The New East India Company?

By Aasim Zafar Khan | Cover Story | Published 8 years ago

Invasions are expensive. Take the American invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, for example. Combined, the two misadventures have cost the United States a total of $2.4 trillion to date. And in both campaigns, the US has eventually withdrawn, without having achieved any of their desired aims. Iraq didn’t have any weapons of mass destruction (WMD). But today, thanks to the invasion and the ensuing jihad, they now have the Islamic State.

Afghanistan is not any better. The Taliban movement is stronger than ever, there is no democracy outside Kabul, and numerous terror groups such as Al Qaeda, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, and the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, to name a few, continue to operate in the country’s eastern and northern regions.

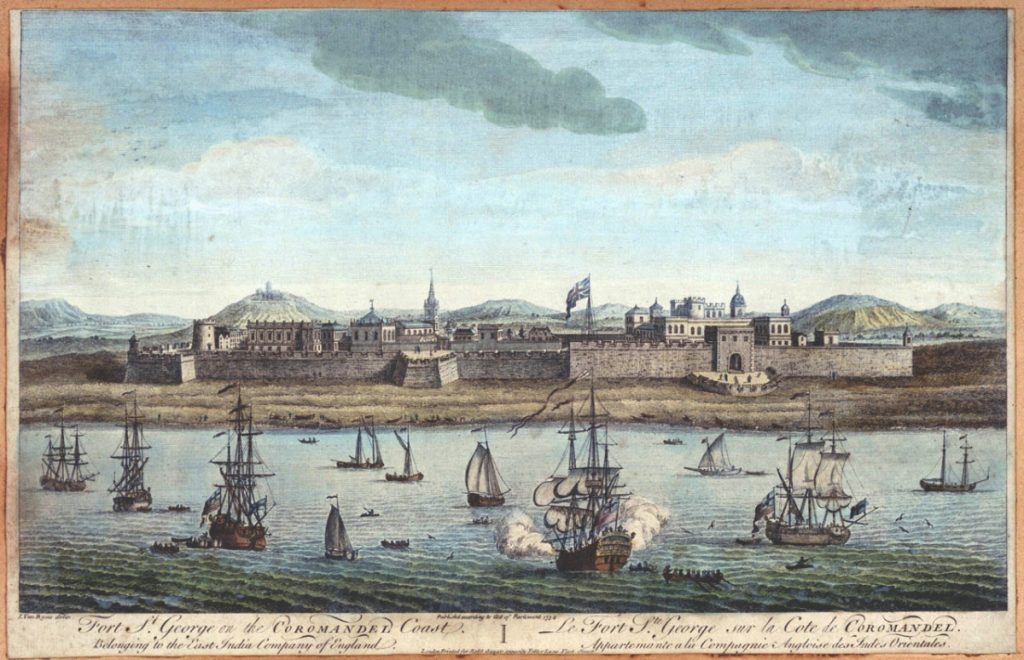

Fort St George on the Coromandel Coast. Belonging to the East India Company of England

The most powerful type of invasion is economic. Most wars are usually fought for this reason. Iraq was never about WMDs and Saddam Hussein. It was about oil. And while there are key economic reasons for the invasion of a particular country, what if you take the invasion out of the equation and leave the economics behind? Take the East India Trading Company (EITC). Formed for the exploitation of trade in East and Southeast Asia in 1600, it gradually became involved in politics, and later started acting as an agent of British imperialism in United India from the early 18th century to the mid-19th. However, due to the presence of other European trading companies, the EITC required military power as well. Little by little, the EITC established its military supremacy over the other Europeans in the area, and this culminated in the seizure of Bengal in 1757.

A general view of Pakistan’s Gwadar deep-sea port

Eight years later, the Mughal Emperor at the time granted the EITC the right to harvest the revenues of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. And the precedent was set.

In Pakistan today, the Chinese are everywhere. In marketplaces and movie theatres, in schools and at hospitals. Not that this is something new, because the Chinese have always been around. But by and large, in the past they were mostly involved in running restaurants and/or salons. But not anymore. In the decade leading up to the announcement of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the Chinese presence in Pakistan began to expand. Companies like Huawei and Zong, to name a couple, dropped anchor and have now become household names. Today, around 700 small and large Chinese companies are working across the country. Recently, 40 per cent strategic shares of the Pakistan Stock Exchange were sold to a Chinese consortium as well. And who can forget the handover of Gwadar port?

The golden rule is that no state-owned enterprise can be acquired by anyone unless it goes through a process of privatisation. So the Karachi Electric Supply Company (KESC), was sold through privatisation to Abraaj, who have now sold their shares to Shanghai Electric.

The CPEC is a different beast altogether. Worth nearly $50 billion, it is overflowing with projects that will, it is believed, correct Pakistan’s course once and for all. The question is, at what cost? It was recently reported that on CPEC investments of $50 billion, Pakistan will have to repay $90 billion — ie. about $3 billion a year in the 30-year repayment period. Add to this the fact that nobody is certain about the terms of the deals struck with the Chinese, nor how this debt will be repaid. One thing is for certain though: the CPEC is not a gracious gift from our all-weather friend. Will all the investment lead back into yet another debt trap? What if Pakistan is unable to add this debt burden on to the one it already carries on its back? What will we be able to give as collateral?

There have also been recent reports that the Special Economic Zones being made under the CPEC will only be open to Chinese investors. This was later refuted by the powers-that-be, but as is often the case in Pakistan, we won’t really know till we know.

At the same time, Chinese influence in Pakistan’s foreign policy continues to grow. It is an open secret that Beijing has been pushing Islamabad to bring the Afghan Taliban to the table. It has also pushed Pakistan to begin a process of rebuilding ties with Russia — one of China’s closest allies.

The CPEC is not a free meal, and Chinese interests in Pakistan are a means to an end for them. This needs to be understood, and the state needs to open up on the terms of engagement between Islamabad and Beijing. Otherwise, a few years down the line, we might find ourselves selling Pakistan by the pound.

The writer is a journalist based in Lahore. He is the current managing editor of MIT Technology Review Pakistan, a bi-monthly science and technology magazine.