The Rise of the TLY

By Ali Arqam | Cover Story | Published 8 years ago

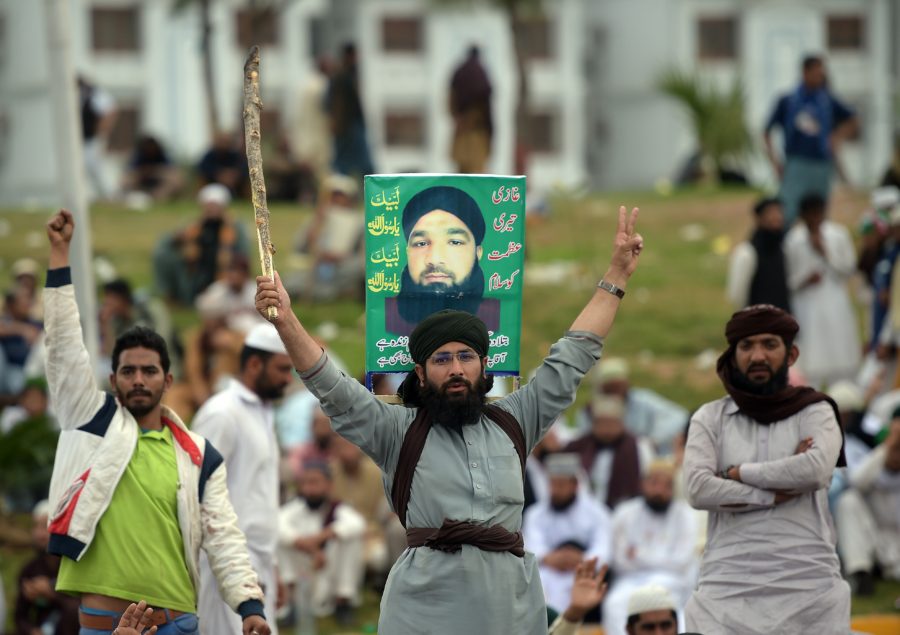

Supporters of executed Islamist Mumtaz Qadri shout slogans during an anti-government protest .

Over the last two decades, Pakistan has been in the grip of militant violence perpetrated by the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ). Both groups belong to the Deobandi sect, and have partnered with Salafists like Al-Qaeda and its affiliates in mounting terror attacks inside Pakistan. Their opponents from the Barelvi school are inclined towards Sufism. Most of their activities revolve around Sufi shrines, and their leadership comes from the Pirs and adherents of Sufism spread across Pakistan, mostly in Punjab and Sindh. The Barelvi school has thus stood in opposition to the violent tactics and terror narrative of the Deobandis and their sympathisers in various religious groups.

However, the Mumtaz Qadri affair — when then Punjab governor Salmaan Taseer was assassinated by his bigoted bodyguard — brought the radical side of the Barelvi school forward. At the time, many small political and religious groups capitalised on the idea of protecting the honour of the holy Prophet (Pbuh) and portrayed Mumtaz Qadri as their poster boy. Eid-e-Milad-un-Nabi processions were held with participants holding posters of Mumtaz Qadri, and reciting Naats — poems in praise of the Holy Prophet (PBUH). Slogans were raised threatening to slit the throats of blasphemers: “Gustakh-e-rasool ki ek saza, sar tan se juda juda, (Only one punishment for the blasphemers, sever their heads from the bodies).”

During the last quarter of 2010, the ruling Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) was faced with challenges on multiple fronts. The country was hit by massive floods, affecting 18 million people across Pakistan, while around 2000 people were killed. Starting from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the floods spread south through Punjab, Balochistan, and Sindh, causing internal displacement, and requiring widespread rehabilitation work. Crippled on the economic front, the government relied on financial aid from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) which specified, among its conditionalities, certain tax reforms. The government’s subsequent bid to introduce value added tax (VAT) was appreciated by economists, but resisted at different levels, by the opposition parties, traders and businessmen.

On another front, progressive elements within the PPP were asking for amendments in the blasphemy laws, as blasphemy allegations were often used against members of religious minorities to settle personal scores. In one such case, in August 2009, a Christian neighbourhood in Gojra, in the Punjab, was attacked over the alleged desecration of the Quran, resulting in deaths and mayhem.

At the time, Salmaan Taseer, the slain governor of Punjab, stood up in support of Asia Bibi, a working class Christian woman charged with blasphemy. Taseer tried to get her a presidential pardon, which led to an intense debate and brought Taseer under fire; the controversy was fuelled by some TV channels, who gave voice to clerics issuing religious decrees against Taseer.

Taseer was critical of the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N)-led provincial government in Punjab. His jabs at the PML-N for its close ties to banned sectarian organisations and seeking electoral support from their leadership in by-elections, irked the PML-N ministers, especially law minister Rana Sanaullah.

The ruling PPP tried desperately to defuse the tensions, as it needed support from the traders’ bodies for the VAT, later renamed the revised general sales tax (RGST). The PPP information secretary, the late Fauzia Wahab, spoke about resistance from traders over tax reforms, and how conservative elements within these circles were exploiting the ongoing debate around blasphemy laws to divert attention from economic issues, while some political parties were also taking advantage of the situation.

On the fateful day of January 4, 2011, Salmaan Taseer was assassinated by his own bodyguard from the Punjab Police elite force, Mumtaz Qadri, who pumped 28 bullets into his body with his rifle. The assassination led to a verbal spat between the PPP, the ruling party at the centre, and the PML-N, as Fauzia Wahab termed the act a political assassination. The debate soon took a new turn, as Mumtaz Qadri, who belonged to the Barelvi sect, was projected as a heroic figure for killing the governor of Punjab, who had dared to criticise the abuse of the blasphemy law.

The delay in Qadri’s conviction, reports of his luxurious life behind bars, and his defence by a powerful panel of lawyers, that included former judges of the high court, gave the impression that he would not be convicted and literally get away with murder. The kidnapping of Salmaan Taseer’s son, Shahbaz Taseer, added to the delay in bringing Qadri to justice, as the militants who had kidnapped Shahbaz threatened to kill him if Qadri was prosecuted.

Qadri was hanged on February 29, 2016, after the higher judiciary upheld his conviction, and a mercy petition was rejected by President Mamnoon Hussain. His funeral procession drew huge crowds, and gave birth to a new religious front, the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Ya Rasoolullah (TLY), constituted by pirs and custodians of Sufi shrines. It had allies from the Barelvi sect, the Pakistan Sunni Tehreek (PST) being the most prominent.

Getting a lifeline from Qadri’s death, and the response to his funeral procession, the PST, an influential group in Karachi and parts of Punjab, known for its strong-arm tactics, violent tendencies, and MQM-style organisational structure, announced Qadri’s chehlum (the ritual of commemorating the 40th day of death) along with the TLY. The groups gathered at Liaquat Bagh Rawalpindi, but didn’t stop there and marched towards Islamabad’s D-Chowk for a sit-in to get a set of 10 demands approved by the government. The demands included unconditional release of all Sunni clerics and leaders booked on various charges, including terrorism and murder; declaring Mumtaz Qadri a martyr and conversion of his prison cell at Adiala Jail into a national heritage site; assuring that the blasphemy laws would not be amended; and the removal of Ahmadis and other non-Muslims who occupied key posts. They also demanded execution of all the blasphemy accused, including Asia Bibi.

The protest turned violent as the protesters clashed with security forces, damaged buildings, set fire to a Metro station, containers and buses, and beat up policemen. City Police Officer, Israr Ahmed Abbasi, was among the dozens who were injured in the clashes. The dharna also led to the closure of roads and suspension of cellular services in the Red Zone. Former Interior Minister, Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan, issued a warning to the protesters, and criticised the Punjab government for not taking necessary measures to prevent the protesters from entering the red zone. Then Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif addressed the nation on the night of March 28, warning radical Islamists that the leniency of the government and law enforcement agencies should not be mistaken as a sign of weakness. Later, the sit-in ended after negotiations with the government.

The TLY also surfaced at a time when social media activists were picked up and civil society organisations were demanding their recovery. These activists were accused of blasphemy by dubious social media accounts. The TLY confronted civil society organisations for their support to the missing activists, with its zealots pelting stones at one such protest in Karachi.

The recent performance of the TLY in the by-elections in Lahore and Peshawar has surprised many. If the PML-N does not manage to strike a deal with the TLY before the upcoming elections, the rise of the TLY may cut into their vote bank in different constituencies. It may also cause a switch of electables, who are linked to different Sufi clans, or adherents of the pirs and custodians of these shrines.

In Karachi, the PST could pose a threat to the rival MQM factions and cause a further split in the Mohajir vote, especially in Baldia Town, Orangi Town, Garden East and West and old city areas, as it has shown its strength in the recent sit-ins in multiple locations across Karachi.

Ali Arqam main domain is Karachi: Its politics, security and law and order