The Others and Otherness

By Suleman Akhtar | Newsbeat National | Published 6 years ago

The term Ahmadi applies neither to a person nor a belief. In the context of Pakistan, Ahmadi is a condition of otherness. It is the cornerstone against which the sameness is measured — the sameness of being a true Pakistani. Ahmadi is the make-do answer of the legitimate question that remains unresolved to date — the question of national identity. The problem faced by Pakistan is not the answer, but the question itself.

The PML-N leader, Captain (retd) Safdar, took the floor of the National Assembly in October only to go into a venomous tirade against the much persecuted Ahmadi community of Pakistan. He called for a blanket ban on their induction in the army, called into question their loyalty to the country, and criticised the re-naming of Quaid-e-Azam university’s physics centre after Dr Abdus Salam — the first Pakistani Nobel laureate, and an Ahmadi by faith.

The retired Captain – who happens to be former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s son-in-law – ranting against the most vulnerable community of Pakistan, hoping to gain some political mileage, was not a novel spectacle. It was Mumtaz Daultana, the second Chief Minister of Punjab from 1951 to 1953, who first exploited the anti-Ahmadi sentiments fanned by Majlis-e-Ahrar-ul-Islam during that time. He hoped to earn political mileage from the situation by discrediting the central government — headed by a Bengali Prime Minister, Khwaja Nazimuddin — against the background of the then ongoing discussions of the Basic Principles Committee which was to determine the underlying principles of the future legislature. The situation culminated in the 1953 Lahore riots, resulting in hundreds of deaths and imposition of Martial Law in the city.

The retired Captain is not the first one to distort history by eulogising Attaullah Shah Bukhari and Jinnah in the same breath. Syed Attaullah Shah Bukhari — one of the founding members of Majlis-e-Ahrar — was a fierce critic of Jinnah and the Muslim League. His party called Pakistan ‘Kafiristan’ and another founding member of the Ahrar, Mazhar Ali Azhar, wrote a famous couplet: “Ik kafira kay peechay Islam ko chora / Yeh Quaid-e-Azam hai ke kafir-e-azam.”

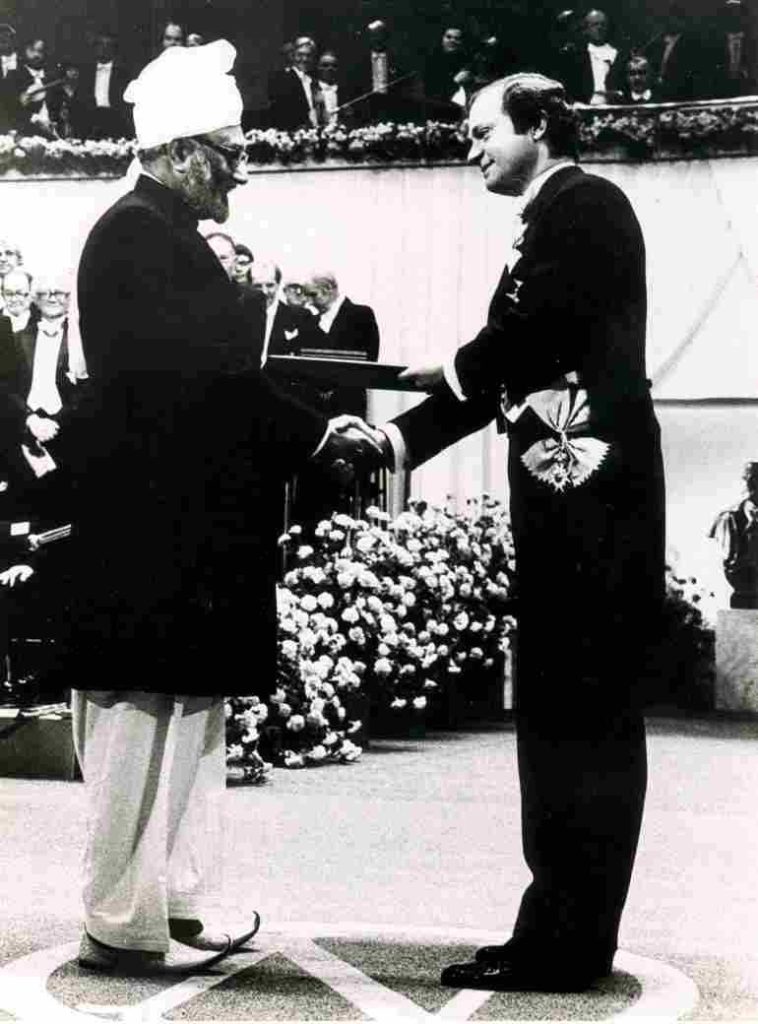

Prof Abdus Salam receding the Nobel Prize from the King of Sweden.

Another target of the retired Captain’s speech, Zafarullah Khan — the first Foreign Minister of Pakistan — was appointed by Jinnah himself to represent the Muslim League before the Radcliffe Boundary Commission. The revisionism and obscurantism of history in Pakistan is so complete that the figure of Jinnah resonates brilliantly with the ones who would otherwise have been its antithesis.

Safdar’s speech was, by any definition, a hate speech delivered at a time when the ruling party could really use some political gains. However, at the heart of it lie the very fundamental questions of citizenship, the role of religion in shaping national identity, and the role of the nation-state in the context of Pakistan. That a hate speech was delivered on the floor of the Parliament and not a single member of the assembly dared to protest, is probably the most disturbing aspect of all. The parliament, however, has been a party to it for long.

The separation of East Pakistan in 1971 was not merely a territorial loss; it also inflicted immense harm on the ideological body of Pakistan. Pakistan was Muslim before 1971. It did not survive in that form. It had to be something else in order to survive. It became ‘good’ Muslim after 1971. This is where 1974 comes into the picture, when the state expropriated the clerics’ role. Apart from the myriad other factors, including the strong first-time presence of ulema in parliament and a populist party at the helm, the Second Amendment was enacted in the backdrop of a polity struggling to answer the question of a marred national identity.

Poets and poets alone have the ability to give simple voice to complex philosophies and prophecies. It was a poet and politician, Afzal Randhawa, who observed in the assembly during the open discussion in the House before passing the amendment in 1974: “[If Ahmadis] could not be good Muslims, how could they be good Pakistanis?” This simple observation embodies the underlying criterion upon which nationhood was to be based — a state-sanctioned subject of inseparable overlapping national and religious identities. The problem, however, is that when good is imposed by the authority, the bad needs to be defined too. There can exist no authoritarian sameness without conjuring up otherness. The Ahmadi, as we know it today, is our other. We have invented it; secularly and constitutionally.

Once the otherness is invoked, it has this eerie ability to crawl into the hitherto undiscovered boundaries of the sameness — the peripheries. The deadly violence against the Pakistani Shia community in recent years is a case in point. A classic example here is the plight of the Shia Hazara community, that is not only the other by sect but also by appearance — the recognisable other.

During the heydays of the lawyer’s movement, Aitzaz Ahsan popularised a slogan by equating the state with the mother figure: “Riasat ho gi maan ke jaisi” [The state will be like the mother]. He quoted some verses of one of Afzal Randhawa’s Punjabi poems in his book, The Indus Saga. The poem is an appeal to the mother. Today, it captures the plight of the distressed minorities of Pakistan appealing to the state.

Oanay phat meray jusay tay

Jinnay tere waal ni maaye

Hun te kujh nain nazrin aunda

Hor ik sooraj baal ni maaye

I have as many gashes in my body

As the number of hair on your head, oh mother

There is darkness all around me

Light up another sun, oh mother.