Flight or Fantasy

By Nusrat Khawaja | Art Line | Published 7 years ago

A child experiences a sense of wonderment upon opening the pages of a pop-up book. The flatness of the page is transformed into a three-dimensional structure in which perforated shape and space, colour and image interact convincingly to create illusory worlds within which the imagination delights.

Masooma Syed has rekindled the enchantment of miniature worlds with her show at Canvas Gallery. Titled Spirits (and this is not random), the show comprises eight distinctive dioramas, displayed within acrylic boxes set upon white, wooden podiums.

The dioramas are scaled down models from seemingly real-life scenarios, whose re-creation the artist has likened to: “Spotting locations, lights, sites and like a theatrical play, drama and hallucination of a thousand stories within stories.”

She has played on the meaning of “spirits” by incorporating material from discarded alcohol cartons as building material for walls and partitions. Within the boxes, she has worked with collage by using cut-out shapes of buildings and people and placing them at carefully interpreted distances to deliver an impression of accurate proportionality as in trompe l’oeil. Her materials include painted embellishments, LED lights and found objects.

In the spirit of a philosopher-journalist, Masooma explores spaces that raise and lower human spirits often within the same diorama.

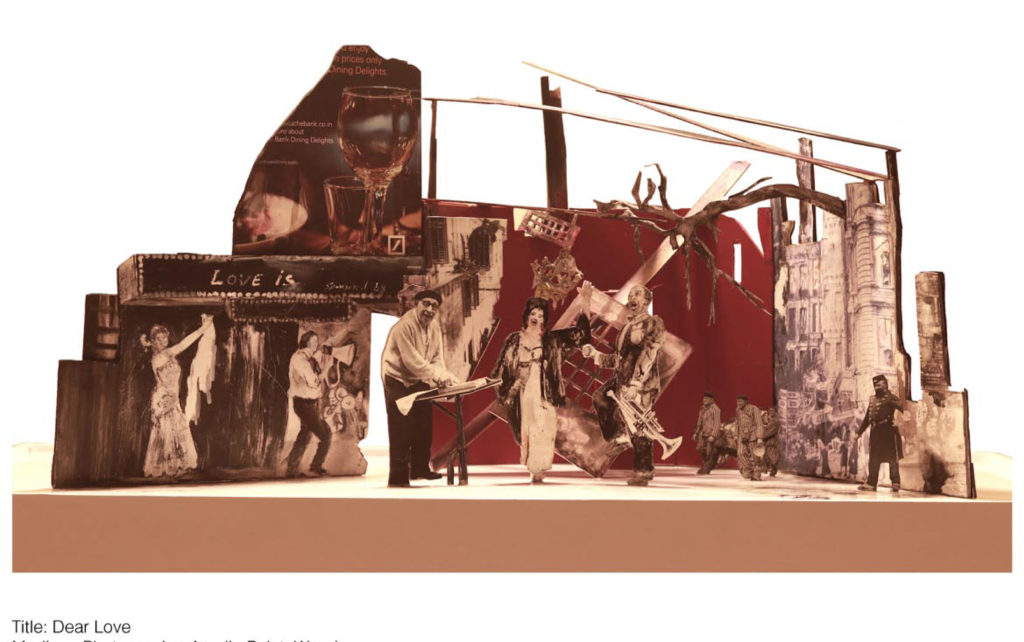

Her work titled ‘Dear Love,’ uses imagery from photographs and painted figures to create a nightclub scene where musicians and singers perform with gusto. Yet in the background, are two figures in striped clothing who may be prisoners in a labour camp. The mixed narrative is subtle but definite and underscores the scene with irony. The spirit of fun and the spirit of repression represent two different dimensions of human sociology.

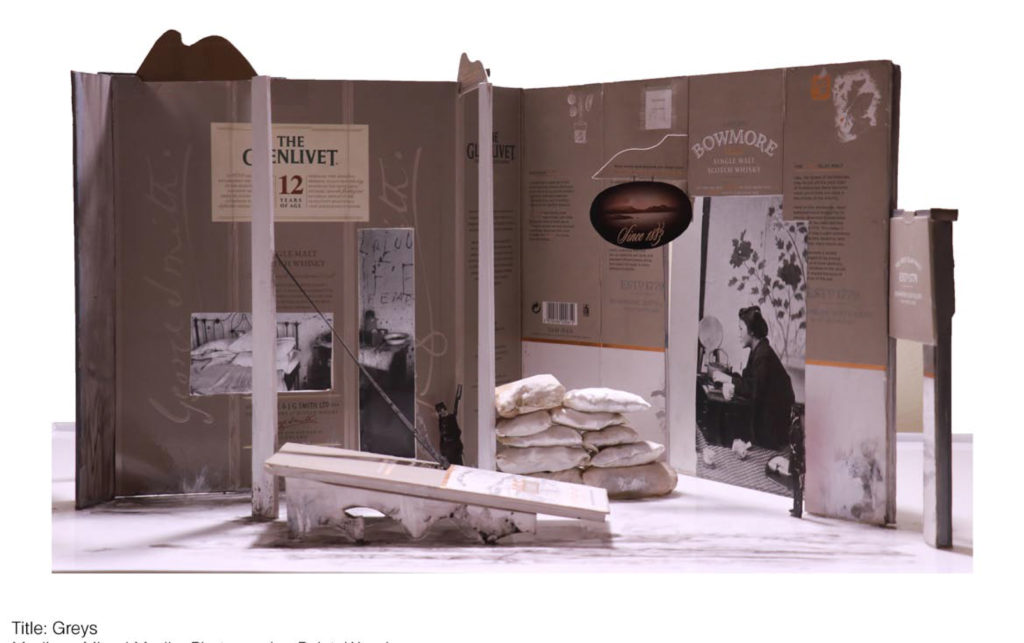

A similar sense of disquiet is evident in ‘Greys.’ The sandbags in the foreground imply conflict. In the background, a young woman in Japanese attire can be glimpsed as she applies make-up.

Architecture features strongly in Masooma Syed’s work. Whether as imposing columns as in ‘Tables are for Moon’, or interior walls as in ‘Centenuary’, architecture is used to establish ambience.

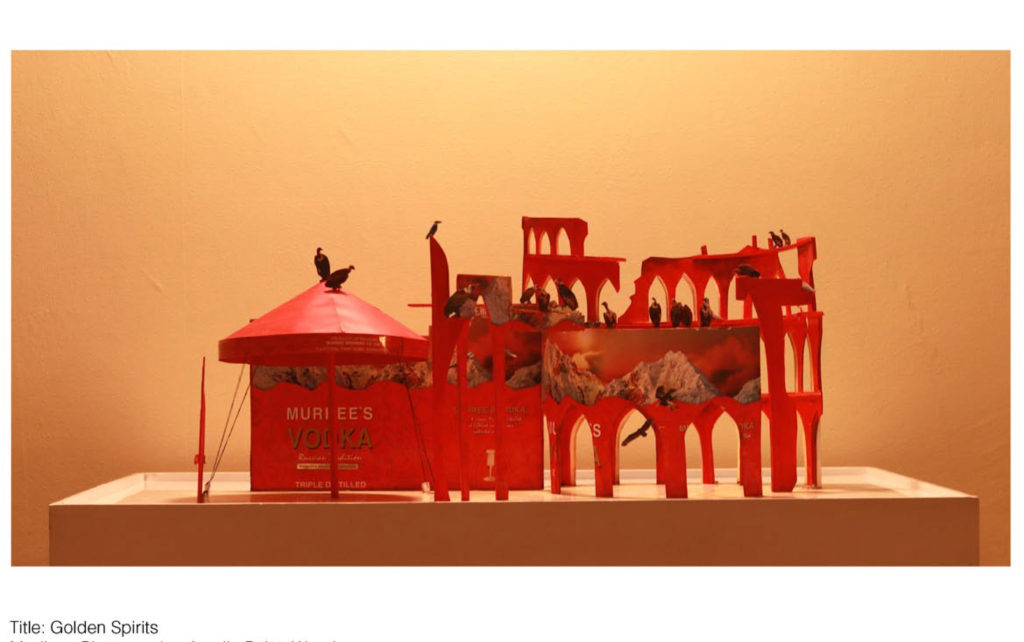

No human figures are present in ‘Golden Spirits’ and ‘Hall of Mirrors.’ Yet there is a palpable sense of human history having unfolded within these structures. The perforations of triangular arches in the deep red walls of ‘Golden Spirits,’ almost conjure the feel of wind and history flowing through the spaces. The walls are broken in places implying that the structure is very old. Vultures sit atop the ramparts — like spirit animals of architectural ruins — claiming the seemingly abandoned place for themselves.

‘Hall of Mirrors’ recreates the columned portico of a Mughal-style loggia. The accuracy in scale of the original buildings, that have inspired the miniaturised reproduction, has been maintained.

Masooma Syed speaks of the instinctive process that shapes her art. She has worked with extremely varied structural materials in the course of her career such as human hair, bones, feathers and fingernail parings. In the ‘Spirits’ series, her experience of the world, informed by the places she has lived in, comes through in the theatre-like constructions. The carefully chosen elements for the mise-en-scene contribute to the evocation of mood associated with particular places. The technique requires leaving out material as much as placing it within. The relationship between empty space and the deftly-shaped cut-outs is essential to the success of the process. The balance is a fine one and much more difficult to accomplish than it seems.

Masooma spends a lot of time in Sri Lanka, and the work called ‘Dutch Quarter’ is a good example of the integrative processes that underlies her approach to art. The word ‘spirit’ is given another layer of meaning as in spiritual. The diorama depicts a charming shrine with a sleeping Buddha/Jesus figure. Two men and two sari-clad women are seen from behind as they pray to the deity who lies in a wooden cot. Small black-and-white goats amble between the worshippers. The colours in this tableau — bubble gum pinks and royal blue — are vibrant and nuanced. They are reminiscent of the colour palette often used by Matisse (who incidentally, also revelled in paper cut-outs in his declining years) in works such as ‘The Pink Studio’ (1911).

These enclosed worlds, with their intimate proportions, are self-contained scenes in which time and place coalesce. We are Gulliver-like colossi looking in voyeuristically. We cannot enter, except by means of our imagination, which revels in the continuity between childlike wonderment and the massively complicated world of adulthood, in which experience mediates the untethered flights of fantasy.