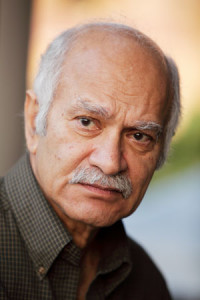

Interview: Zulfikar Ghose

By Ilona Yusuf | People | Q & A | Published 14 years ago

“All serious writers have dismissed the notion of what’s demanded by the market”

– Zulfikar Ghose

Born in Sialkot before Partition, Zulfikar Ghose’s early life was marked by frequent transitions: the family moved to Bombay, India, then to England, where he attended secondary school and college. Ghose graduated from Keele, then a new “redbrick” university where he became known as a poet and editor of a national anthology of student poems, Universities’ Poetry. From 1959, he juggled a teaching career in London along with freelance journalism and was part of a group of young poets and writers, many of whom including Ghose himself, hitherto became acclaimed poets, novelists and playwrights.

In 1969, Ghose moved to Texas and worked at the University of Texas in Austin, where he has written the majority of his novels. Over the last two years he has travelled to Pakistan, lecturing and conducting poetry readings at the Karachi Literature Festival and at local schools and colleges.

Although Ghose is often grouped among postcolonial writers, he distances himself from labels and stereotypes. Location and socio-economic and political conditions are not central to his narrative. What matters is expression, how a writer makes language new. Ghose’s contention, which forms the subject matter of several of the essays in In the Ring of Pure Light, is that when a writer focuses on form and language, the content, based on personal experience, will automatically unfold. This is in direct contrast to the trend, beginning in the ’80s, emphasising subject matter over form.

Since 2009, Oxford University Press has published three slim volumes of Zulfikar Ghose’s work, 50 Poems: 30 Selected 20 New, and two collections of essays, Beckett’s Company and In the Ring of Pure Light.

In this interview conducted via email, Zulfikar Ghose speaks about his life as an author and a teacher, and the art and craft of writing in an ostensibly market-driven literary world.

Q: What brought you to literature and the fine sensibility that inhabits your writing?

A: I have no idea what brings anyone to literature. I suppose one must be born with a brain with a predisposition that makes the person drift towards a certain direction and make it a preferred choice of action. As a teenager at school, first in Bombay and then in London, I was absolutely hopeless in science and mathematics but was the top student of the class in English.

The London of 1952-54, when I was at school there, had very few immigrants, and I was the only brown boy in an ocean of pink bodies, so perhaps there was a psychological motivation to show them I could excel in their language. I carried off all the prizes, including that for the best literary contribution to the school magazine. Consequently, the teachers were very supportive and encouraging; one lent me books from his personal library that he gave to no other student; another teacher took me to a café on a Saturday to discuss poetry, and on my last day at school the headmaster called me to his office, shook my hand, and said, “Keep writing,” which is exactly what I’ve done for the past 57 years.

Q: You ended up as a teacher in the University of Texas in Austin. What do you have to say about the experience of teaching at the university level?

A: In 1969, I was invited to teach in the English department at the University of Texas in Austin. In the earlier years I taught 20th century English and American poetry, modern European drama and gave a general course in literature. Then, for some 20 years, it was mainly creative writing. I worked at the university for 38 years.

It was indeed a very rewarding experience. The best part of university teaching is that one is continuously engaged with young minds who are intellectually eager to discover their own vast potential. And, one learns a lot from them, especially when they respond to the challenge of creativity and come up with strikingly avant-garde forms. Secondly, however well read a professor might be, he still needs to re-read the texts in order to be prepared for class, and I found this to be an excellent learning experience. Writers like Thomas Hardy, Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck whom I’d read as a schoolboy and an undergraduate, and believed then to be great, did not survive the re-reading which exposed their shortcomings and faults. I understood then that since most people don’t have the opportunity to re-read life in life, they hold on to the opinions formed in their earlier years when they were most impressionable and that probably accounts for the enduring high reputation of those writers.

Q: You are quietly insistent about the quality of some writers over others. For instance you consider Dostoyesvsky and Hemingway inferior in comparison to Chekhov and Faulkner respectively. How then, are we supposed to treat these writers when reading or teaching literature?

A: There is no formula, nor should there ever be one, to tell us how we are supposed to treat any writer. We are all creatures imbued with a unique set of prejudices and born with brains each receptive to a unique set of values. But while the consequent variety of opinions is perfectly normal, and even a good thing, I do believe that we should never accept received opinion as the expression of irrefutable authority.

Hemingway is an example I use because I happen to live in America where students are conditioned to believe that he is a great writer. When they took my class, I would simply ask specific questions with reference to some sentences or passages in certain Hemingway texts and the students would then begin to have doubts, and there would always be several who would then say that they’d never been impressed by him but had kept their doubts to themselves. There would be a few who would remain unconvinced and would hold on to the idea of Hemingway’s greatness. And that’s fine with me because the important thing is that even these students will bring to their reading a sharper questioning point of view.

I have often criticised professors for teaching literature as if it were a branch of the social sciences, spending the classroom time discussing some jargon-filled theory or reading literature from some narrow point of view — Marxism, feminism, structuralism, etc. — or making it into a talking point by giving courses with narrowly defined content, such as “The Fiction of Protest,” or “Irish Women Writers,” etc., where books are read because they fit into the theme of the course and not because they are any good. No one questions the quality of the work but everyone, and especially the professor, sits talking endlessly about the ideas in the books without realising that their solemn discourse is little more than trivial gossip and has nothing to do with literature. It is this kind of teaching, which is the majority approach from grade school to graduate school, with its narrow focus on content and its incapacity to evaluate that special quality of language, form and style which makes great literature, that results in a whole culture maintaining the delusion that some very third-rate writers are of the first rank.

I have often criticised professors for teaching literature as if it were a branch of the social sciences, spending the classroom time discussing some jargon-filled theory or reading literature from some narrow point of view — Marxism, feminism, structuralism, etc. — or making it into a talking point by giving courses with narrowly defined content, such as “The Fiction of Protest,” or “Irish Women Writers,” etc., where books are read because they fit into the theme of the course and not because they are any good. No one questions the quality of the work but everyone, and especially the professor, sits talking endlessly about the ideas in the books without realising that their solemn discourse is little more than trivial gossip and has nothing to do with literature. It is this kind of teaching, which is the majority approach from grade school to graduate school, with its narrow focus on content and its incapacity to evaluate that special quality of language, form and style which makes great literature, that results in a whole culture maintaining the delusion that some very third-rate writers are of the first rank.

Q: Who among the contemporary authors or poets, here and abroad, would you consider as fine writers?

A: There are many, though unfortunately some of the finest are not being published by mainstream publishers. However, I prefer not to mention names for the reason that some are good friends of mine and some whom I’d rather never know. With one’s living contemporaries, there are complex questions associated with literary politics, admiration, envy, delight, contempt — indeed, a whole gamut of emotions and prejudices — and it’s best to say what a writer friend in Brazil used to say when asked what he was reading: “Ah, I’ve gone back to the Classics, the ancient Greeks are still our contemporaries!”

Q: You began your writing career as a poet, and later switched to prose. Incidentally, your prose is equally poetic. Did this shift occur naturally, and is it possible to be an equally accomplished poet and writer of prose?

A: My first book was a volume of poems, and it’s true I was writing mainly poems then. But I was also doing some prose. My closest friend in those early years was B.S. Johnson, who has since been acclaimed as one of the major English novelists of 20th century. Also at that time, the American novelist Thomas Berger visited London and we became close friends and have been ever since. I suppose that, given the friendship of these two highly original novelists, it was inevitable that I’d try my hand at writing fiction.

My prose is often referred to as possessing a poetic quality. Perhaps that’s what it is. All I try to do is to present whatever the subject is in as precise a prose as I can create. Some early English reviewers, who knew I was born in Pakistan, called my prose “exotic”; others, knowing I also write poems, call it poetic. It really is neither; only, it is usually charged with vivid images. Read the opening pages of Dickens’s Bleak House, or any page of Proust. It is imagistic presentation, neither exotic nor poetic, but so hard-edged, so sharp and exhaustive on detail that were the object to disappear its description in their prose will still keep it alive.

As for writers who were accomplished, both as poets and novelists, many consider Thomas Hardy to be an eminent example. Joyce and Beckett both wrote poems, and Borges, who wrote fiction, poetry and criticism, was great at everything. Then there was the incomparable Raymond Roussell in France. Remember, too, that for some writers, the distinction between prose and poetry ceased to exist by the mid-20th century: what we compose are texts.

Q: Over the last two years, you have travelled to Pakistan, given talks and lectures as well as participated in the Karachi Literature Festival. How was your encounter with the emerging young writers in Pakistan? What would you consider the main differences in the writing environment and the opportunities available in each country?

A: For an old writer like me, it is a thrill to meet writers less than half my age who are just starting out and who have the same sort of enthusiasm that I had when I was their age. There are at least four of them (those writing in English) in Pakistan whose work I follow with a keen admiration.

As for the writing environment in the US and Pakistan, obviously freedom of expression is a sacred right in the US, while certain expressions in Pakistan can get one hanged — which has always struck me as a law designed by cowards fearful that their belief might not survive the test of intellectual enquiry. And obviously, too, American affluence gives more opportunity to students with grants and fellowships. As a result, there are thousands of graduates every year who are quite well educated. However, that does not mean that they are therefore going to be good writers. The great thing about any art is that it is produced by an individual and not by the educated majority. Some of the very greatest — Virginia Woolf, for one — did not have the opportunity to go to college, and some who did — W.H. Auden, for example — came away with a third-class degree. So, the future writers of Pakistan will not be handicapped by not having the advantages enjoyed by the Americans, for there will always be among them individuals who will produce art out of their own inner madness.

Q: What advice would you offer young writers, especially those who struggle to find time to practise their craft despite the demands of making a living. And then there is also the issue of bowing to the demands of the market in order to be published.

A: A writer’s life is a solitary one of necessity, but one’s motivation is greatly encouraged when one meets others with whom to share ideas. In cosmopolitan centres, people naturally find others who reflect their enthusiasms — and that is how groups and coteries are formed (some of which, incidentally, become the source of literary politics which can turn quite vicious!). But again, we are talking here in general terms as if there is a body of rules, or some pattern, to which writers belong, when the truth is that often the great writer’s background has been that of one who had spent years in solitary confinement.

As for struggling to find time despite the demands of ‘making a living,’ I am not at all sympathetic with people who make that excuse for not producing work, for many artists have had to overcome that struggle. James Joyce lived a life of hardship and poverty in a godforsaken outpost called Trieste and then in Rome, having to work long hours at some menial job with a wife and two children to feed, and he still found the time and energy to write Ulysses. And Sylvia Plath, after she had been abandoned by her husband, living in a cold flat in London with two babies who demanded all her attention, would get up at four in the morning to find the time to write the terrific poems in her book Ariel. And if I may add a personal note: during the first two years after we were married, my wife and I lived in a two-room flat in London. I worked as a schoolteacher, which meant I left home at eight in the morning and did not return till five in the afternoon — and being a school-teacher is no picnic — and then made the time, which meant working till 1am in the morning, to write The Murder of Aziz Khan.

As for “bowing to the demands of the market,” this depends on the individual. There are writers who are prepared to make any compromise in order to be published and those who write only according to what William Faulkner called “the dictates of the heart.” Flannery O’ Connor despised writers whose only interest was “in seeing their names at the top of something printed, it matters not what. And they seem to feel that this can be accomplished by learning certain things about working habits and about markets and about what subjects are currently acceptable.” All serious writers have dismissed the notion of what’s demanded by the market. Flaubert said, “A writer can go far if he combines a certain talent for dramatisation and a facility for speaking everybody’s language, with the art of exploiting the passions of the day, the concerns of the moment.” I myself do not see any point in writing that which will serve the market, to do which is merely to provide a consumer product calculated to sell. I work following some obscure inner compulsion that is usually a curiosity about some new form within which I create a style that gives to the final language of the piece some revelatory glow that illuminates reality. Sometimes the resulting book interests a publisher, sometimes it does not. I have four novels that no publisher has wanted; they are as good, or bad, as anything of mine that’s been published, it’s just that they’re different. That rejection, however, has not persuaded me to abandon my inner compulsion and meet the demands of the market instead. As Flaubert said, publication and success are incidental, secondary effects.

Q: But every writer needs to be read. Who is your audience, particularly keeping in mind your exacting approach to literature? Also, does this issue matter to a committed writer?

A: “Art for art’s sake” has become a pejorative phrase in some minds who think that literature must serve as a sort of purgative to get rid of some imaginary intellectual impurity. In any case, slogans are usually suspect and are coined to arouse the ignorant mob against something or someone superior.

A writer does not have a need to be read. That is a question of a person’s vanity, not of his interest in wanting to create something new, which is the artist’s obsession.