1971: The Official or the Actual?

By I. A. Rehman | Bookmark | Published 8 years ago

All those who believe that Pakistan’s political leadership has not learnt any lessons from the state’s  dismemberment in 1971, will find plenty of material in Rao Farman Ali’s book, How Pakistan Got Divided, to reinforce their argument.

dismemberment in 1971, will find plenty of material in Rao Farman Ali’s book, How Pakistan Got Divided, to reinforce their argument.

The first edition of this book was published in 1992, and its Urdu version appeared in 1999. The author’s children say they have prepared the present edition in order to clear the name of those officers and men of the Pakistan army, who have not only been denied credit for bravely fighting against heavy odds but have in fact have been held responsible for all the excesses that were allegedly committed and for everything that went wrong in East Bengal in 1971. While they are able to prove a part of their claim, that many of the troops fought bravely, regarding the rest of their contention, history alone can offer a final verdict.

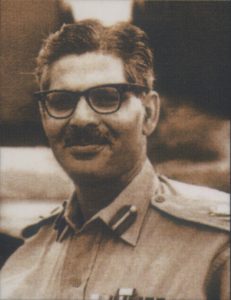

However, General Farman Ali’s account is still relevant and immensely valuable for many reasons. He was the most important long-time witness to the developments in East Pakistan, having served there in key positions during 1967-71. In fact, he had drafted the eastern wing’s original defence plans that were irrationally abandoned. As advisor to the Governor in 1971, he attracted adverse notices for sending a critical signal to the UN to intervene and for committing atrocities against the local population, but he was absolved of all such charges by the army’s scrutiny board and, more importantly, by the Hamoodur Rahman Commission. All those who were surprised at his rehabilitation after his return from the POW camp in 1974 may see the reason behind that.

A considerably significant part of the book is the preface in which the author answers some of the most commonly asked questions about the 1971 disaster. His explanation for the East Bengal people’s alienation from Pakistan includes nearly all the widely shared causes of discord. He asserts that a political solution of the crisis was possible. “The 1970 election was a political solution itself,” he says,” if the results had been accepted. Unfortunately, the two majority leaders of East and West Pakistan did what they felt was best for them; not what was best for Pakistan .”

Rao Farman Ali thinks military action was not absolutely necessary. He blames the West Pakistan leadership for creating “an environment that led to East Pakistan’s confrontation with the army.” He is quite emphatic in attributing the army’s military defeat to the national political leadership’s ineptitude. For the atrocities committed in March 1971, he holds both sides responsible and wants both of them to apologise to each other. In his view, the ignominy of surrender could have been avoided by accepting a ceasefire earlier. Finally, the author denies all the charges against him. However, the clearance given to him by the Hamoodur Rahman Commission on this is a far weightier testimonial than his own.

The younger students of the subject will find quite a few disclosures in the book. For instance, Rao Farman Ali’s report on the 1965 war was shelved because “it was critical of the ‘conduct of war’ and had concluded that we failed to achieve our aim — activation of the Kashmir issue — and thus had not won the war.” During the 1970 election, the Yahya regime did fund the Islam-pasand parties through some industrialists “but as the amounts were meagre and the parties too many, the effort had no impact.” The author confirms that the seeds of Pakistan’s disintegration were sown when the meeting of the National Assembly, scheduled for March 3, 1971, was postponed and General Yahya Khan failed to announce a new date in time. And the shameful haggle over allocation of seats for the by-elections to the National Assembly was simply sickening.

Rao Farman knew how to get round the politicians. When Sheikh Mujib-ur-Rehman pointed out to him his activities against the Awami League during the elections, his reply was: “I was trying to help him [Mujib] because with a big majority, he would find himself a slave in the hands of the extremists.” And, the author notes, this is what eventually happened.

The author claims that he repeatedly urged Yahya not to take military action in East Pakistan. He also asked General Omar to persuade Yahya to drop the military option and the latter promised to do what he could. But later on, General Omar “personally told me that, had it not been for him, Yahya would not have taken military action.”

A significant fact that emerges from General Farman Ali’s account is that if he was able to see Mujib whenever he wanted and could drive to his house in a small car, the possibilities of talking to the Awami League were always there. So why didn’t anyone seize the opportunity to engage with the Awami League chief.

What happened in the final days of the East Pakistan crisis has often been described in detail but it needs to be gone over, again and again, because it reminds us of the need to avoid reliance on lies and chicanery. The Eastern Command had lost the will to resist, but it was forced to continue offering sacrifices with lies that were doled out about Chinese and American intervention having begun. Besides, General Niazi continued to boast about defending Dhaka, although he neither had any plan nor the means for the mammoth task at hand.

While the book enables the readers to meet General Farman Ali as the straightforward fighter from Kalanaur that he wished to be taken for, the fact remains that he did not choose the course adopted by Admiral Ahsan and General Yaqub Khan. More importantly, his premises are not far removed from the flawed official narrative about the basic differences between the people of Pakistan’s two wings and the machinations of hostile elements. It is not easy to concede that the rot did not begin in 1967-1971; it began much earlier — perhaps on the morrow of independence.

Mr. I.A. Rehman is a writer and activist living in Pakistan. He is the secretary general of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan Secretariat.