New Belt, Old Route

By Raheel Shakeel | Cover Story | Published 8 years ago

Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China, unified several warring kingdoms in 221 BC into one polity. The unification and his administrative reforms would set the template for all the subsequent dynasties of China, over two millennia of dynastic rule. It is thanks to him that the Chinese state has been the longest enduring polity in the history of nations. The Han Dynasty which followed Qin Shi Huang’s Qin Dynasty, led to another Golden Age of China, in wealth and power. The Hans were the ones who formalised the Silk Routes — a constellation of trading routes on the Eurasian landmass. In that sense, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) or One Belt, One Road (OBOR) aren’t truly novel conceptions, but rather a modern reiteration of the ancient world’s trading network.

And yet, the Silk Road was the exception rather than the rule when it came to China’s engagement with the world. The seclusion in which Chinese monarchs held court, where, even their supplicants had to pay homage a few hundred paces away from their regent, is a perfect parable of China’s engagement — or lack thereof — with the wider world throughout its history. Despite having human, military and technological resources, the Chinese never ventured out of their own self-imposed confines; there never was to be a Chinese Alexander, Genghis Khan or Julius Caesar. It never held any imperial ambitions for world domination. Historians still scratch their heads about the time when, during the Ming Dynasty in the 14th century, the famous Chinese Muslim explorer Zheng He, led naval expeditions as far away as Africa, not for profit or gain, but rather as an exercise in vanity. Adding to that, after the expeditions, the Ming burned their naval fleet to resume China’s splendid isolation. Contrast that with the European Voyages of Discovery (or rather savagery) which were singularly focused on land, gold and glory, by hook or by crook.

Modern China’s violent birth was midwifed by a civil war between the Nationalist forces of Chiang Kai-shek (the Kuomintang) and Mao Zedong’s Peoples Liberation Army. Mao’s Communist cadres would emerge victorious and set up the People’s Republic of China after the Second World War, China’s radical break with history ending dynastic rule. The Koumintang fled to Taiwan, the island’s fugitive status a painful relic of its past.

A similar break with history happened when Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms awakened the Chinese dragon. The global economy has never been the same since. The three preceding decades must surely rate among the most magnificent transformations any country has undergone. Brand China is the factory of the world and a pillar on which the global economy rests. The genius of Deng Xiaoping’s reforms was that while the political system remained Communist, the economic system was transformed into a dynamic capitalist one, unleashing the vast entrepreneurial energies of the Chinese. This marriage of convenience has propelled China to the commanding heights of power it finds itself in today. The Chinese dragon’s oscillation between isolation and engagement, and its subsequent spectacular opening up to the world would serve as the preamble to today’s CPEC. It is through this wider historical lens that one can have a better understanding of the modern, confident China of today, staking its claim in the global world order.

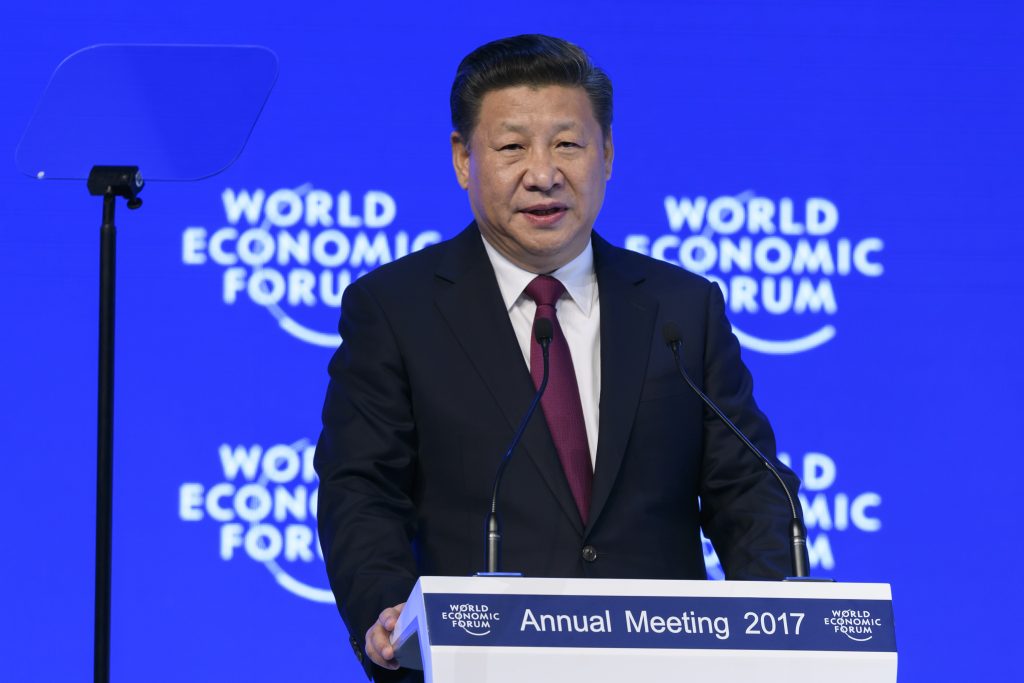

“China will keep its door wide open (to the world),” exhorted unlikely internationalist, Xi Jinping, at The World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2017, to raucous applause by a nervous global elite in the high noon of hyper-nationalism. As the first Chinese president to attend the global forum, his presence and commitment to internationalistic values served a symbolic purpose: a reassurance that China would pick up the baton which the United States and the Europeans had dropped. Globalisation would find its unlikely patron in China in an era when America, the global policeman, and a divided European Union, are recoiling inward, buckling under populist pressure at home rather than steward the liberal international order as they always have.

This changing of the guard can be no more apparent than in the sudden demise of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). In the Obama years the Chinese looked on in nervous trepidation as the US led the initiative in the largest free trade deal in recent decades. The TPP was to include 12 Pacific Rim countries including Japan, Canada and America, with the conspicuous absence of China. It was to comprise two-fifths of the global economy, easily eclipsing the European Union and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). This was to be the gilded skein that would hem China in. Fortunately for China, the TPP was pronounced dead on arrival by Donald Trump on his first day at the White House, who labelled it a “horrible deal.” This was a godsend for the Chinese. Since then, they have raced aggressively to fill in the vacuum left by the US in pursuit of their global ambitions, of which the CPEC and OBOR are the linchpins.

China’s President Xi Jinping

In the grand symposium held in May of this year in China for the OBOR summit, 29 heads of state — including our own Prime Minister — with a motley bunch of minister-level delegations from countries coming from all corners of the globe, attended the forum. Dignitaries from the IMF, the World Bank and the UN Secretary-General were also present. A ringing endorsement of China’s global ambitions was on full display. Ironically, the values of free and fair trade espoused by the Anglo Saxon world, is now seing its great practitioner in an Asian Communist regime. A Bretton Woods of our times is in the making.

There is no endless economic growth, and China is no exception. Gone are the days of double-digit GDP growth of the ’90s. Economic growth has been restricted to between five and six per cent. That has sent alarm bells ringing in many Chinese policy circles.

Then there is the hairy issue of Chinese debt, mostly on the books of many Chinese state-owned corporations. As is stands, the debt to GDP ratio rose from 155 per cent in 2008 to 260 per cent by the end of 2015. A borrowing binge of this magnitude has almost always preceded an economic crisis. The gravity of a potential crisis can be further gauged by the fact that $30 trillion of assets are in the Chinese banking sector, making it the biggest of its kind in the world — with four of China’s biggest banks also the world’s biggest. The bond market at $7.5 trillion is the third largest in the world.

In the Chinese stock market collapse of 2015, the Chinese government injected $200 billion to shore up the equity markets. Meanwhile, $65 billion in bank loans have gone bad and $600 billion of capital outflows have been sent out of Chinese shores by the moneyed elite. The spike in non-performing-loans is another sign of the ailing health of the financial sector. The slowing economy and mounting debt in its state enterprises must have been one of the reasons, if not the reason, for China’s involvement in CPEC. The fiscal and monetary stimulus to Chinese corporations and banks from preferential terms may well help them stave off disaster in their home markets. Chinese labourers paid for by Chinese companies, using Chinese materials, financed by Chinese banks in development projects abroad, would mitigate the stresses of the circular debt in China’s domestic markets.

Small wonder then, that most, if not all, of the CPEC projects have not been up for competitive bidding as is the regular requirement for government tenders. Instead, the projects have been awarded to Chinese contractors with little or no scrutiny or due diligence by Pakistani authorities. In the worst case scenario, an economic glut brought on by the current precarious situation in the Chinese economy could dry out the funding required for CPEC projects.

Chinese President Xi Jinping and President Mahinda Rajapaksa launch the Colombo Port City Project.

However, the Chinese are exceptionally adept at financial prudence. Their investments of $3 trillion in US short term T Bills and Bonds kept the US dollar and interest rate yields afloat, averting a total meltdown of the global economy in the 2008 financial crisis. They played a major role in stabilising the global economy as it weathered its worst storm to date. So it would not be merely optimistic to imagine that the Chinese could very well recalibrate their economy and steer it to calmer waters in the years to come. But the risks for an implosion cannot be ignored.

The Sri Lanka basket case serves as a gloomy reminder for what could potentially go wrong for Pakistan in the CPEC. Sri Lanka is strategically situated. In recent years there has been a tug of war between India and China to woo this tiny nation in their bid for supremacy of the Indian Ocean.

China has pumped billions of dollars in developing two strategic ports: the Hambatota and the Colombo Port City Project (CPCP). This infusion of Chinese ‘aid’ culminated in Sri Lanka’s foreign debt skyrocketing from 36 per cent in 2010 to 94 per cent in 2015. Adding insult to injury, only two per cent of these Chinese loans are grants; the rest are commercial loans with six per cent interest. Loans from the Chinese EX-IM Bank (Export Import Bank) were given with the express purpose of buying Chinese products and services with Chinese labourers flown in for constructing these projects. A third of Sri Lanka’s revenues go towards servicing Chinese loans with total foreign debt service reaching $8 billion annually.

The risks of angering the Chinese came to the surface as the drama of the 2015 Sri Lanka elections unravelled, when the incumbent, Maithripala Srisena, displaced Mahinda Rajapaska by a narrow margin. Srisena’s campaign was singularly focused on an anti-China agenda with him proclaiming, “The land that the white man took over by means of military strength is now being obtained by foreigners by paying ransom to a handful of persons.”

However, political rhetoric rarely translates into political action — as the Sri Lankan premier would find to his dismay. The new administration tried to make an about-turn on its Chinese commitments to return to India’s axis. But aside from token assurances from its neighbour to the north, there was not much else on offer. Finding itself in a debt trap of its own making, the Sri Lankan government then made amends with its Chinese patrons, and actually doubled down on the scale and number of infrastructure projects financed by the Chinese.

The Sri Lankan fiasco should serve as instructive, as Chinese aid to Pakistan is identical in structure to the one doled out to Sri Lanka. The Chinese loans, much like every other loan, are not an act of altruism, but one of cold, calculated self-gain. There is little doubt that similar obstacles will be faced by successive administrations in Pakistan if they get too critical and breach the terms of the Chinese aid.

The Chinese and Pakistani diplomatic ties are nothing short of an enigma; two countries so different from each other in terms of language, culture, faith and religion have, nonetheless, developed a robust partnership that is the envy of the world. On the one hand is an economic power with an autocratic Communist regime, on the other hand is a fledgling economy aspiring to be an Asian tiger, trying to make good on its Islamic and democratic aspirations. This extraordinary relationship has led to the biggest gamble both these countries are making as they partner for the CPEC.

A famous Urdu proverb goes: ‘If you truly want to know someone, either work with them or travel with them.’ By that logic, the formal work relationship brings along with it attendant concerns of opposing self-interests, anxieties about subordination and cultural misunderstandings that could do irreparable damage to previously cordial relations. There would no doubt be similar stresses to test the resolve of these ‘Iron Brothers’ — as President Xi Jinping likes to say — as CPEC goes into its operational phase. With great opportunities come great responsibility. The burden will be on both the countries to make it an equitable and fair relationship that sets an example to the wider world.

The caveats illustrated are by no means destined to happen. It would be extremely cynical to write off China’s role in the CPEC as only of an extractive nature; it would be equally foolhardy for Pakistan to proceed with blind optimism.

After all, even if history may not repeat itself, it does rhyme. The British East India Company came to India on the innocuous pretext of trade and, later, tax harvesting for the dying Mughal Dynasty. In just under a century, they were the rulers of India.

George Santayana cautioned, ‘if we do not remember the past we are condemned to repeat it.’ Pakistan cannot afford to prove Mr Santayana right. The stakes couldn’t be higher.

The writer has been associated with media and the social sector.He tweets @hadesinshades