“It’s the human interest stories that made it for me.” – Shrabani Basu

By Muneeza Shamsie | April issue 2017 | Books | Entertainment | Interview | Literature | Published 8 years ago

Shrabani Basu is a Calcutta-born, London-based journalist and historian, and the author of four critically acclaimed books, Curry in The Crown: The Story of Britain’s Favourite Dish (1999); Spy Princess: The Life of Noor Inayat Khan (2006); Victoria and Abdul: The True Story of Queen Victoria’s Closest Confidante (2010), and For King and Another Country: Indian Soldiers on the Western Front 1914-1918 (2014). All her books have brought to public notice a completely new aspect to the subjects they have focused on and highlighted the forgotten narratives of history. Spy Princess led to the Noor Inayat Memorial Trust and a statue, unveiled by Princess Anne in 2012, of the World War II heroine Noor Inayat in Gordon Square, London. Victoria and Abdul provided new insights into Queen Victoria and the confidence she reposed in her Indian Munshi, Abdul Karim — who also taught her Urdu — and is being made into a film starring Judi Dench as Queen Victoria.

Shrabani Basu is a Calcutta-born, London-based journalist and historian, and the author of four critically acclaimed books, Curry in The Crown: The Story of Britain’s Favourite Dish (1999); Spy Princess: The Life of Noor Inayat Khan (2006); Victoria and Abdul: The True Story of Queen Victoria’s Closest Confidante (2010), and For King and Another Country: Indian Soldiers on the Western Front 1914-1918 (2014). All her books have brought to public notice a completely new aspect to the subjects they have focused on and highlighted the forgotten narratives of history. Spy Princess led to the Noor Inayat Memorial Trust and a statue, unveiled by Princess Anne in 2012, of the World War II heroine Noor Inayat in Gordon Square, London. Victoria and Abdul provided new insights into Queen Victoria and the confidence she reposed in her Indian Munshi, Abdul Karim — who also taught her Urdu — and is being made into a film starring Judi Dench as Queen Victoria.

The daughter of a diplomat, Basu grew up in Delhi, Dhaka and Kathmandu and moved to England in 1987. She made her first trip to Karachi, after a member of Munshi Abdul Karim’s family learnt of her book and told her that his diary was in the possession of his descendants who had migrated to Karachi. The discovery led to a revised version of her book. This February, sponsored by the British Council, she came to Karachi again — for the literature festival which she greatly enjoyed and said, “it has a fantastic buzz.” She added that she has always been made to feel very welcome in Pakistan and pointed out, “My books are all set in undivided India, and to me the commonality of our cultures and history is what is important.” In this interview, conducted during the Karachi Literature Festival, she spoke to Newsline about her work.

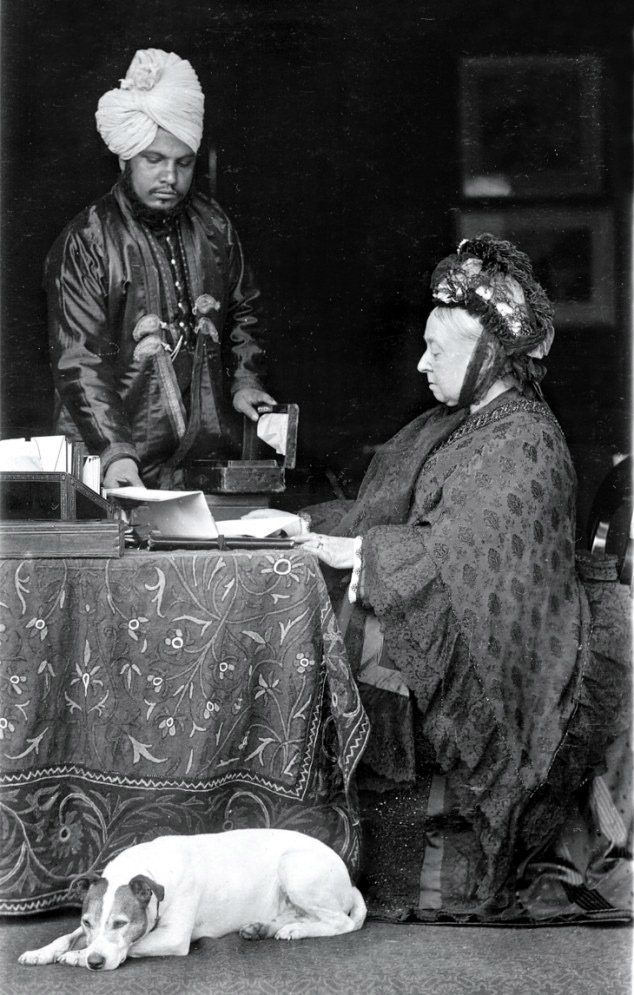

Queen Victoria at her desk, assisted by her servant Abdul Karim

What led to your interest in the story of Queen Victoria and Munshi Abdul Karim?

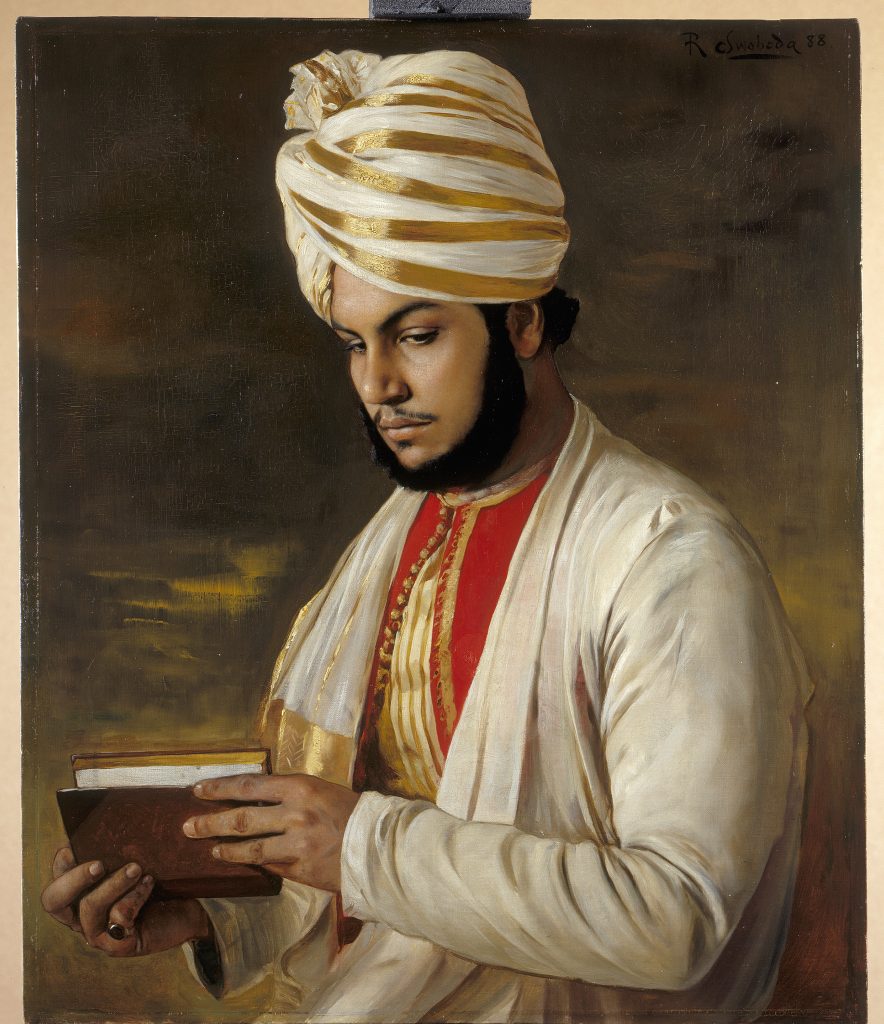

I knew that Queen Victoria had some Indian servants working for her and thought I would look it up. I went to Osborne House, which was her weekend retreat. And there she had made this Indian Durbar and in the Indian corridor were all these portraits of Indians that she had commissioned. One of them was of Abdul Karim. He was painted to look, not like a servant, but a Nawab. That portrait told me a lot. I thought this man was not just a servant. He was much more than that. So I went to the Royal Archives, to see what I could find.

In your book you describe how Queen Victoria’s household and her family hated the Munshi so much that they had all her letters to him destroyed, after she died. What alternative sources did you explore?

Yes, the first thing I learnt was that all the letters she wrote to him were burnt. I had to piece together the story through the diaries of the Royal Household, letters from the Viceroy — and finally, the icing on the cake was that I found Abdul Karim’s lost diary. That just completed the whole picture for me. It was amazing. I also went to his house in Agra. I found his grave. After Partition, his entire family had moved to Karachi, carrying this one diary, which I think is brilliant. No one had seen it. It was just lying in the trunk. Till I opened it — and there it was. All that familiar story came back to me. I stayed with the family in Karachi and I read the diary in their house. It was a wonderful experience.

Portrait of Abdul Karim

What did the diary reveal?

Well, many inside details. Some of the letters [from Queen Victoria] that he had copied were there. Plus his account — this was his voice, telling you what he reads, what he felt when he went there. There was an innocence about him when he went there. And the household hated him and I could see how racist they were — we do know this — but he never mentions this or how nasty they were to him. He kept it to himself. He died with this. It was great to be able to fill out his story.

Did your book take a direction that was unexpected?

Totally. When I started I had this image of Queen Victoria as being a very dour lady with no sense of humour, dressed in black representing Empire and all the symbols one associates with it. As I researched it, I found she felt very close to India, loved India, though she could never travel there. She was way ahead of her times. She hated racism. She put out a lot of memos that they should not be racist to Indians. She did everything she could to make the Indians comfortable and she learnt Urdu.

I believe she left behind all these journals written in Urdu?

She told Abdul Karim to teach her Urdu. That is how they became really close. She would never miss a lesson, whether they were travelling in a ship or by train. Even if Abdul Karim was ill, she would carry these boxes to his house, prop up his pillows, soothe his forehead, then she would take up her ‘Hindustani lessons’ — as they used to call it. So there were 13 years of them being together and 13 volumes of her Hindustani journals. These were a big plus for my story as well. Nobody had seen them. Nobody had opened them.

You see Queen Victoria’s English biographers would never be able to understand those. And they never touched them nor asked for them. They were lying there in the Royal Archives. They gave them to me as soon as I asked for them. I had them translated, because I can’t read Urdu either. And I gave them the translations.

How did your research change your perceptions of the Munshi?

I started out by reading a few biographies of Queen Victoria, written by western historians. In those he’s mentioned because he was an important person, but he is mentioned as a rogue, a bit of a Rasputin who wormed his way up. When I started researching I found that a lot had been lost in translation and a lot of it was really racist. I realised he wasn’t a rogue. I saw him as a young man who had come to this court, not because he asked to come but because he was invited. Within a few weeks he says, ‘I am not a servant.’ He was not a servant back home. He was a clerk in Agra jail. He didn’t like doing menial work and he wanted to go back. He was just 24 years old. The Queen begged him to stay. And that letter was in his journal, which I found very important.

Can you tell us about the film?

Can you tell us about the film?

The film is in production right now. The director is Stephen Frears, the script is by Lee Hall and the icing on the cake was Judy Dench, in the role of Queen Victoria. The Munshi is being played by a young Bollywood actor, Ali Fazal. I look forward to seeing it on screen.

What led you to Spy Princess, based on the life of Noor Inayat Khan?

Noor Inayat was the daughter of an American mother and an Indian Sufi descended from Tipu Sultan. She was brought up in France, recruited as a British secret agent and captured, tortured and killed by the Nazis at Dachau in 1944. But there was very little known about her, unlike war heroines such as Violette Szabo and Odette Harris. The 50th anniversary of the end of the Second World War was coming up. As a journalist I was covering Indian soldiers and there were all these veterans still in Southall. Then I came upon a little write up on Noor Inayat. Three lines. But it had her photograph and immediately attracted me because she was a woman. I was immediately drawn to her. What was she doing there during the war? How did she die?

The timing is important. In 2003, the British Government declassified records of secret agents. That was a start. Then I found her family. I spoke to them and pieced her story together through files on other agents. I met war veterans — women in the RAF (Royal Air Force) and secret services — who had worked with her and were still alive.

Noor Inayat, the Spy Princess

There was a book called Madeleine by Jean Overton Fuller about Noor, who was code-named Madeleine. Did it influence your work?

Madeleine was written much before and is full of inaccuracies, but I met Jean. As Noor Inayat’s friend, she became a part of my book, as a character there. She knew Noor. Her memory was intact. But she didn’t have access to files, because they weren’t declassified at the time.

What did the declassified documents reveal?

Everything. How Noor was recruited. How she feels. Why she joins. There are so many letters written by her. Her training records are all there. It was important to tell her story once the files came out.

What led to the Noor Inayat Memorial Trust and its campaign for a statue?

What led to the Noor Inayat Memorial Trust and its campaign for a statue?

Spy Princess caught the public imagination. And I got so many letters thanking me for bringing this story to life. Then people started saying we need a memorial for her. Many of her colleagues had blue plaques and memorials. And Noor had nothing, although she was one of three women, along with Violette Szabo and Odette Harris, to be awarded the George Cross. There was not even a photograph of her in the Imperial War Museum, where they have a room for winners of the George Cross and the Victoria Cross.

So I applied for a plaque for her but it was rejected on very flimsy grounds. That really upset me. Then I set up a Noor Inayat Memorial Trust. We campaigned for two years. We raised the funds. We had the memorial.

Then the Royal Mail brought out a stamp for Noor’s centenary. Now the Trust has started a prize, The  Noor Inayat Khan Dissertation, for an MA student at SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies), University of London. We wanted to make Noor’s message relevant to contemporary audiences and young students. Noor was fighting against fascism and for freedom. Her message is even more relevant now in the times that we live in.

Noor Inayat Khan Dissertation, for an MA student at SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies), University of London. We wanted to make Noor’s message relevant to contemporary audiences and young students. Noor was fighting against fascism and for freedom. Her message is even more relevant now in the times that we live in.

SOAS have now begun a Noor Inayat Khan Lecture series. I decided to call it the Liberté Series, because when Noor was killed in Dachau, her last word was “Liberté!”.

Can you tell us about your World War I book, For King and Another Country?

The Centenary of the First World War was coming up in 2014 and I knew that, once again, Indians were not going to be written about. One-and-a-half million Indians fought in the trenches on the western front, holding the lines against the Germans. Nobody knows about them. So I followed the lives of some soldiers who went from the hills of Garwhal and from places such as the North West Frontier. Khudadad Khan was the first Indian soldier to get the Victoria Cross. Then I have a Maharaja of Bikaner who went as well. I call them the ‘Band of Brothers’ — from the Maharajah to this untouchable cleaner, Sukha from Bareilly, who doesn’t even have a surname. It’s the human interest stories which made it for me. I am not a military historian.

Actor Ali Fazal on the film set

What next?

I have something in mind. I want to do something lighter. At the moment there is the excitement of the film Victoria and Abdul.