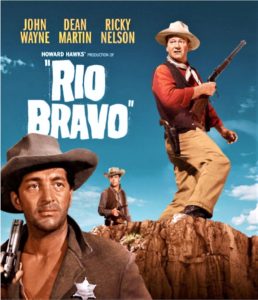

Classic Movie Review: Rio Bravo

By Ali Bhutto | Movies | Published 6 years ago

In his memoir, Hawks on Hawks, American director and producer Howard Hawks proposed that the one thing a filmmaker must prioritise above all else is the development of his characters. The plot, he argued, was secondary and of far lesser importance. “You just have the characters moving around. Let them tell the story for you,” he advised. In his 1959 western Rio Bravo, Hawks does exactly that. The film prioritises a quaint and cosy atmosphere over a storyline.

In his memoir, Hawks on Hawks, American director and producer Howard Hawks proposed that the one thing a filmmaker must prioritise above all else is the development of his characters. The plot, he argued, was secondary and of far lesser importance. “You just have the characters moving around. Let them tell the story for you,” he advised. In his 1959 western Rio Bravo, Hawks does exactly that. The film prioritises a quaint and cosy atmosphere over a storyline.

Quentin Tarantino has described Rio Bravo as his favourite “hangout movie.” Throughout the film’s 140-minute duration, the audience is made to feel like they are hanging out with, and getting to know the main characters. These include Chance, the sheriff (John Wayne), Dude, his washed out deputy (Dean Martin), Feathers, Chance’s potential romantic interest (Angie Dickinson), Colorado, a young gun (Ricky Nelson), and Stumpy, the watchman (Walter Brennan).

The physical dimensions of the tiny fictional town of Rio Bravo compliment the lighthearted and playful dialogue that dominates the film. Hawks gets up close and personal with the standard one-street town of the American west (shot in the desert surrounding Tucson, Arizona), where everything is a short stroll away. We follow the characters as they move from the saloons to the sheriff’s office and hotel, and feel increasingly at home amidst the worn-out brick walls.

Despite its laid-back vibe and deliberate meandering, it would be a mistake to think that the film lacks direction, or purpose. For in this quiet, unassuming desert town, there is a ticking time-bomb waiting to go off.

The spectre of outlaw Nathan Burdette (John Russell) haunts the sheriff and his friends. Burdette is plotting to free his brother, who has been locked up by the sheriff for murder. Chance and his unlikely coterie are clearly the underdogs when faced with Burdette, a wealthy rancher who is easily able to buy support and has a gang of gunslingers at his command.

As the tension piles up in a slow-burning fuse, the characters’ ability to remain jovial and in high spirits only adds to the suspense — the only thing that seems to get Chance worked up is the feisty Feathers.

Hawks deploys what Ernest Hemingway referred to as “oblique dialogue.” He describes this in his memoir as dialogue that is “three-cushion,” in which the characters do not make clear, straightforward statements, but instead say things in a roundabout way — for added effect.

Viewers will notice elements that clearly influenced and inspired Tarantino. The scene in which a band of Mariachis play ‘El Deguello’ — which Colorado describes as “the Cutthroat Song” — will remind audiences of Tarantino’s tactful use of similar music in his films to create atmosphere and a build-up to an explosive finale.

The writer is a staffer at Newsline Magazine. His website is at: www.alibhutto.com