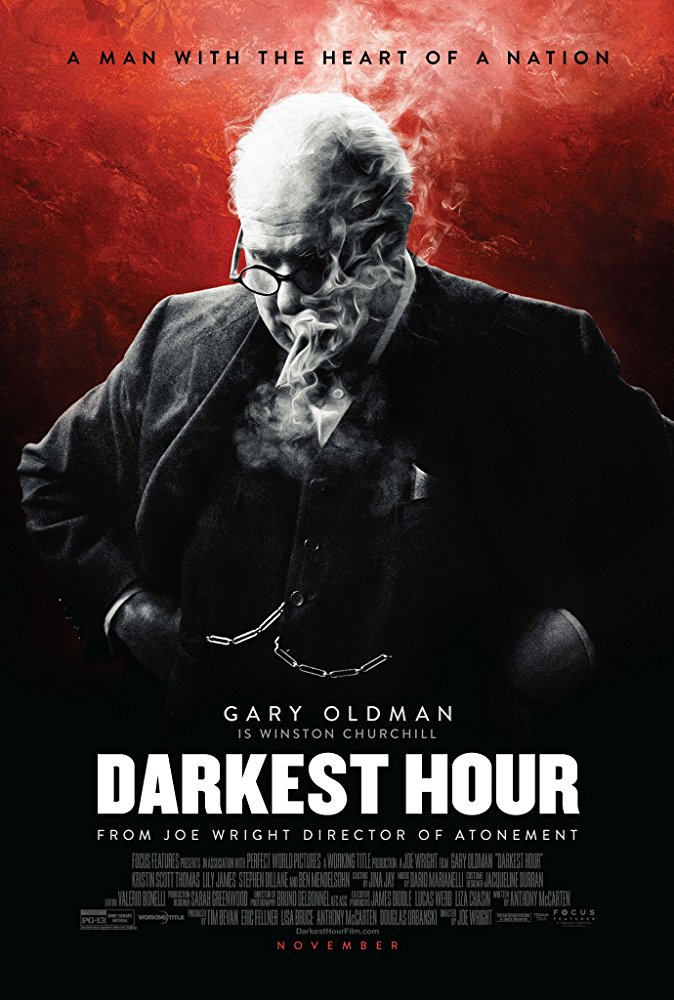

Movie Review: Darkest Hour

By Ali Bhutto | Published 7 years ago

On the surface, Joe Wright’s film, Darkest Hour, is like a morale-boosting speech by Winston Churchill: it serves as the opium of the people — moviegoers in this case. Its historical accuracy and integrity, however, are questionable. And like Churchill, the film relies largely on stirring in the viewers a sense of bravado and hedonistic patriotism. If there is any depth to be found beneath this veneer, it is in the portrayal of the social awkwardness and lonesomeness of Churchill as a man, and his ‘outsider’ status among his own party men.

On the surface, Joe Wright’s film, Darkest Hour, is like a morale-boosting speech by Winston Churchill: it serves as the opium of the people — moviegoers in this case. Its historical accuracy and integrity, however, are questionable. And like Churchill, the film relies largely on stirring in the viewers a sense of bravado and hedonistic patriotism. If there is any depth to be found beneath this veneer, it is in the portrayal of the social awkwardness and lonesomeness of Churchill as a man, and his ‘outsider’ status among his own party men.

While Gary Oldman bagged an Oscar and Golden Globe for Best Actor for his brilliant performance as the controversial wartime prime minister, this does not redeem the less glorious aspects of the film, such as its biased nature and the narrow lens through which it approaches history. Darkest Hour is the latest in a series of motivational propagandist movies. If, in Rocky IV for instance, the all-American hero bravely fought the big bad Soviet empire despite the odds, then perhaps Darkest Hour attempts to nurse audiences through Brexit, by keeping spirits high the way Churchill did in the face of a seemingly infallible German juggernaut.

The plot revolves around the first few weeks of Churchill’s appointment as prime minister and his efforts to convince fellow party members to choose war against Hitler over appeasement. “You can’t reason with a tiger when your head is in its mouth!” he argues in a meeting with cabinet members, who are hell-bent on peace talks with Hitler.

While Churchill’s final speech in the House of Commons teeters towards the overly melodramatic, the high points of the film lie in its understated moments. These include the leader’s initial helplessness in the face of conspirators within his ranks, namely the ousted PM and Conservative party leader, Neville Chamberlain (Ronald Pickup), and the PM-in-waiting, Lord Halifax (Stephen Dillane). Their game is to push Churchill to state on record that he is against peace talks, after which the two will resign from Parliament, triggering a vote of no-confidence against the PM.

One could almost argue that the real motivational element in the film is not the fight against fascism but the way in which naysayers in the PM’s own backyard are dealt with (shades of Brexit!). This subtext humanises the figure of Churchill, who stands by his convictions despite being made to look foolish. And it isn’t all about the invincible one-liners for which the man is famous, either. In an attempt to appease a relentless Halifax, the PM simply admits, “Look, I need you.” In other instances, he just mumbles.

A memorable moment is when Churchill delivers his first address to the nation via radio, unflinchingly declaring that Britain was in complete control in the fight against the Nazis, when in fact it wasn’t. He emphasises to a disapproving Sir Anthony Eden, the need to “inspire” his countrymen: “I am going to imbue them… with a spirit of feeling they don’t know yet they have.”

Yet there is a major sequence in the film that is purely wishful thinking on the part of the director, portraying a Churchill he would rather have existed. The PM takes King George VI’s (Ben Mendelsohn) advice — “Go to the people” — and uses the London Underground for the first time in his life, where he meets a coterie of commuters who represent a cross-section of British society. Consultations with them only reinforce his own beliefs and, conveniently, by the time he reaches the tube stop for Westminster, he has the answer to his problems.

Notwithstanding the fact that artistic recreation can be effectively deployed to capture the essence of a historical figure, this scene stands on weak ground on all counts. It is the film at its proverbial ‘darkest hour.’ The cheap, Bollywood-like vibe of the entire subway sequence is at odds with the rest of the production — almost as if a different director was behind it. Wright would have fared better had he acknowledged Churchill’s bigoted nature and incorporated it in the character, allowing viewers to see several sides of a complex individual. But then the film lacks the depth to be able to pull this off.

The writer is a staffer at Newsline Magazine. His website is at: www.alibhutto.com