Boom Time Boys

By Nusrat Khawaja | Art Line | Published 8 years ago

The characteristic exuberance of Salman Toor’s style is in the full bloom of maturity in his third solo show at Canvas Gallery titled Short Stories.

The display is divided between 10 oil-on-canvas paintings and five “boom” cut-outs. The latter are made of MDF (medium-density fibre) board, and cut in the irregular jagged shape that symbolises punchy slang expressions in comic books and graphics, such as ‘boom,’ ‘pow’ and ‘wow.’ The boards are covered with a mess of scribbled notes written in Urdu that have been drafted with a green pen.

Two writers have been cited as muses for Toor’s Short Stories series of paintings. The master par excellence — Anton Chekov — and, closer to home, Daniyal Mueenuddin. The short story writer’s craft can focus on everyday commonalities and lift them from the banal to the sublime. Its pithy format is able to swiftly take a pebble and polish it into a gem. The burnished transmission of a moment, a thought or an event, that becomes a window to wider insights, characterises a great short story.

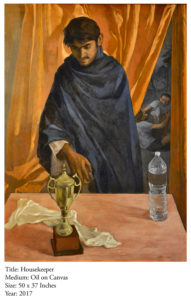

The revelatory possibilities inherent in the short story have been translated into painting by Salman Toor. Stories are being told through images with theatrical effect. The paintings have a sharply focused foreground where the main narrative is centred. The middle ground and background have softer edges and these receding planes become opportunities for additional vignettes of action to be included in the frame.

These narrative-rich paintings are allegories that reveal the dynamics of social behavior. The characters in the series are mostly male. There is a focus on the adolescent school boy in several canvases.

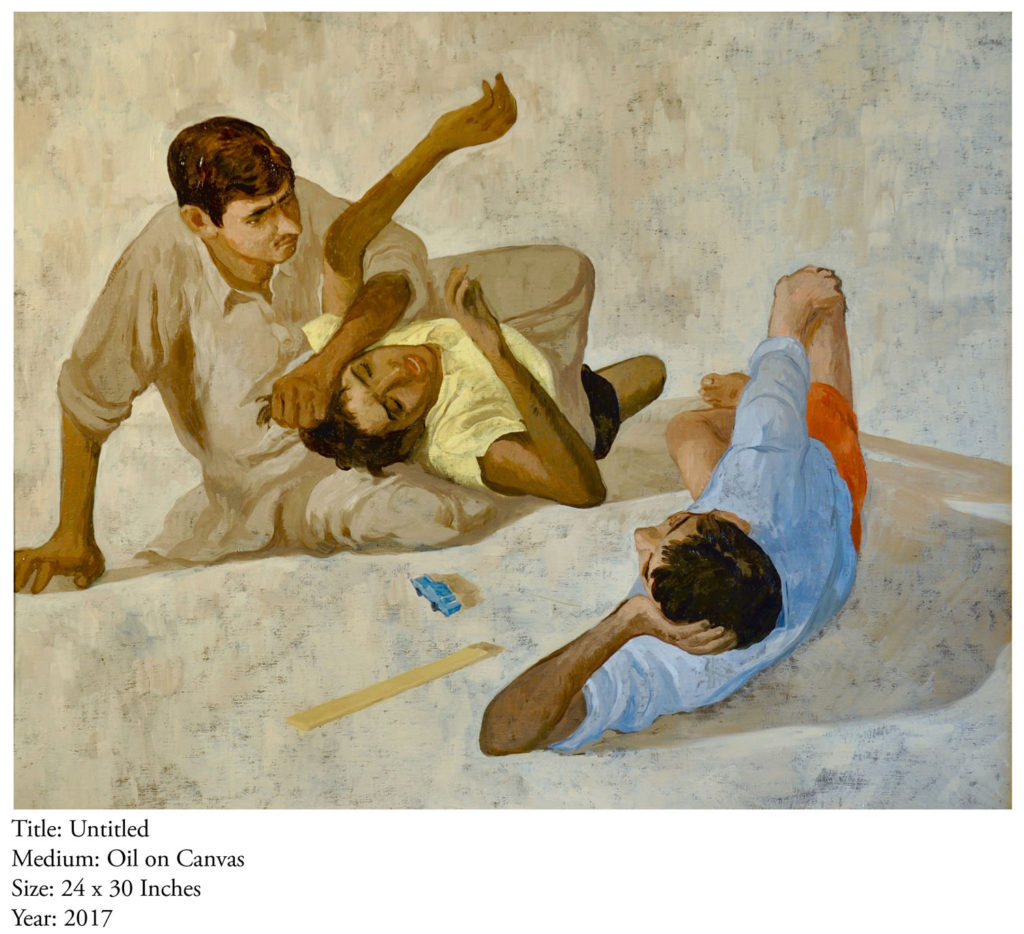

In ‘Playground’ and ‘Playground II,’ a schoolboy lies on the ground as he is being set upon by two other boys. There is a play of flailing and interlocking limbs, but in ‘Playground,’ the logic of the contortion of legs from torso is hard to follow with reference to the boy being beaten.

Toor says this composition of intertwined arms and legs was inspired by Classical Greek and Roman statuary. Certainly, we can see the template for oppositional tension of limbs and twisting of the body in statues such as ‘Hermaphroditus fighting the satyr’ (from the ‘Villa of Poppaea,’ now at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art).

The aggression portrayed in the two paintings mentioned above may be explained as a psychosexual release of burgeoning teenage hormones. But the narrative goes deeper than that. In both scenarios, there are clusters of two and three individuals positioned away from the main focus of action. These people chat in their own space completely unaware of the trouncing being administered to a young boy. The indifferent postures strike a commentary on the broader sociological response to bullying in our society.

In ‘Sleeping Maulvi, ’ the strands of the “short story” within the frame of the painting are set compositionally at a receding diagonal. The maulvi has fallen into deep sleep on a Louis VI style sofa. He is placed midway on the diagonal axis. At the far edge, a young man sprawls on the floor while a standing woman hovers above him trying to engage him.

In ‘Sleeping Maulvi, ’ the strands of the “short story” within the frame of the painting are set compositionally at a receding diagonal. The maulvi has fallen into deep sleep on a Louis VI style sofa. He is placed midway on the diagonal axis. At the far edge, a young man sprawls on the floor while a standing woman hovers above him trying to engage him.

At the right front edge of the diagonal axis, a Buddha-head and two vases holding pink rose stems sit atop a table. This vignette of serenity is a counterfoil to the deep oblivion of the napping maulvi and to the fraught pairing of the man and woman.

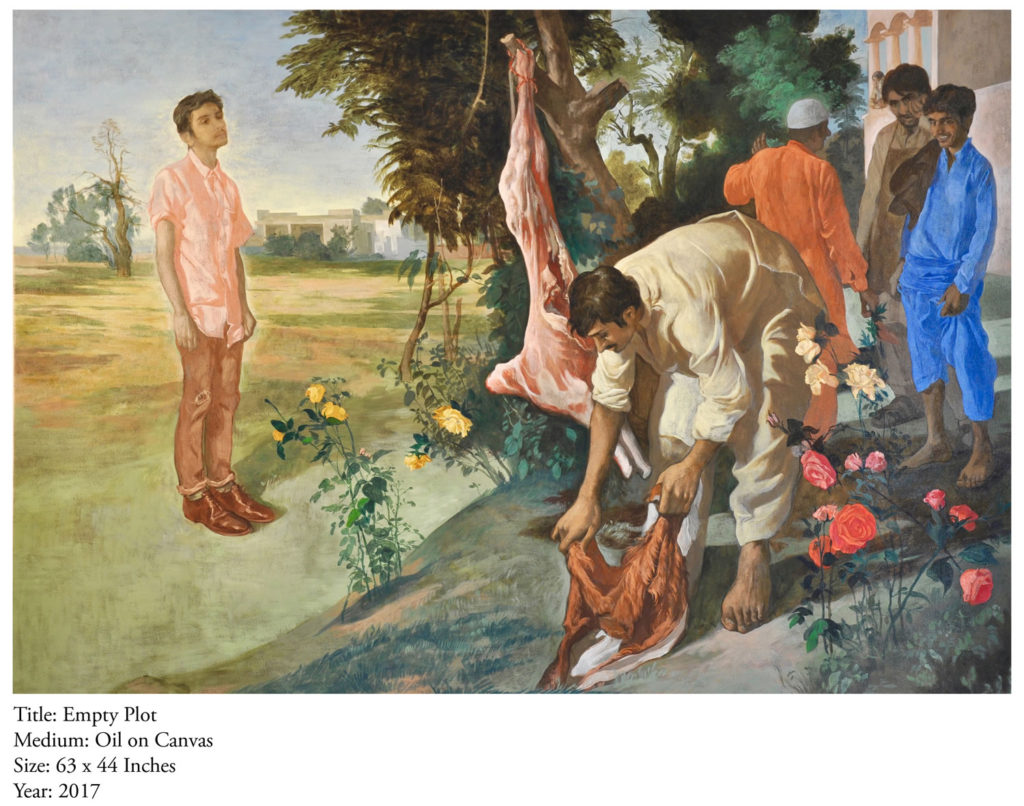

Roses recur in several paintings; as cut flowers placed in jars or as shrubs as in ‘The Empty Plot.’ Perhaps they are meant to draw attention to nature that has been cultivated by humans to enhance beauty even as the raw passion of human nature spills out uncontrollably. In our society a thin line is etched between prescribed behavior and its inevitable breach.

A strong sense of drama is inherent in Salman Toor’s work. The slightly exaggerated features on faces, such as the elongated Pinocchio-like noses coupled with scenes of skirmishes, leave a sense of made-up characters performing on a stage with painted backdrops. The “boom” boards, set among the paintings, create a somewhat discordant note because they contrast with the visual displays and disturb the illusion of theatre that the viewer is keen to participate in.

The two genres — painting and text — are visually disparate but connect them we must, for everything connects in the fecund mind of Salman Toor. The text panels are lifted from the artist’s notebook. They pin the title of the show to the literary foundations which underlie the inspiration that is manifest in the storytelling expressed by the powerful visual content of the paintings.