Celebrating Diversity

By Nudrat Kamal | Arts & Culture | Published 8 years ago

In all superhero origin stories, there is a moment, early on, when the main character decides to embrace her superpowers and use them to save people’s lives — it is the moment when she goes from being merely a person with superpowers to an actual superhero. The decision is motivated by various factors — an overpowering sense of justice, a need for self-improvement or absolution for past wrongs — and the superhero draws on different sources of inspiration, depending on who the superhero is and what their life is like. In the case of Kamala Khan, the teenage Pakistani-American headliner of the ongoing and massively popular Ms. Marvel comic book series, this life-altering decision draws from a source of inspiration unexpected in the world of superheroes and comic books: the Quran. When she comes across one of her classmates drowning, and is about to use her freshly acquired powers to save her, Kamala thinks, “There’s this ayah from the Quran that my Dad always quotes when he sees something bad on TV — a fire or a flood or a bombing. ‘Whoever kills one person, it is as if he has killed all of mankind, and whoever saves one person it is as if he has saved all of mankind.’” In the western media landscape, where most Muslim characters inevitably tend to have bombs strapped to their chests, Kamala’s reliance on her faith as a source of strength and courage feels particularly revolutionary, and it’s only one of the many reasons why Ms. Marvel has been, and continues to be, a breath of fresh air in the world of superheroes.

Created in 2014, this version of Ms. Marvel (the original Ms. Marvel was conceived in 1968 as a white woman, Carol Danvers, who now bears the mantle of Captain Marvel in the intricately populated Marvel Universe) is the brainchild of writer G. Willow Wilson (a white Muslim convert) and Marvel editor, Sana Amanat (a Pakistani-American herself). Launched amidst considerable hype due to its status as the first comic book series with a Muslim superhero headliner, Ms. Marvel has nevertheless managed to not only live up to the initial hype but to remain consistent in its high quality storytelling, thanks in no small part to Wilson’s confident and assured development of Kamala’s character, and the way she uses different aspects of Kamala’s identity — Muslim, daughter of South Asian immigrants, teenager — to give her superhero arc a unique specificity. In the four intervening years since the launch of the first issue, Ms. Marvel delves into Kamala’s journey of coming into her own as a superhero, becoming part of the larger Marvel superhero team and defeating supervillains, and learning how to balance her personal life with her secret life, all the while touching upon issues of racial profiling, Islamophobia, and what it means to be a young American growing up in an increasingly divided US. That the series manages to juggle all these different balls while maintaining carefully plotted narrative arcs, nuanced character development, and fresh writing that is full of humor and lots of heart, is a remarkable feat.

When the series begins, Kamala is a 16-year-old high schooler grappling with normal teenage issues: dealing with overbearing parents, hanging out with best friends, Nakia and Bruno, and trying to fit in with the popular crowd. But unlike Peter Parker, another teenage misfit who becomes a superhero (Spiderman, for the uninitiated), her inability to fit in is more racially and politically charged — in one of the first few pages, a popular girl at their school makes fun of Nakia’s hijab, commenting, “Your headscarf is so pretty, Kiki. But, I mean, nobody pressured you to start wearing it, right? I’m just concerned,” and jokes that Kamala “smells of curry.” But while Kamala feels ambivalent about the way her religious and racial identity marks her as an outsider, her faith is often drawn into her character development, something she quite organically reaches out for in times of doubt and difficulty. One of the most interesting scenes in the first arc is when Kamala’s parents, concerned with their daughter’s sneaking out at night and being secretive, send her to the imam of their mosque. Kamala isn’t very keen on discussing her secret superhero adventures with the imam, Sheikh Abdullah, who gives weekly religious lectures to the young Muslim population of Kamala’s neighbourhood in New Jersey. However, he surprises her (and the audience) when, upon learning that Kamala plans on carrying on with her secret plans, instead of berating her for hiding things from her parents, he gives her empowering advice. “If you insist on pursuing this thing you will not tell me about,” Sheikh Abdullah says, “do it with the qualities befitting an upright young woman: Courage, strength, honesty, compassion, and self-respect.” This scene is one of many in which religion is a positive influence in Kamala’s life, providing her with guidance and strength.

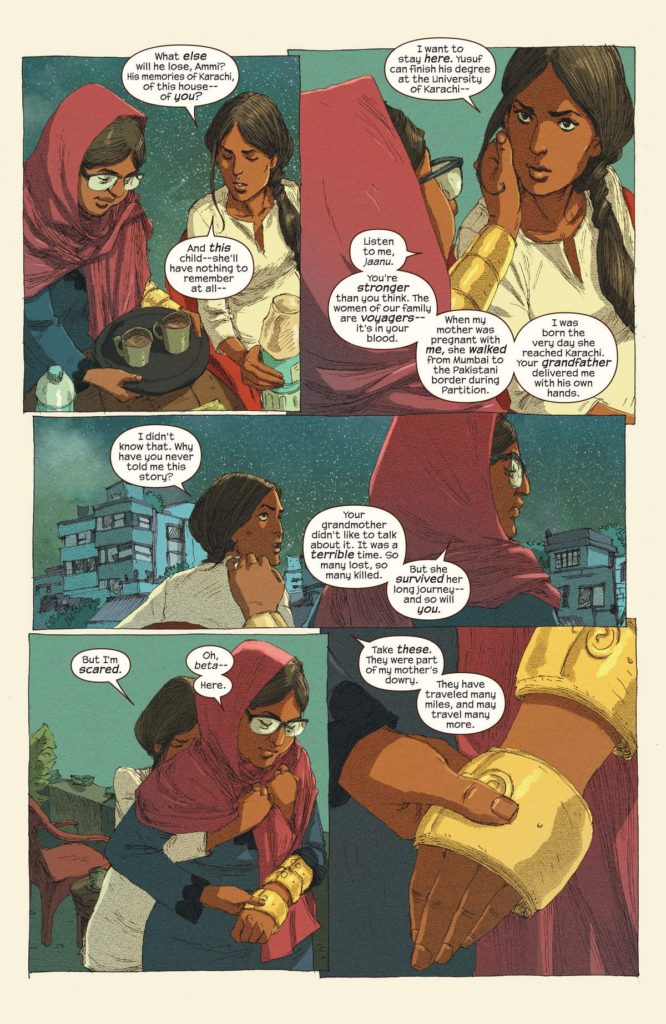

Just as Wilson organically incorporates Kamala’s Muslim identity within her larger superhero narrative, she also weaves in her South Asian heritage and her identity as the daughter of Pakistani immigrants with thoughtful specificity — the dialogue between Kamala and her family members are interspersed with Urdu sentences and phrases, and South Asian pop culture references (there is Amitabh Bachhan’s Sholay and Tagore’s poetry, to name just two) are casually dropped in a manner that feels authentic rather than forced. In one of the more recent issues, the South Asian Partition is explicitly brought into Kamala’s superhero origin backstory: Kamala’s grandparents’ harrowing journey from Bombay to Karachi in 1947 is paralleled with Kamala’s parents’ decision to move from Karachi to New Jersey right before Kamala is born, and both journeys, born of equal parts of hope, fear and courage, inform Kamala’s character and perspective when faced with her own challenges, as family histories undoubtedly do. The significance of Kamala’s family history is both metaphorical and tangible: the gold bangles Kamala’s grandmother brought with her to Karachi during Partition are handed down the generations until they become refashioned into an essential part of Kamala’s superhero costume. A fun recent story arc also shows Kamala visiting her maternal family in Karachi and taking down a villain with a local superhero named Lal Khanjar (even her costume gets a desi twist).

One of the best things about the Ms. Marvel series is how unabashedly optimistic and heartwarming it is, even when dealing with insurmountable threats, both fantastical and real. In that sense, it reflects Kamala’s own youthful idealism and passion, a kind of defiant hopefulness that embraces and celebrates the different aspects of Kamala’s identity, and in doing so, embraces and celebrates different kinds of diversity. Such a celebration of diverse values is sorely needed, not only in Trump’s America (unsurprisingly, Kamala Khan shows up in lots of anti-Trump protest signs and banners), but also in a larger world becoming increasingly fearful of difference.

Nudrat Kamal teaches comparative literature at university level, and writes on literature, film and culture.