The Day After

By Rahimullah Yusufzai | News & Politics | Published 14 years ago

After being on the run for years, Osama bin Laden’s luck finally ran out on May 2 when US Special Forces secretly flown in on four military helicopters from Afghanistan got him in a large house in the Pakistani garrison town of Abbottabad. Two bullets to the head and chest did the job, and his body was taken away first to the Bagram airbase north of Kabul and later ‘buried’ in the Arabian Sea.

Notwithstanding denials of his death by some of his loyalists, the chapter of bin Laden’s eventful life has been closed and a new one opened posing disturbing questions about his presence in a compound located uncomfortably close to the Pakistan Military Academy, Kakul, where army officers are commissioned in a town sited only 71 kilometres from the federal capital, Islamabad. It has caused huge embarrassment to the Pakistan government and its security forces and law-enforcement agencies. Though officials of the powerful Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) have conceded their failure to capture bin Laden and reminded the world not to forget the umpteen times that it succeeded in netting other terrorism suspects, probing questions are being asked regarding whether Pakistan’s security apparatus was complicit or merely incompetent in letting such a high-value target live undetected in a relatively small town like Abbottabad. The incident will also shape the future of the uneasy and distrustful relationship between Pakistan and the US and set the course of the seemingly unending war against terrorism (read “Strained Bedfellows“).

Another worrying aspect of the incident was the inability of Pakistan’s large and apparently overrated military to detect the American helicopters that entered the country’s airspace, flew all the way to Abbottabad, accomplished the 40-minute raid at the bin Laden compound and returned without being challenged. Pakistanis were quick to ask whether their nuclear assets could also be taken out with equally apparent ease. The Indians, forever ready to exploit Pakistan’s weakness, rubbed salt on its wounds when the Indian Army chief General VK Singh claimed that India’s armed forces were competent to carry out an operation in Pakistan against Pakistan-backed militants operating in Indian-administered Kashmir or those linked to the Mumbai blasts in 1993 and later in 2008, similar to the one conducted by the US against bin Laden. And Afghanistan’s defence ministry, whose premises in Kabul were attacked by the Taliban a few weeks ago, wondered whether Pakistan was capable of protecting its nuclear sites. Insulting remarks were also made elsewhere in the world, particularly in western capitals, and the CIA director Panetta, designated as the next defence secretary in place of Gates, made it clear that Pakistan wasn’t informed about the Abbottabad raid due to concerns that the information would be leaked.

Despite Pakistani denials, bin Laden seems to have found refuge in the country sometime after the fall of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. Although he did not cross over to Pakistan’s tribal areas immediately after the Tora Bora military campaign by US forces in December 2001, it is possible that he came later and lived in not one, but several places. South Waziristan, North Waziristan and Bajaur were always mentioned as his likely hideouts, not because he was sighted there but due to the fact that these were strongholds of the Pakistani Taliban aligned to him. The fact that a number of important Al Qaeda operatives, including Khalid Sheikh Mohammad, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, Abu Zubaydah, Abu Faraj al Libbi, etc were captured in Pakistani cities would most likely have alerted the intelligence agencies about bin Laden’s presence in some urban centre and not in the remote tribal areas. But none could have conceived that he would be living with his family in the peaceful summer hill-station, hitherto not linked to any terrorist activity. This could be precisely the reason that bin Laden chose Abbottabad as a hideout, because he believed the sleepy little hamlet would not arouse any suspicion.

Despite Pakistani denials, bin Laden seems to have found refuge in the country sometime after the fall of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. Although he did not cross over to Pakistan’s tribal areas immediately after the Tora Bora military campaign by US forces in December 2001, it is possible that he came later and lived in not one, but several places. South Waziristan, North Waziristan and Bajaur were always mentioned as his likely hideouts, not because he was sighted there but due to the fact that these were strongholds of the Pakistani Taliban aligned to him. The fact that a number of important Al Qaeda operatives, including Khalid Sheikh Mohammad, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, Abu Zubaydah, Abu Faraj al Libbi, etc were captured in Pakistani cities would most likely have alerted the intelligence agencies about bin Laden’s presence in some urban centre and not in the remote tribal areas. But none could have conceived that he would be living with his family in the peaceful summer hill-station, hitherto not linked to any terrorist activity. This could be precisely the reason that bin Laden chose Abbottabad as a hideout, because he believed the sleepy little hamlet would not arouse any suspicion.

Bin Laden was a wanted man, not since the 9/11 attacks against the United States of America as everyone is stating, but from 1996 onwards when he returned to Afghanistan in a chartered aircraft from Sudan and was already very critical of American policies in the Middle East. He had survived an attempt on his life in Sudan, where he had shifted from his homeland Saudi Arabia after developing differences with the Saudi royal family over its decision to seek US military assistance in the Gulf War. The obvious place for him to find refuge then was Afghanistan, his ‘second home’ where he had fought in the 1980s as a young man, along with the Afghan mujahideen resisting Soviet occupation. Once settled near Jalalabad in eastern Afghanistan, initially under the protection of the Afghan mujahideen government of Prof Burhanuddin Rabbani and his allies Maulvi Yunis Khalis, Haji Qadeer and Engineer Mahmood, and later the Taliban, he set up Al Qaeda, declared jihad against the US and Israel, and mobilised his supporters to attack American embassies and other installations.

The US tried to eliminate him in August 1998, when President Bill Clinton ordered the firing of around 80 Tomahawk cruise missiles at his training camp in Afghanistan’s Khost province to avenge the attacks on the American embassies in Kenya and Tanzania.

The hunt for bin Laden intensified after the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Centre, New York and the Pentagon in Washington. However, the world’s biggest manhunt never made any real headway and US officials including defence secretaries Donald Rumsfeld and Robert Gates and the CIA chiefs Leon Panetta, Michael Hayden and others before them often admitted to having lost track of him. Just when bin Laden’s trail got cold, amid speculation that he may be dead from supposed ailments such as an old kidney disease or killed in a military operation, the US got lucky by identifying his trusted courier during interrogation of captured Al Qaeda operatives including Khalid Sheikh Mohammad and Abu Faraj al-Libbi. Sections of the US media are already reporting that unlawful interrogation techniques including water-boarding were used to obtain some of the precious clues that led the CIA to the courier, Sheikh Abu Ahmad, who reportedly was killed along with bin Laden in Abbottabad.

A debate has also started in the US and the European media about the legality of shooting the unarmed bin Laden dead in the all-to-familiar CIA and American fashion instead of capturing him alive. While US Attorney General Eric Holder emphatically declared that “the operation in which Osama was killed was lawful,” former West German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt said the manner in which Osama was taken down “was clearly a violation of international law.” London-based human rights lawyer Geoffery Robertson stated the killing “may well have been a cold-blooded assassination.”

Islamic groups have termed Osama’s killing an ‘execution’ and it is being argued that this could enable the followers of the Al Qaeda founder to glorify him as a martyr who fulfilled his word never to surrender to his enemies. Add to it the manner of his burial in the sea “in line with Islamic rituals” as the US government is claiming, and we have an ideal situation for the Islamists and militants to use as a rallying point and recruitment tool to continue the fight against an arrogant America. Islamic scholars have termed the ‘burial’ at sea un-Islamic and inflammatory, as this is allowed only if a person dies while at sea far from land. Besides, they argue the first right on a body is of the family. While the Bin Ladens, one of the richest families in Saudi Arabia and the owners of a giant construction firm, reportedly refused to take the body when offered by the US, the same offer was apparently not extended to his wives or children.

The decision by the Obama administration not to show pictures of bin Laden’s body because they were gruesome, will inevitably add fuel to fire and lend credence to the growing belief that he may have been tortured to death or disfigured afterwards.

The decision by the Obama administration not to show pictures of bin Laden’s body because they were gruesome, will inevitably add fuel to fire and lend credence to the growing belief that he may have been tortured to death or disfigured afterwards.

Another reason for killing bin Laden instead of taking him into custody is stated to be the American concern about a long and messy court trial that could have provided him an ideal opportunity to reveal uncomfortable secrets about things past, including the Afghan jihad. Getting bin Laden convicted would also have posed problems as hard evidence against him might not be available because he often tended to deny his own and Al Qaeda’s involvement in acts of terrorism. In two interviews with this writer in Afghanistan’s Khost and Kandahar provinces during the Taliban rule in May and December 1998, bin Laden denied involvement in the bombings of the US embassies in Nairobi and Dar-es-Salam and the attack on the US battleship Cole off the coast of Yemen, but at the same time he praised the attackers as “martyrs.” His line of argument at the time was that by declaring jihad against the Jews and “Crusaders” he was trying to make the Muslims aware that their real enemies were Israel and the US, and mobilising them to fight against the two to avenge their losses and humiliation.

However, long before the Al Qaeda leader was killed, certain US officials and sections of the media had discussed what to do with him in case he was discovered. It has been suggested that the American people were being primed for his death. Attorney General Holder even told a House of Representatives panel some time back that bin Laden “will never appear in an American courtroom.”

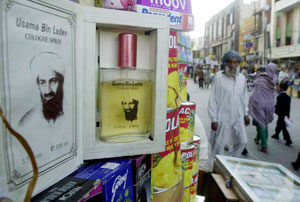

The Saudi-born bin Laden harboured a death wish and that has been fulfilled. He generated controversy both in life and in death. Many people used to comfortable living cannot fathom the fact that a millionaire like him gave up the luxuries of life to live and fight in the mountains of Afghanistan due to his commitment to jihad. He was ‘disowned’ by his own family and stripped of his Saudi Arabian nationality. His actions, in particular the Al Qaeda-sponsored 9/11 attacks against the US, divided Muslims and led to the American invasion of Afghanistan and the fall of the Taliban regime. Osama bin Laden had a point when he criticised unconditional US military and economic assistance to Israel to occupy Palestinian territories and objected to the presence of western forces in his homeland, Saudi Arabia, on patriotic and Islamic grounds. But the violent tactics that he and his men employed to achieve these objectives and Al Qaeda’s terrorist attacks that killed innocent people spoiled his cause. His actions became indefensible and the number of his supporters dwindled. Bin Laden gradually became a political nonentity.

Post-bin Laden, it is possible that Al Qaeda will survive as a weakened armed group under his likely Egyptian successor Dr Ayman al-Zawahiri, but its appeal has faded. The recent uprisings in Arab countries have made Al Qaeda’s violent philosophy irrelevant as it has dawned on the Ummah that change is possible through peaceful rather than military means.

Related articles from the May 2011 cover story:

Related articles from our Blog Row:

“The Guy who Liveblogged the Osama Raid Without Knowing It”

Musharraf Cries Wolf over Violation of Sovereignty

Video: Husain Haqqani on CNN after the OBL raid

Unsurprising Secret Deal has Become a Raw Deal

Rumsfeld Talks Frankly About Imperfect Relationship with Pakistan

This article was originally published as part of the cover story in the print edition of Newsline for May 2011.

Rahimullah Yusufzai is a Peshawar-based senior journalist who covers events in the NWFP, FATA, Balochistan and Afghanistan. His work appears in the Pakistani and international media. He has also contributed chapters to books on the region.