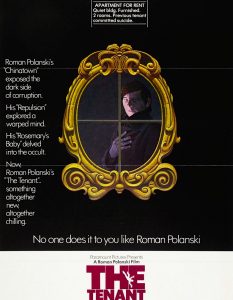

Classic Movie Review: The Tenant

By Ali Bhutto | Published 8 years ago

A life filled with persecution has shaped Roman Polanski’s art. The death of his pregnant mother at the hands of Nazis in Auschwitz, the brutal slaughter of his pregnant wife, Sharon Tate, by the Manson Family, and a 40-year-long-running conviction for an unlawful liaison with an underage girl, have all found their way into his work, in the most sinister scenes of victimisation.

A life filled with persecution has shaped Roman Polanski’s art. The death of his pregnant mother at the hands of Nazis in Auschwitz, the brutal slaughter of his pregnant wife, Sharon Tate, by the Manson Family, and a 40-year-long-running conviction for an unlawful liaison with an underage girl, have all found their way into his work, in the most sinister scenes of victimisation.

What is less commented on, however, is the kind of sensibility he brings to his films — one that is quintessentially non-American and unlike anything else in Hollywood cinema.

The eerie soundtrack to the opening sequence of Polanski’s The Tenant (1976), unleashes the sense of paranoia that runs through the film, laced with the director’s trademark black humour. Polanski plays Trelkovsky, a Polish-French bachelor who moves into a creaky-floored Paris apartment, the previous tenant of which flung herself from the window. There is something odd about the building and its eccentric inhabitants, but we cannot quite put our finger on what it is. The previous tenant is still alive and hospitalised, albeit in critical condition after her attempted suicide, and Trelkovsky is disturbed that his rights of passage into a potential new home depend on her demise. But, as the concierge reassures Trelkovsky, “don’t worry, she won’t get better.”

We experience the world through Trelkovsky’s eyes; one in which his timid nature often results in him being overpowered and bullied into submission. The cinematography of Sven Nykvist — known for his collaboration with director Ingmar Bergman — portrays a hostile world in which the protagonist suspects elaborate conspiracies are being hatched against him. And like in other Polanski thrillers, we the audience reassure ourselves by clinging to the hope that it’s all in his head; that such evil schemes cannot be real.

Everything in the film stems from the protagonist’s persecution complex. We are uncertain whether the events that unfold are real or a figment of his hallucinating mind, as the narrative increasingly blurs the line that divides the two. Trelkovsky is convinced that those with whom he shares the building are trying to drive him to commit suicide, like they did the previous tenant.

There is an iconic scene that aptly portrays Trelkovsky’s paranoia. Awakening from slumber, he looks out the window (from which the last tenant had flung herself), and finds the alleged conspirators, as suspected, seated in the courtyard like it were an opera house. One of them — posing as the victim — is wearing a mask of Trelkovsky’s face, and is about to receive a lynching, having been rounded up with pitchforks. But once they all spot the real Trelkovsky, they excitedly anticipate that he will let destiny take its course and jump from the window, which for them would be the climax of ‘the show.’ This is Polanski humour at its darkest.

The writer is a staffer at Newsline Magazine. His website is at: www.alibhutto.com