Redefining Myth

By Nusrat Khawaja | Books | Published 8 years ago

The beginnings of all stories are founded in myth. The archetypal qualities of foundation myths ensure that civilisations and cultures can delve continually into mythical content and re-emerge with a refreshed cosmic perspective. Mythical narrative is a regenerative spring which never runs dry and it bestows literature with incredible poignancy.

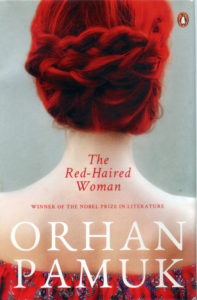

Orhan Pamuk, the master storyteller from Istanbul, draws upon two foundation myths from West and East in his tenth novel, The Red-Haired Woman. The dual borrowing bears resonance with the location of Istanbul, sitting as the city does on the cusp of Europe and Asia. But more profoundly, the book explores the error of human judgement as it negotiates the dichotomy between the known and the unknown.

From Greek mythology there is the story of Oedipus, who unknowingly murdered his father and married his own mother. From Persian legend there is the story of Rustam and Sohrab, in which Rustam unknowingly kills his son Sohrab on the battlefield.

This dichotomy between the known and the unknown is integral to both tragedies, as is the father-son relationship. Pamuk reworks these themes into a novel set in contemporary times. The Red-Haired Woman is divided into three parts. The protagonist of the novel is Cem Celik [pronounced Jem Chelik]. Parts one and two are told in his voice.

The story opens when Cem is 16, with aspirations to become a writer. But during the summer school break, Cem’s enigmatic father, with left-wing inclinations, disappears, forcing his wife and child to move in with an aunt and her husband.

While Cem is guarding the cherry and peach orchards that belong to his aunt’s husband, he is drawn to the efforts of a master well-digger who has discovered water. Master Mahmut, the esteemed well-digger, invites Cem to apprentice with him at a dig he is about to commence upon near a town called Ongeren, just outside Istanbul. Cem is a “bourgeois,” but accepts this laborious assignment with the hope of saving enough money to pay for cram school and gain admission to university.

Master Mahmut becomes a surrogate father to Cem during their days of relentless labour and nights of rest under the star-spangled sky. Cem regularly visits the town of Ongeren for supplies and is drawn to a travelling theatre troupe, ‘The Theater of Morality Tales,’ whose performances include scenes from Rustam and Sohrab. The female lead is an attractive, red-haired woman with whom Cem becomes deeply infatuated.

Forces of destiny are at play during this unusual interlude in Cem’s life as a manual worker. He causes an accident and escapes from Ongeren carrying a huge burden of guilt. In the second part of the novel, Cem transitions to adulthood with repressed guilt. He says: “If I ignored the guilt, the darkness inside me, I thought I would eventually forget it was there.” It is only in the third part of the novel — which is a testimony spoken by the red-haired woman — that the unclear aspects of the storyline become flawlessly intelligible.

This beautiful novel is translated in clear and simple prose by Ekin Oklap, which allows the complex issues presented within to emerge with clarity. The psychological tension points, especially pertaining to the father-son relationship, are exquisitely nuanced.

Symbolism plays an important part in this book. The varying seams of earth that “seem to come from another world altogether” as Cem’s well grows deeper, bear parallels with the layers of myth and the layers of the human psyche. The well-digger, with his shaman-like ability to sense where underground water may be found, is not unlike a storyteller who infinitely reshapes human experience to yield stories.

Pamuk uses colour almost as an autosuggestive device by boldly titling this novel after the red-haired woman. The implications of colour symbolism are mnemonic; he has similarly used the colour red in My Name is Red and the colour white in Snow.

The references to myth run throughout the novel in different forms, starting with the three quotations in the epigraph from Nietzsche, Sophocles and Ferdowsi. It continues in the storytelling by Cem, the theatre performance in Ongeren, and in the books and paintings sought out by the adult Cem. But Orhan Pamuk has introduced an ingenious twist to the classical myths featured in The Red-Haired Woman. He has replaced the mythical hero of grand stature (such as Oedipus and Rustam) by the modern protagonist of our times: the antihero.

Cem Celik is the hinge connecting the grand themes of patricide and filicide. These themes transmute into a credible realism as the novel narrates the trajectory of Cem’s life, as lived in modern day Turkey. The novel may also be read as a bildungsroman (coming-of-age story) in which the error of youth carries into adulthood in a slowly unfolding but inevitable confrontation with Destiny.