Striking Gold

By Rahimullah Yusufzai | News & Politics | Published 14 years ago

A mutually beneficial relationship between militants and criminals has given a new and dangerous dimension to the lucrative business of kidnapping and resulted in a significant increase in such incidents.

A mutually beneficial relationship between militants and criminals has given a new and dangerous dimension to the lucrative business of kidnapping and resulted in a significant increase in such incidents.

Kidnapping for ransom has always been a lucrative business in parts of Pakistan but it seems the trade in human misery was never such a thriving industry. Many cases go unreported as families and employers, who, in many instances, happen to be from the government, quietly pay the money that is demanded by the kidnappers. Still, the incidents that are reported to the police are significant in number, and the figure keeps mounting.

The ideal place for kidnappers to operate in is the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) where Pakistani militants and their ‘guest’ fighters from other countries have found sanctuaries. The special status of FATA, which is geographically located in the NWFP but governed by the federal government through the provincial governor, has made it a ‘no-go’ area for the police and, therefore, beyond the reach of conventional law. In the process, FATA has, over the years, earned notoriety as a centre of the kidnapping business.

The Khyber Agency, in particular, is known as the abode of powerful gangs of kidnappers, operating mostly out of its Bara and Jamrud tehsils and the remote Tirah valley. The gun-manufacturing town of Darra Adam Khel, the Frontier regions of Bannu, Lakki Marwat and Jandola, and the tribal areas of North Waziristan, South Waziristan and Mohmand Agency too were known as hideouts for kidnappers and the ideal place for ‘safe-keeping’ of those kidnapped. The lack of government writ in FATA is the main reason for kidnappers to pursue their inhuman trade in the tribal agencies. The kidnapped persons could be easily shifted and kept in the tribal areas without the fear of being caught as the country’s police and courts don’t have any jurisdiction there. Though the security forces are now present in all seven tribal agencies and also in the semi-tribal Frontier Regions where military operations were conducted, their priority is to hunt down militants. Besides, some of the kidnappers’ gangs have set up networks in settled areas and established their hideouts in villages close to major cities like Peshawar. In fact, some of the kidnapped people are now being recovered from urban localities in Peshawar city. It is evident that these gangs are fearless and have spread their tentacles to urban areas apparently with the connivance of moles and accomplices in the law-enforcement agencies.

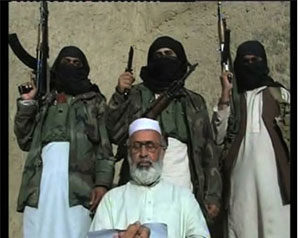

The dramatic rise in kidnappings is not only due to the deterioration in the law and order situation but also on account of the growing involvement of militants in the business. The militants kidnap people both for ransom and for securing the release of their colleagues who are in the custody of the government.

Kidnappings are now one of the major sources of income for certain militant factions, particularly the ones that have allowed criminals to join their ranks. The rise in the kidnapping of government officials and wealthy people is evidence of the fact that the militants are focusing on such crimes to raise money. Some militants’ commanders have conceded that they kidnap people to provide resources for waging ‘jihad’ against their enemies: Pakistan’s security forces and law-enforcement agencies. The willingness of the governments in Afghanistan, Pakistan and other troubled countries to make deals with the militants-cum-kidnappers and pay ransom to secure the release of the kidnapped persons has emboldened the militants and prompted them to organise more kidnappings, particularly of known and influential people.

It is true that kidnapping for ransom, or the related business of car lifting, is a fact of life in all provinces of the country. People are picked up everywhere and all the time and then shifted to places where the long arm of the law cannot reach them. Not long ago parts of interior Sindh became no-go areas due to the presence of major kidnapping gangs. Punjab, or for that matter the federal capital of Islamabad, aren’t immune from this menace. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan have always been recognised as happy hunting grounds for kidnappers, who find it easier to hide kidnapped persons there until ransom deals are struck with hapless families.

Dens of kidnappers also exist in some of the Provincially-Administered Tribal Areas (PATA) in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. One such PATA territory is the Malakand Agency, which is probably the biggest kidnapping centre in the province. Sakhakot, located in Malakand Agency, is home to at least four feared gangs of kidnappers. People are kidnapped frequently from the adjacent Mardan, Swabi, Charsadda, Nowshera and Peshawar districts and sometimes from Punjab and Sindh and brought to Sakhakot. It is a mystery why no proper action has been taken to date against the kidnappers operating out of Sakhakot, though common people often say that powerful interest groups involved in this crime offer protection to the criminals. Even in the tribal areas, the last time a tough operation was carried out against criminals was in late 1985, on the orders of then governor Lt Gen Fazle Haq when the houses of kidnappers and those running gambling dens and liquor shops in Jamrud and Bara were demolished.

Those aware of the workings of kidnappers’ gangs will tell you that in more than 90% of the cases ransom is paid to secure freedom for the hapless kidnappees. Huge amounts are paid to recover kidnapped persons belonging to resourceful families. So elaborate is the network of kidnappers that the gangs now perform specific jobs such as collecting information on potential victims, physically snatching the person, providing “safe-houses” for holding the kidnappees, establishing well-protected hideouts, renting out the kidnapped people, and negotiating ransom deals. A kidnapped person is sometimes sold and resold to different gangs and frequently shifted to avoid detection and recovery. Families ready to keep victims and provide them food and other amenities are paid for the services out of the ransom money. Occasionally, government officials and members of the law-enforcement agencies are known to have become part of the kidnapping rings when tempted by prospects of making easy money.

Quite often government employees such as those working for Wapda, Pakistan Telecommunication Company and the line departments are kidnapped in the southern districts of NWFP and taken to the tribal areas. Employees of pharmaceutical and mobile phone companies and doctors and engineers are also a favourite target of kidnappers as they or their employers are considered rich enough to pay huge amounts as ransom.

Gangs of kidnappers and militants now also operate across provinces and countries. Pakistani and Afghan militants and criminals have joined hands to ply their trade across the Pak-Afghan border. In Balochistan, a similar nexus reportedly exists between groups operating in Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan. Industrialist-turned-politician and former provincial minister Abadan Faridoun Abadan was kidnapped on February 17, 2002, in Balochistan, and shifted to the border areas of Iran-Pakistan.

The kidnapping of known persons and those linked to the government and security forces has become a matter of serious concern because militants not only receive ransom in such cases but also secure release of their men, including those considered dangerous and already convicted on charges of involvement in militancy and terrorism. The list of such high-profile kidnappings is long. Presently, Ajmal Khan, Vice Chancellor of Islamia College University, Peshawar, a cousin of the ruling Awami National Party head Asfandyar Wali Khan, is in the custody of kidnappers linked to the outlawed Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), which is demanding freedom for its detained fighters and ransom for his release. He was kidnapped from Peshawar in September 2010. A faction of the TTP operating in Darra Adamkhel and Khyber Agency had earlier kidnapped the Kohat University Vice Chancellor Dr Lutfullah Kakakhel and freed him after six months. The government had to pay Rs 50 million as ransom to the TTP and release several of its men. The late TTP founder Baitullah Mehsud had also used kidnappings, including those of Pakistan Army soldiers, to secure the release of his men — and his successor is following in his footsteps.

The militants are also holding a former Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) officer, Colonel (retd) Imam, and refusing to release him until their demands are met. British journalist Asad Qureshi, who is of Pakistani origin and had accompanied Col Imam when they were kidnapped in North Waziristan, was recently freed after payment of ransom. Another former ISI official Khalid Khwaja, who had also accompanied them, was shot dead by the militants.

Diplomats are highly prized by the militants-cum-kidnappers. Abdul Khaliq Farahi, Afghanistan’s ambassador-designate for Pakistan, kidnapped from Peshawar, was recently released after two years following payment of an unspecified amount as ransom and possibly the release of some captured militants. Iranian diplomat Hashmatullah Attarzadeh, who too was seized by kidnappers in Peshawar, was freed some months ago after an undisclosed deal. The release of Tariq Azizuddin, Pakistan’s ambassador in Afghanistan also became possible after seven months following a deal with the militants, even though Interior Minister Rehman Malik claimed that he was freed after an operation by the security and law-enforcement agencies. Some Chinese engineers, too, were kidnapped by the Swat Taliban and freed after a deal, whereby militants were released and ransom was paid. One Chinese engineer kidnapped some years ago by the Pakistani Taliban commander Abdullah Mehsud, and a Polish engineer were not that lucky as the former was killed during a rescue mission and the latter was beheaded by the militants because their demand for ransom and release of their men wasn’t conceded.

Sometimes, the militants kidnap people on the basis of wrong information, but still get paid even if the ransom amount is less than what they demand. This happened recently in the case of one Muhammad Hussain belonging to Multan who was freed after 10 months in captivity. According to newspaper reports, he was trapped by his former classmate hailing from North Waziristan and kidnapped by the TTP, which was given to believe that he was a nephew of Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani. The TTP men demanded Rs 200 million as ransom for his release, but had to settle for Rs 3 million only when they realised he was no relation of the Prime Minister.

Rahimullah Yusufzai is a Peshawar-based senior journalist who covers events in the NWFP, FATA, Balochistan and Afghanistan. His work appears in the Pakistani and international media. He has also contributed chapters to books on the region.