To Write is Wrong

By Aasim Zafar Khan | Newsbeat National | Published 9 years ago

“We’re all waiting for our turn to disappear,” says my friend S, a longtime stalwart of the human rights movement in Pakistan and an active member of civil society. “There’s no light at the end of this tunnel.” These words are a complete turnaround from a man who had always expressed hope about where this country was headed. “We have to keep pushing,” he used to say. Not anymore.

The case so far: four social media activists and one poet/academic were picked up from different areas of the country in early January. The most famous of them was the poet, Salman Haider, who is not only a fierce and vocal human rights activist, but is also a Shia Muslim, which already marks him out as a potential target for many Islamist groups. While no direct links with activism that could ruffle feathers in the establishment were ascertained for the others, it is alleged that between the four men, they ran three pages on Facebook which irked the establishment: Bhensa, which took a particularly savage yet satirical view of the state religion, Islam; Mochi, which questioned the role of the armed forces and its intelligence wings; and Roshni, which promoted secularism.

The case so far: four social media activists and one poet/academic were picked up from different areas of the country in early January. The most famous of them was the poet, Salman Haider, who is not only a fierce and vocal human rights activist, but is also a Shia Muslim, which already marks him out as a potential target for many Islamist groups. While no direct links with activism that could ruffle feathers in the establishment were ascertained for the others, it is alleged that between the four men, they ran three pages on Facebook which irked the establishment: Bhensa, which took a particularly savage yet satirical view of the state religion, Islam; Mochi, which questioned the role of the armed forces and its intelligence wings; and Roshni, which promoted secularism.

What lends credence to the allegation that these individuals were running those pages is the fact that in the immediate aftermath of their disappearance these pages either disappeared, or were taken over by ultra-nationalist groups operating on social media. A case in point is the Bhensa page, which now reads: “This page is now run by the Elite Force of Pakistan. All blasphemous and offensive material has been removed. Pakistan and Islam ZB.”

It is important to mention that two of the five activists were actually overseas Pakistanis, in that they were working and living abroad: in Singapore and Holland, and were only visiting the country when they were picked up. This has led people to extrapolate that the activists were already on the radar of whoever picked them up, and the moment they landed in the country, their abduction was set in motion.

Following pressure from civil society outside, and the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) in parliament, on January 10, Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan said that the “safe recovery of the missing social activists is a priority of the government.”Two weeks later, there was still no sign of them.

With the government seemingly incapable, or perhaps unwilling, to look into the case of the missing social activists, the onus fell on civil society to ensure that the matter remained current and did not disappear in the deluge of daily scandals that continue to dominate the news cycle.

The problem, however, is that Pakistan’s civil society is weak and fragmented. “We don’t trust each other and in the past have hurled serious allegations against each other,” says lawyer and political activist Jibran Nasir. “Today I’m being called a RAW agent. Two years ago, I was branded an ISI agent.”

This fragmentation meant that although there were protests against the disappearances in multiple cities across the country, the campaign was starting to lose strength.

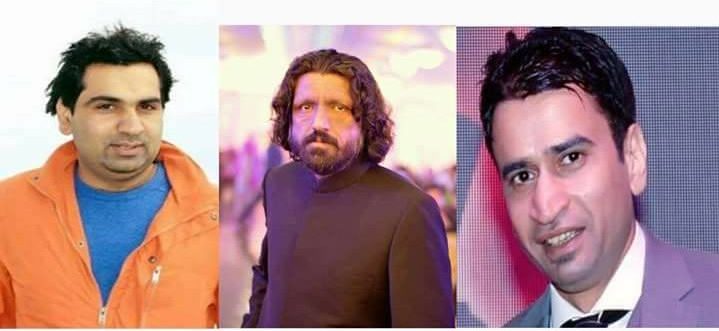

But miraculously, on the night of Friday, January 27, Salman Haider and Ahmed Raza Naseer made contact with their families to say they were alive. Two days later, on the 29th, Asim Saeed and Waqas Goraya also returned home. At the time of writing, Samar Abbas, President of the Civil Progressive Alliance Pakistan (CPAP), has still not been recovered.

Experts believe the international attention that the abductions got, played a vital role in ensuring that they were recovered. Publications and electronic media including, but not limited to, The New York Times, the BBC, the CNN, the Guardian, Al Jazeera and the South China Morning Post, all carried the story. “Had the bloggers not had this kind of attention, they’d still be missing,” S says.

One activist still remains missing.

“The only thing civilians can do is keep reminding the government. And the press can continue to cover press conferences,” says Nasir. “I will ensure that this issue is not forgotten,” he says.

The government’s silence on the matter has been telling. “They’ve actually shown their culpability in the curtailment of freedom of expression,” says Raza Rumi, consulting editor for The Friday Times and author of The Fractious Path: Pakistan’s Democratic Transition. “Let us not forget that the cyber crime law was passed with the full involvement of the federal government and parliament, and therefore it also suits the interests of the sitting government that they can have some form of control over online dissent.”

The cyber crime law that Rumi refers to, has been at the centre of much debate in the country’s civil society because of its restrictions on human rights and speech.

And the issue is not just the disappearance of the activists. Immediately after the event, numerous ultra-nationalist groups started a malicious campaign on social media, calling some of the activists “blasphemous,” and the others “anti Pakistan.”

“This is a totally orchestrated campaign,” says Nasir. “And whoever is behind it does not realise the end game; they are burning their own home.”What Jibran Nasir is referring to are the series of accusations that have been hurled against the disappeared, not only on social media, but on mainstream television as well: accusations of blasphemy and treason, which are not only punishable by death under law, but have also been used as triggers to incite violence, or even murder.

As of now, the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA) has indefinitely banned Amir Liaquat and his show on Bol Television with immediate effect for preaching hate, stating that the host “has willfully and repeatedly made statements and allegations which are tantamount to hate speech, derogatory remarks, incitement to violence against citizens, and casting accusations of being anti-state and anti-Islam, against various individuals. At the same time, a First Information Report (FIR) has also been lodged against the said individual under the Anti-Terror Act for intimidating the public and spreading public hatred.”

While these are steps in the right direction, numerous pages and groups exist online and continue to operate which accuse the missing activists of either blasphemy, treason or both. Another case in point is a page known as Cartoons by Nazgul Baloch, which has routinely asked its nearly 60,000 followers to support the charges brought by Amir Liaquat against the activists. The true test of the government then, will be how it responds to these online spaces being used to spread malicious allegations and inciting violence, or worse, against individuals that do not adhere to what is ‘the accepted point of view.’

Most people expect that with the recovery of four of the missing activists, Samar Abbas, the last remaining one, will also reappear. However, the abductions have sent a clear message. “The ability to dissent and differ from the state narrative is limited and it is no longer safe to do so,” says Rumi.

The writer is a journalist based in Lahore. He is the current managing editor of MIT Technology Review Pakistan, a bi-monthly science and technology magazine.