Gateway to Global Recovery

By Shahid Javed Burki | Published 8 years ago

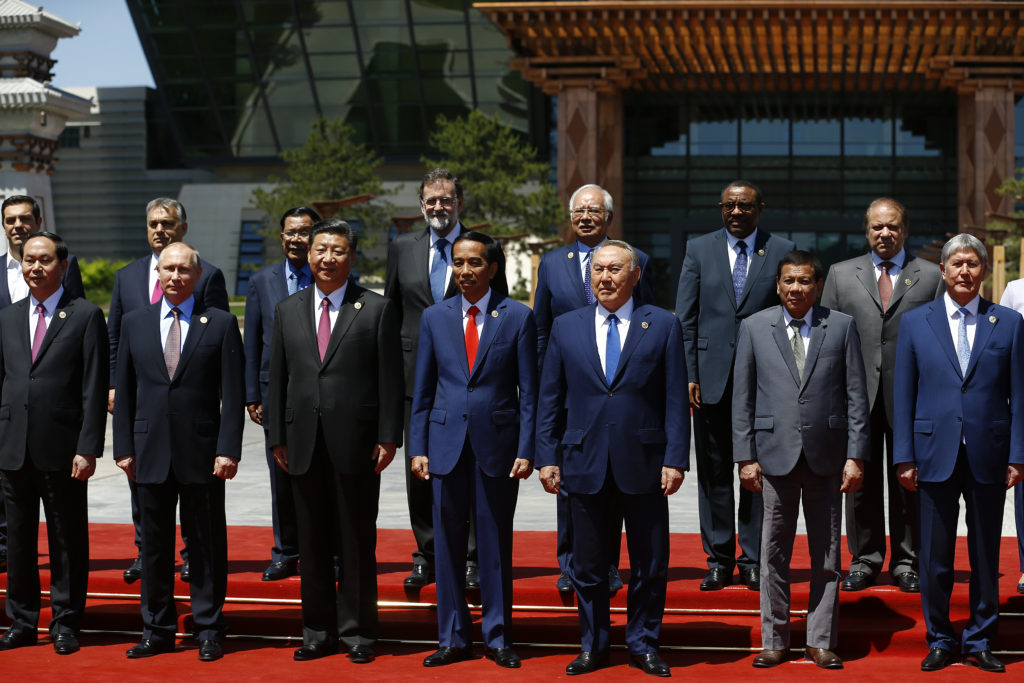

World leaders at the International Conference Center in Yanqi Lake

By the early 1990s, the leadership in Beijing believed that it needed to change its development paradigm. The process of economic growth had to become more inclusive; areas that had not benefited from the breakneck speed of economic change had to be brought in. China needed to extend growth to the areas outside the narrow strip of land on the east coast. Some 500 million people, more than a third of the country’s population, were packed into the area that stretched from the northern port city of Dalian to Shenzhen in the south.

In pushing forward this beyond-the-seacoast development plan, Beijing allowed considerable latitude to the local people in the interior provinces. A good example of the approach adopted by the left-behind provinces is Guizhou, not far from the border of Myanmar. There the Governor, Chen Min’er, a favourite of President Xi Jinping, used mostly borrowed funds to invest massive amounts of resources in infrastructure and housing. Being near the southeastern border, Guizhou will become a gateway for China’s access to East Asia. I can see similar developments taking place in China’s west, from which links will be made to countries such as Pakistan, Afghanistan and Kazakhstan.

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is one component of a larger programme labelled the One Belt, One Road initiative. It is also referred to as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), as was the case in Beijing in May 2017, when China hosted a summit of more than 50 countries. BRI is expected to involve Beijing’s investments in 68 countries and will cost more than a trillion dollars. On the eve of the Beijing Summit, Xiao Yaqing, chairman of the Beijing-owned Assets Supervision and Administration, provided some data on the programme. According to him, 47 Chinese central government-owned state enterprises were involved in implementing the programme in 1,676 BRI projects. A Financial Times report, however, stated that a number of state-owned enterprises were being pressured into working on the BRI projects. As such, they may not have done a careful project analysis to make sure that the activities being financed made economic and social sense.

The CPEC has two components: corridors and power generation. A new trade route will run from Kashgar in China’s Xinjiang Autonomous Region to Gwadar, a deep seaport in Balochistan, Pakistan. The first phase of the programme will receive $46 billion of Chinese assistance, some of it on commercial terms and some on concessional terms. The overall programme, in terms of its project-content, is still being defined. In Pakistan, the Planning Commission has the primary responsibility; it has a website that regularly updates to provide basic information on the programme. Initially, the programme was valued at $46 billion, but now the Pakistani officials have begun to mention a higher figure of $60 billion.

The alignment of the main corridor has been controversial from the time the programme was launched. Pakistan, in consultation with the authorities in China, has developed plans to build three corridors: the western alignment passing through the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, the eastern alignment passing through Karachi, Multan and Lahore, and the central alignment which is the shortest route but does not touch the most developed areas of the country. All these will bring different benefits to the various regions. The eastern corridor will link the Pakistani industrial base with China’s industries. In China, the industrial sector is being restructured to move out of low-wage activities into higher value production. The Chinese would like to see vertical integration with Pakistan’s manufacturing such as textiles and garments, surgical and sports goods, and leather products. The second route would pass through Pakistan’s agricultural heartland which can supply fruits and vegetables — fresh and processed — to the rapidly expanding cities in China’s west. The western part, which passes through the relatively unsettled parts of Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, will become China’s point of entry to the enormous mineral wealth of Afghanistan and Central Asia.

There are benefits to China from the implementation of the BRI. For instance, according to BHP Billiton, steel demand in the country is likely to increase by 150 million tons, doubling the rate of growth for the commodity. “BHP believes the demand for Chinese steel demand won’t crust until the middle of the 2020s, contrary to some analysts who have said it has hit its maximum.” This increase in demand will impact on iron ore prices that rose to record highs of close to $200 a ton several years ago, dropping to about $40 in 2015. This year prices have rallied to $95. BHP identifies 400 core projects within the scope of the BRI. Power, railways, pipelines and other transport projects make up 70 per cent of the total investment. The 68 BRI countries and regions covered by China’s ambitious plans are short of domestic steelmaking capacity. “Those projects could lead to an additional 15m tons of steel over 10 years, an additional three to four percent in demand growth on top of the current one per cent.”

At the Belt and Road Forum in May 2017, China presented the BRI not just as a development programme, but as a stimulus for trade in a world struggling with reviving lowered growth and stalling trade volumes. Given the new American president’s penchant for protectionism, China was pledging to work to lower trade barriers. Many of the countries it was working to bring into its economic orbit, needed better infrastructure and better trade relations. “There is the potential for it to do real good,” wrote the Financial Times in an editorial that was published as the world leaders were gathering for the summit to discuss the Chinese initiative. “Whether that potential is realised depends in large part on what China’s objectives are, and whether it pursues them with discipline. A great deal will depend on why and how projects are included in the programme. While they are being built, local and global businesses, not just Chinese ones, should get involved. Once built, they should be well utilised. “If these conditions are not met, it will be a clue that China, instead of contributing to global recovery, is trying to export its economic imbalances while buying regional leadership,” continued the newspaper. But all indications are that the Chinese have found a way of reconciling their national interests with those of the countries in which they are working on BRI projects. This is not the case, however, with the larger countries in the area.

One reason President Xi Jinping convened the Beijing Summit to formally launch the BRI was not only to explain the programme along with its socio-economic benefits, but was also to draw the attention of the larger countries in the area. Vladimir Putin, the Russian president, was given prime billing at the Beijing summit. In his address, the Russian leader said that Beijing’s initiative had many things in common with Moscow’s own regional initiative, the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). Eurasian integration he, said, “is a civilisational project for the future.” But there were informed voices in Russia that had apprehensions. “The most unpleasant issue for us is that China is becoming a serious centre for integration processes in Eurasia, which it never was in the past,” remarked Vladimir Portytakov, deputy director of the Institute of Far Eastern Studies at the Russian Academy of Sciences. “Instead of linking up the EEU and the Belt and Road, we may end up with the EEU being subordinated to this Chinese scheme.”

President Xi was responsive to these concerns. In 2015, he and President Putin had agreed to integrate the two economic spaces but subsequent discussions did not go very far. The Chinese leader was anxious to reassure the leaders that his programme would not disrupt other nations’ trade projects such as the EEU or Turkey’s “Middle Corridor” plan link up with other Turkish-speaking states.

India was another regional power that was concerned about the BRI. The Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, decided not to accept the Chinese invitation to attend the summit. The Indians had several objections, one of which was that part of the CPEC was being built in an area New Delhi believed was its territory. The CPEC would pass though the areas in northern Pakistan that India claimed was a part of its state of Kashmir. India also believed that connectivity projects must conform to international standards relating to good governance, financial responsibility, environmental and ecological protection, local community involvement, and local skill-building. It did not believe that the BRI was in line with these best practices. Further, it had its own connectivity projects whose interests would be harmed if Beijing put in more money than India could afford, to advance its regional initiatives.

How will Pakistan fare with the CPEC? Of particular concern is the enormous debt Pakistan is piling up on account of the implementation of the China-funded programme. The CPEC is a cluster of projects that will cost some $45 to $60 billion over a decade or so. This will be done with the support of various Chinese entities that will provide funding for the projects on commercial, semi-commercial, and grant terms.

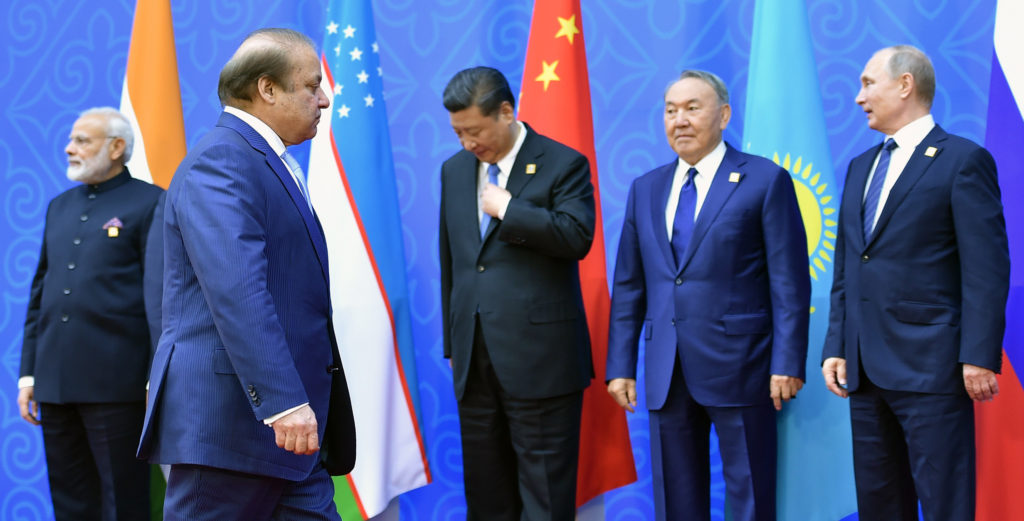

Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif arriving at the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) Summit in Astana

Most of the projects on which work has already begun were not carefully analysed with respect to their cost-benefit outcomes. It was assumed that the projects must have been carefully vetted by the Chinese entities that are financing them. Even if that is, indeed, the case, Chinese socio-economic interests may not perfectly match those of Pakistan. That said, if Chinese investments result in bumping Pakistan’s GDP growth to 7.2 per cent a year compared to the expected 5.7 per cent in about 10 years time, that would have added almost $85 billion to the country’s national output by 2030. I have built a scenario to estimate the rate at which the GDP will grow; I see it stabilising around 7.2 per cent a year by 2026, and staying at that level until 2030 when the servicing of part of the Chinese inflow, that has come in the form of loans, begins. The Chinese investment would have lifted Pakistan’s GDP to close to $700 billion; without it, it would be around $615 billion. If 30 per cent of the additional income is obtained by the government as tax and other revenues, that would bring an additional income of $25.5 billion into official coffers. This is more than what the government will need to pay back Beijing annually.