The Final Note

By Sher Alam Shinwari | Music | Published 8 years ago

Zarsanga

The great Pashto poet and sculptor, Ghani Khan, had once said, “Pashtuns love music, but hate musicians.” This holds true to the extent that derogatory words like ‘dam’ and ‘shahkhel’ are still used for musicians and singers in Pashtun society. They are considered social outcasts and having ties with the artistes’ community is frowned upon. Musicians’ marriages are solemnised on the condition that they give up their profession forever. Most female Pashto folk singers give up performing after marriage, fading into obscurity.

According to the popular folk singer Zarsanga, female performers are worse off. Social taboos aside, they lack security and the opportunity to promote their work. She said that women singers and performers live in constant fear of being attacked. A few months ago, she and members of her family were severely beaten by their distant relatives over a family dispute. The concerned officials didn’t take care of them as was their due right. “The problem with the artistes’ community in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) is not finance, but the attitude of people towards them,” says Zarsanga. “Unless that changes, artistes will continue to suffer.”

Musicians and singers are excluded from the social hierarchy, remaining confined to their ghettos. Miangul Jahan Zeb (1908—1987), ruler of Swat was known, however, to award official status to musicians and singers living in his territory. They continue to reside in Mingora’s 200-year-old music street. Miangul had, in fact, married a girl from the music street.

However, the marriages of most women from the performing arts into wealthy homes turn out to be bitter experiences. They are not given respect and their due share in property.

Qamar Jan, a noted Pashto folk singer from the Mardan district, once confided in me that she preferred to remain unmarried after seeing what her sister went through in her marriage to a local Khan, who imprisoned and tortured her. Eventually, the sister succumbed to her injuries.

Locals still tell stories of the terror perpetrated by clerics in the pre-Partition era on artistes in the music street of Peshawar — then known as Dabgari Bazaar. However, the reign of Muttahida Majlis-i-Amal (MMA) — an alliance of nine religious parties — from 2002 to 2007, proved to be the darkest period in its history. All kinds of cultural activities came to a halt in KP. Musicians and singers starved, while those who could afford to do so moved to other cities or the Gulf. Many, however, were stranded in KP with no hope of betterment in sight.

The MMA imposed a complete ban on playing music in public places, shutters were lowered on Peshawar’s only theatre — Nishtar Hall — and Dabgari Bazaar was forcibly evacuated. Artistes were threatened, beaten, and told to quit their profession. Most Afghan performers returned to Kabul, while a few relocated to dark corners of Peshawar. The cinema halls around Peshawar were soon deserted and even signboards displaying images of women faced the wrath of MMA supporters.

Adding fuel to the fire, Swat militants took over and targeted the music street. Shabana, a famous dancer, was brutally killed in Swat. Her murder sent shockwaves across the artistes’ community. The militants’ crackdown was well organised. Many more musicians and singers were attacked, beaten, kidnapped and killed, while others were forced to either quit the music profession or leave the country. Music stores and CD shops were blown up with explosives. KP’s music scene was destroyed.

The artistes’ community breathed a sigh of relief when the Awami National Party (ANP) came into power, from 2008 to 2013. Peshawar’s Nishtar Hall, once again, resounded with music and cultural activities. Musicians, poets and writers regained their lost spirit. The lights came back on in the city’s cinema halls. The revival was slow, but provided some succour to the demoralised artistes. The Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf’s (PTI) provincial government took another positive step by launching a monthly stipend for 500 artistes, under which they receive Rs 30,000 each. But their ordeal is not over.

Tariq Hussain Bacha, press secretary of the Music Welfare Society (MWS) in Peshawar, told Newsline that the public’s perception of art and artistes in KP needs to be corrected and their status recognised. He said that artistes and performers were not rewarded for their efforts and came to a sorry end. “The provincial government believes that by holding a few ‘cultural festivals’ it is serving artistes and promoting art, yet they do not heed our cries for help,” he says.

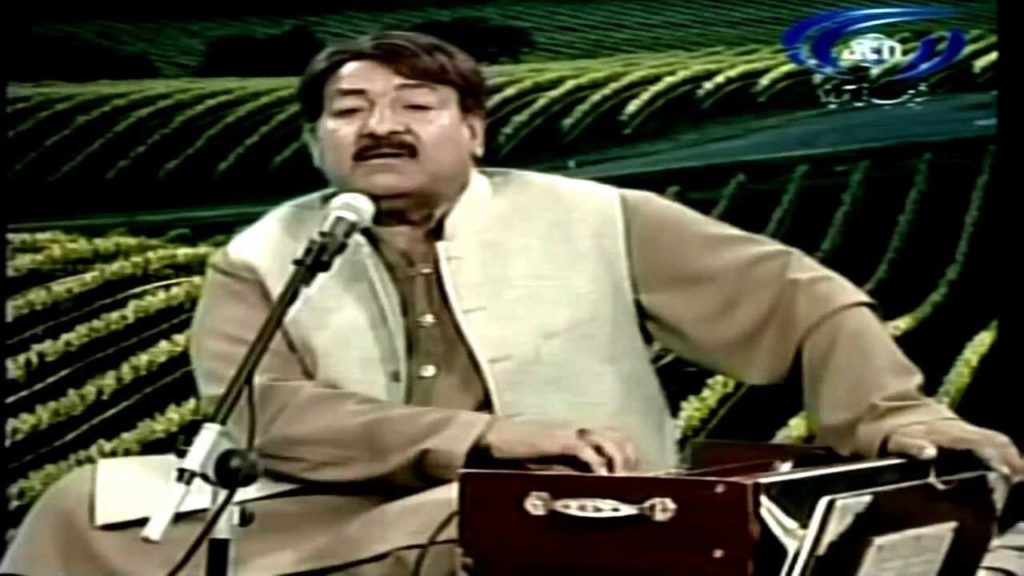

Gulzar Alam

Khial Mohammad

Even today, noted senior musicians and singers – Hidayatullah, ghazal maestro Khial Mohammad, Ustad Ahmad Gul, Wagma and Akbar Hussain – are just a few examples of artistes in need, while popular folk singers like Mashooq Sultana, Khan Tahsil, Qamru Jan, Gulab Sher, Ustad Iftikhar Qasir and Naeem Jan passed away without receiving any aid or recognition from the government.

Ihtisham Toru, senior journalist and chief of the Cultural Journalists Forum (CJF), while sharing his views on the plight of Pashto music, said there was still a pall of darkness over the Pashto music scene and their financial woes were multiplying. He said the recent migration of senior Pashto folk singer, Gulzar Alam, to Kabul due to his insecurity and poor financial condition was a blow for the community.

“Successive provincial governments in the KP, including the incumbent PTI, have not managed to draft a comprehensive cultural policy,” laments Toru. “Although the PTI’s monthly stipend for deserving artistes and the publication of books by poets and writers did have an impact on the literary and cultural scene, the situation is still far from satisfactory. I believe a well-defined cultural policy would resolve important issues being faced by the artistes’ community,” he continues.

Music director-cum-singer, Master Ali Haider, complains that each government runs different schemes in the name of promoting art, but nobody cares to address the genuine concerns. He said that KP now had no market for music and only a handful of young singers and actors ran their own web channels. He said traditional musicians, who were not familiar with modern digital gadgets, were no longer relevant to the audience. “Musicians and singers have no voice in policy-making,” says Haider.

According to Akbar Hoti, an official of KP’s directorate of culture, the finalisation of KP’s cultural policy is just around the corner and will resolve most issues faced by the artistes. He said that the directorate of culture had compensated ailing artistes with an ‘illness allowance,’ while the process of setting up an art academy — Hunargah — was also in its final phase.

On the question of Gulzar Alam’s shifting to Afghanistan, Hoti said that Alam had not approached the directorate of culture for financial support and that the folk singer had, nevertheless, been compensated on several occasions. “The third phase of our popular scheme involves a hefty monthly stipend for artistes, performers and folk singers. Young artistes, instrumentalists, singers and performers will be trained at the art academy,” assured Hoti.

While the PTI government has, at the very least, good intentions, there is a prevalent fear that this may be another case of too little, too late.