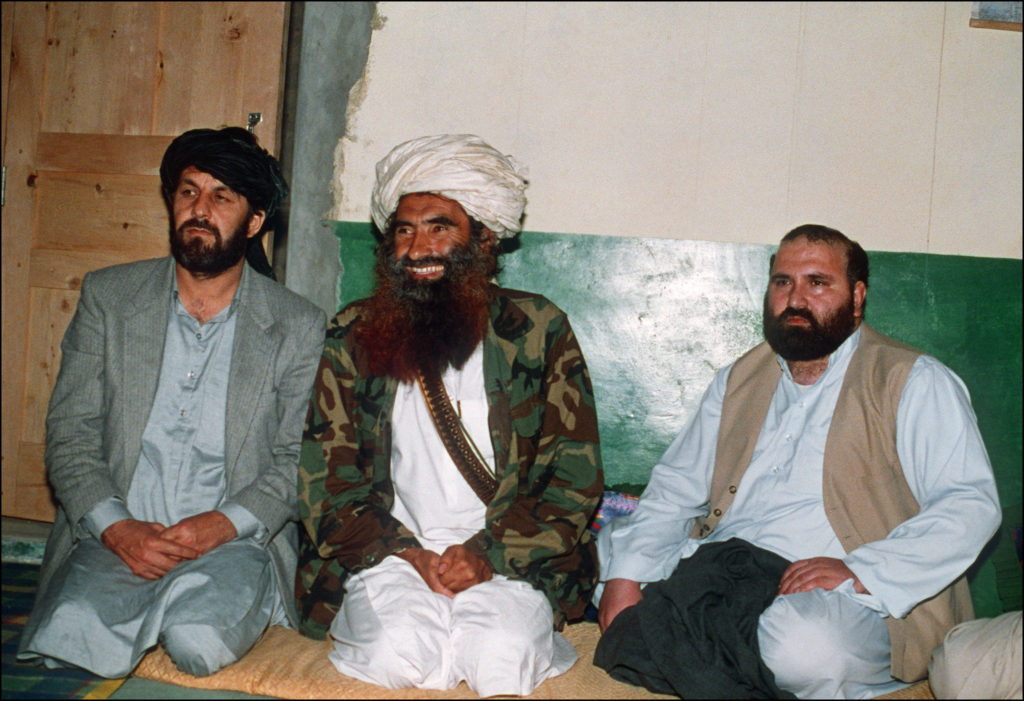

A picture dated 02 April 1991 shows Afghan commander Jalaluddin Haqqani (C) at his Pakistani base in Miram Shah with top guerilla commanders.

During the Afghan war against the Soviet occupying forces in the 1980s, the Haqqani network founder, Maulvi Jalaluddin Haqqani, was considered as one of the most effective mujahideen commanders.

Haqqani, who studied at the Darul Uloom Haqqania seminary in Akora Khattak in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s Nowshera district, successfully defended his base at Zhawara in Khost province, when the Soviet forces, with the backing of airpower, attacked it for days. Later, in 1991, he led the assault that resulted in the fall of Khost, the first Afghan city captured by the mujahideen after the February 1989 withdrawal of the Red Army. All these years, his family lived in Miranshah, the headquarters of North Waziristan, and later at a nearby village, Danday Darpakhel.

Such was his fame that the CIA was keen to support him during the war and the ISI was aware of his firepower. Influential US Congressman, Charlie Wilson, who lobbied and got millions of dollars assistance to the Afghan mujahideen, reportedly liked him so much that he described him as “goodness personified.”

Despite occasional reports in the media about Haqqani’s death, his family has maintained that he is alive. Even if he is alive, the 78-year old cleric-warrior must be in poor health. His last statement, urging Taliban fighters to continue to resist the US-led foreign forces in Afghanistan, was issued in November 2013, following the assassination of his eldest son, Naseeruddin Haqqani, in Bara Kahu near Islamabad by unknown gunmen. He termed his son a ‘martyr in the path of jihad’ and offered felicitations to the Taliban leadership and fighters on his martyrdom.

When he fell ill, the elder Haqqani passed on the mantle of leadership of the Haqqani network to his second son, Sirajuddin Haqqani, who is now in his late 30s. The US placed a $5 million bounty on his head in 2009. Subsequently, the US announced a hefty reward for informants who could help in the capture of his two brothers, Naseerudding Haqqani and Badruddin Haqqani, both of whom are now dead. Out of the eight Haqqani brothers, four have already been killed in US drone strikes, or in fighting with foreign forces in Afghanistan. Another younger one, Anas Haqqani, is in the custody of the Afghan government after his capture by the US authorities in Bahrain about two years ago, when he was returning from a meeting with Afghan Taliban members in Qatar. Anas Haqqani has been convicted by a court and sentenced to death, but Kabul hasn’t implemented the order so far. The Haqqani network has kidnapped several western teachers, aid workers and tourists in Afghanistan, in a bid to exchange them for the release of Anas Haqqani and some of its other prisoners. It has threatened to exact revenge on a big scale if Anas Haqqani is executed.

The US designated the Haqqani network as a foreign terrorist organisation on September 7, 2012 and imposed sanctions on several of its leaders. It has been alleging that the Haqqanis are being allowed to run their operations from Pakistan and is asking Islamabad to take action against them. Admiral Mike Mullen, the retired chairman of Joint Chiefs of Staff, had once claimed that the Haqqani network was the veritable arm of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). Both the Haqqani network and Pakistan have denied the allegation. Following the Zarb-e-Azb military operations launched in June 2014, Pakistan announced that all militant groups, including the Haqqani network, had been evicted from their strongholds in North Waziristan and most had escaped to neighbouring Afghanistan.

Ironically, the US hasn’t declared the Afghan Taliban group as terrorist, even though the Haqqani network is part of it and the two carry out joint operations. The Haqqani network’s operational commander, Sirajuddin Haqqani, is also the deputy leader of the mainstream Afghan Taliban movement. His nominees were part of the Taliban delegation that held one round of peace talks with the Afghan government in Murree, on July 7, 2015. Moreover, the Haqqani network was part of the prisoners’ swap, between the Taliban and the US, brokered by Qatar more than two years ago. Under the deal, the Haqqani network released the US soldier, Bowe Bergdahl, whom it had captures in exchange for five important Taliban members held for years at Guantanamo. The tag of being a terrorist organisation didn’t stop Kabul and Washington from talking to the Haqqani network and making deals with it.

The strength and capabilities of the Haqqani network are often exaggerated by the Afghan and US governments. If one were to believe Sirajuddin Haqqani, he told this writer during an interview some years ago that his network had about 2,000 fighters. Obviously, he wouldn’t have downplayed his role in the insurgency in Afghanistan and it is possible that he gave a higher figure of his network’s strength in the interview. If true, then his share of fighters is small, considering the fact that the Afghan Taliban claim to have more than 100,000 active fighters. The US estimate of the Taliban’s fighting strength was 25,000 earlier and the updated figure is a bit higher. Making an accurate estimate of the Haqqani network’s actual strength has become difficult in recent years as, unlike in the past, it no longer makes claims about attacks undertaken by its fighters.

Whatever its strength, the Haqqani network is routinely blamed for most of the attacks in Kabul and several other provinces, despite the fact that the Haqqanis belong to Khost province and have a proven presence only in the neighbouring Paktia and Paktika provinces and in Kabul. It was also accused of undertaking an attack inside the Governor’s House in Kandahar last year, in which the UAE ambassador to Afghanistan and six other diplomats and several senior Afghan officials were killed, even though there has been no evidence to-date that the Haqqani network is operating in southwestern Afghanistan, including Kandahar.

However, there were some major attacks that bore the hallmark of the Haqqani network. These include the attacks on the Serena Hotel in Kabul and on Indian diplomatic missions. It may also have helped Jordanian physician Dr Humam Khalil Abu Malal al-Balawi conduct a suicide attack on the CIA station in Khost in 2010, killing seven of its agents.

One of the reasons the Haqqani network is being blamed for most major assaults could be that the US is attempting to justify its decision of declaring it a terrorist organisation and, at the same time, trying to hide the shortcomings in its own security network. Besides, blaming the Haqqani network also means indirectly putting the blame on Pakistan, as the Afghan and US government have been alleging that Islamabad is harbouring its members. The old links between the Haqqanis and certain international militant groups such as Al-Qaeda is another reason why it is singled out for blame and termed as the most pervasive and virulent group that needs to be eliminated.

President Donald Trump’s angry outburst against Pakistan in his August 22 speech also had something to do with Washington’s strong belief that Islamabad had allowed the leadership of the Haqqani network and the Afghan Taliban to make use of Pakistani territory, to wage war against Nato and Afghan forces in Afghanistan. Pakistan categorically denies the existence of safe havens for the Afghan Taliban and the Haqqani network in its territory. It criticises the US for making it the scapegoat for its own failure in enforcing a military solution in Afghanistan over a period of 16 years. As a result, the stage is set for further deterioration in Islamabad-Washington relations. One of the major factors for increased hostility between the two erstwhile allies would be the Haqqani network. n