Paradise Revisited

By Nusrat Khawaja | Arts & Culture | Published 8 years ago

Every place exists as a geographical entity as well as an idea. As geography, Kashmir is nestled in the Himalayan ranges and its modern borders are contested space. As idea, its verdant landscapes have assured it a comparison with an earthly Paradise. It is this notion of a Paradise that is highlighted by the display of artefacts of Kashmiri high culture in the exhibition at Mohatta, titled: Paradise on Earth.

Despite Kashmir’s lofty location encircled by mountains (a cart road opened from Rawalpindi to Baramula as late as 1890), cut off from access by winter snowfalls, it was occupied by a succession of foreign rulers, including Mughals, Afghans and Sikhs. The Emperor Akbar visited the valley three times and his son Jahangir laid out pleasure gardens along Dal Lake.

In this thoughtfully curated exhibition by Nasreen Askari (who is also the Museum Director) and Fatima Quraishi, the idea of Kashmir as a confluence of multiple cultural influences is delivered effectively. Care has also been taken to showcase the finest example of each craft.

The spirit of Kashmiri culture, as conveyed by the collection of illuminated Qurans, manuscripts, embellished crafts and miniature paintings, pre-dates the creation of the nation-states of India and Pakistan. Walking into Gallery 3 at Mohatta Palace feels like entering a sacred grove that distances one from the turbulence of current realities. Large information panels — as red as the cherries grown in the Kashmir Valley — provide context to the objects along with a helpful timeline of Kashmiri history.

The objects on display come from private collections and from the National Museum in Karachi. They are expressions of courtly culture.

There are traditional objects such as the voluminous Kashmiri robe (phiran) with embroidered neckline. Its width would easily enclose the portable body warmer — the kanger — which Kashmiris would fill with coal and carry under the robe to keep warm. There is a beautiful silver kashkol (begging bowl) with its traditional boat shape. The metal is repoussed with a floral pattern, a filigree edge and the pointed corners are finished with stylised animal heads.

These traditional crafts are closely linked to the valley culture of Jammu. However, the gorgeous manuscripts and miniatures on display manifest the absorption of wider influences from North India, Central Asia and Iran.

The curatorial notes mention the earliest written source of Kashmiri history which was a legendary chronicle of ruling dynasties of the region called the Rajatarangini (The River of Kings). This important manuscript was written by a poet named Kalhanna in the twelfth century. It was lost for many years and the quest for its rediscovery was undertaken by the scholar Aurel Stein in the late nineteenth century.

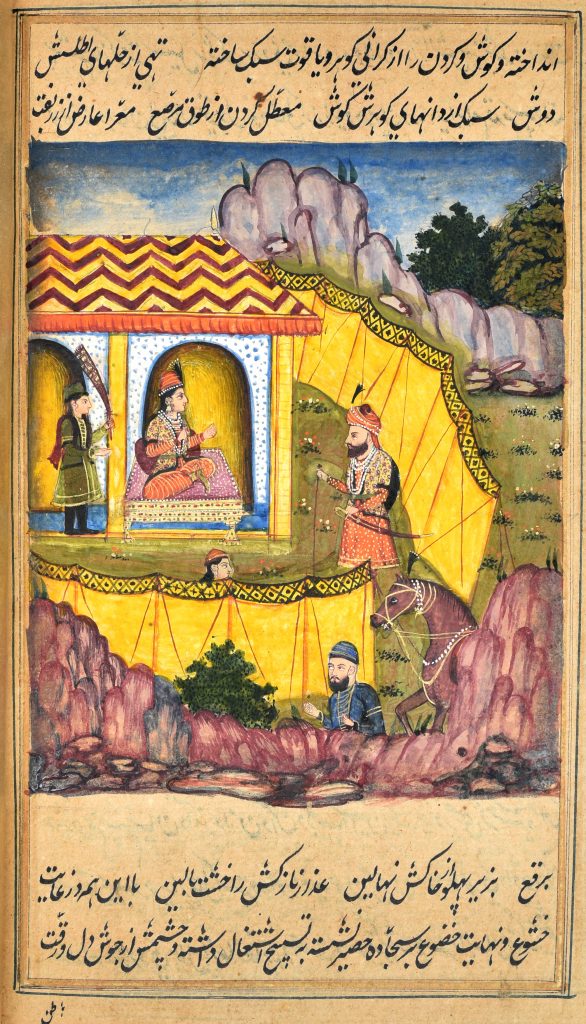

Although this important manuscript is not part of the exhibition, there are several other histories of Kashmir on display. Hand-written manuscripts of eighteenth century Tarikhs by Narayan Kaul Ajiz and Muhammad Azam Deedmari are a testament to the highly developed sense of Kashmiri identity. Moreover, this identity is based on inclusiveness of cultural influences from the wider Indo-Iranian cultural sphere. There are copies of Ferdowsi’s Shahname, Hafez’ Divan, Nizami’s Khamsa, Yusuf and Zuleikha and Layla Majnun.

Kashmir had been an important centre of Hinduism, Buddhism and Shaivism. Shah Mir became the first Muslim ruler of Kashmir in 1339. His dynasty ruled till 1556, when Kashmir came under the rule of the Mughals. Over these centuries of Muslim rule, Islam was consolidated in the region with a strong influence of Sufism.

The influence of Sufi saints may be gleaned from texts and illustrations. Sheikh Jazuli was a sixteenth century Berber Sufi who rose to prominence in Morocco. He compiled a popular prayer book called Dala’il al-Khayrat (A Guide to Good Deeds). A nineteenth century copy of this book is on display and it contains illustrations of sacred sites in Mecca and Madinah.

The curators of Paradise on Earth have drawn attention to the syncretism of religious practise in Kashmir by the inclusion of some exquisite Rajasthani miniatures, all on loan from the National Museum in Karachi. The miniatures come from different centres of production in Rajasthan, including Basohli, Chamba and Mandi. The one of Kings Suratha and Samadhi taking leave of the rishi Medhas is from the Markandeya Purana series, which was known for its non-sectarian mysticism.

The exhibition is intended as “a tribute to the people of Kashmir who, despite continuing hardship and turmoil, show courage and resilience in sustaining their artistic traditions.” Arguably, the message of eclecticism and tolerance so eroded in the region, still lives on through the paradisiacal space created by art.