Will India Accept Modi?

By Sujoy Dhar | News & Politics | Opinion | Viewpoint | Published 14 years ago

Tamas (Darkness), created by one of the most accomplished art-house filmmakers of that time, Govind Nihalani.

Tamas (Darkness), created by one of the most accomplished art-house filmmakers of that time, Govind Nihalani.

It is an improvised version of the original, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to fulfill it,” an aphorism coined by George Santayana, a Spanish-American philosopher and writer who died in 1952. Every episode of Tamas would start with this universalised expression, reminding us not to prolong the burden of history with more mistakes.

Tamas is the story of a poor lower-caste couple caught in the vortex of the partition of the Indian subcontinent and the dark days of 1947 — when the two new nations were badly singed by Muslim-Hindu-Sikh communal riots. Tamas is based on a book by Brisham Sahni, who also went through the throes of Partition, was uprooted from West Punjab and came to live in India as a refugee.

The story of Partition has been heard in every Indian and Pakistani home after 1947. My parents would tell us about the travails of my grandparents, who were uprooted from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). The poignant stories of Saadat Hasan Manto that I read provided a similar historical flashback and were a touching reflection of that time. So when Tamas was telecast by Doordarshan in India, it provided food for thought to our generation, left a deep impact, moved us emotionally and warned us against the dangers of stirring the communal cauldron.

But, time and again, we in secular India failed to take those warnings seriously. In 1984, we saw the anti-Sikh riots that followed Indira Gandhi’s assassination and, soon after that, we were shocked by the Babri Masjid massacre in 1992 where ensuing riots across India and Pakistan killed over 2,000 people. And, in 2002, we wrote another shameful chapter in the annals of communal hatred — this time in the state of Gujarat, in the wake of the Godhra train burning. After 59 Hindu religious volunteers (known as Kar Sevaks) were burnt alive, riots ensued in Gujarat.

Unfortunately, Muslims bore the brunt of these horrific riots that were said to be patronised by some of the leaders of the ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its ideological cousins. At the time, the BJP government in the western state was then, and also now with additional strength, led by chief minister Narendra Modi, who is said to have turned a blind eye to these riots that took a heavy toll on the Muslims of Gujarat.

Nine years later, Narendra Modi has become one of the most successful chief ministers of India. He has turned Gujarat into a showpiece of India’s development and progress, attracting investments like never before and curtailing discrimination against Muslims by pursuing a policy to allow them to develop and prosper — a fact that they acknowledge at every public forum.

Despite all this, he may still continue to pay the price for 2002, especially now, when an apparent Supreme Court reprieve to Modi in the riot cases has emboldened him to eye a prominent national role.

Modi is a strong contender as a prime ministerial candidate in the BJP ranks for the next general elections in 2014. Importantly, the buzz around his projection as the future prime minister of India receives strong endorsement from the USA, which had so far continued to deny him a visa, following the 2002 riots.

But now, a Congressional think-tank in the USA hails Modi as a role model for development in India. A report on India published by the Congressional Research Service (CRS), which works exclusively for the US Congress to provide policy and legal analysis to committees and members of both the House of Representatives and the Senate regardless of party affiliation, predicts that Modi’s bid to run for election may pitch him as a strong prime ministerial candidate in India’s 2014 election. The report also forecasts that BJP’s Narendra Modi may be pitted against Rahul Gandhi of the Indian National Congress in the next elections. Incidentally, the report is not as charitable to Gandhi as it is to Modi.

To redeem his political image Narendra Modi took a leaf out of the modus operandi of Gandhian social activist Anna Hazare and decided to sit for a token three-day fast to spread the message of communal harmony. On September 17, the day he turned 61, Modi began his fast at the Gujarat University exhibition hall, termed the ‘Sadbhavna Mission’ (Communal Harmony Mission), to appease religious communities in India. He broke his fast by drinking juice given to him by the clerics of three major religious faiths — Hindu, Muslim and Christian.

Party leaders like the BJP patriarch, L.K. Advani, as well as Arun Jaitley, showered praises on Modi. He also garnered support from those outside his own party, the chief ministers of India’s two key states: Tamil Nadu’s J Jayalalithaa, who spearheads the southern outfit the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK), and Punjab’s Parkash Singh Badal, who belongs to the Shiromani Akali Dal party. BJP’s bid for power is also dependent on the support of its coalition partners in the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), which includes parties largely supported by Indian Muslims.

But protest over Modi’s posturing came first from the Janata Dal (United) leader, Nitish Kumar, also a game-changer in current Indian politics having turned around Bihar, the country’s most lawless state. The party’s spokesperson Shivanand Tiwari berated his eligibility to lead a country of 1.21 billion people when he failed to perform his rajdharma (duty as a leader) in Gujarat.

Modi also faces strong resistance from several civil society groups in Gujarat. Actor-dancer and known anti-Modi social activist, Mallika Sarabhai, naming specific people and law firms, revealed that the chief minister tried to bribe her lawyer to gather information on the activists’ legal strategies in the riot cases that are filed against him in the Supreme Court.

With the odds stacked against him, the big question is: if the BJP returns to power, will Modi, a new brand in Indian politics, ever become the prime minister of India?

Suhel Seth, a social and political commentator, believes that after the Gujarat blemish, people have moved on, and so will Modi, elaborating that he is not the only politician in India accused of communalism — after all the Indian National Congress was the main architect of the anti-Sikh riots in 1984.

While a debate rages on about Modi’s acceptance as a national leader, the political reality of 2014 will have the last word. And that is still many, many, months away.

The Nawab of Cricket

The Nawab of Cricket

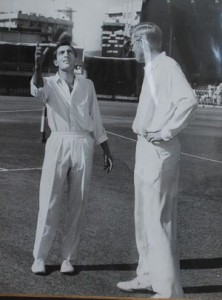

September was a month of mourning for cricket lovers in India. The royal era of Indian cricket came to an end on September 22, when India’s first superstar cricketer and the youngest captain of the Indian cricket team, Nawab Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi, popularly known as ‘Tiger’ Pataudi, passed away at the age of 70 in New Delhi after battling a lung infection for over a month.

Long before cricket became the stuff of big business superstars, Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi blazed a glorious trail with the willow and the leather, and was one of the few dashing men worshipped across the subcontinent.

Between 1961 and 1975, Pataudi played 46 Test matches for India, he captained 40 of these 46 Test matches, out of which India won nine. He became a living legend for his ability to play with one eye. In 1961, when he was only 20, a car accident permanently damaged vision in his right eye. And just a few months after the accident, he made his international debut against England and went on to score a classy 103 in a Test match.

Pataudi’s cricketing career was imbued with the stuff of legend when on March 23, 1962, at the age of 21 years and 79 days, he became the youngest cricketer to captain any country in a Test match. A nasty injury to then captain Nari Contractor, who had to undergo brain surgery after being hit by a Charlie Griffith bouncer, changed Pataudi’s fortunes and he was appointed India’s captain for their tour to the West Indies.

Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi was born in 1941, in the central Indian state of Bhopal, to former Indian captain and the eighth Nawab of Pataudi, Iftikhar Ali Khan, who also played for England, and Sajida Sultan, second daughter of the last ruling nawab of Bhopal.

He was the first cricketer to date a Bollywood actress and he went on to marry the most refined and daring Bollywood heroine of the 1960s, Sharmila Tagore. The couple have three children: daughters Soha Ali Khan and Saba Ali Khan, and son Saif Ali Khan, a Bollywood superstar.

A heady concoction of royalty and extraordinary talent, the handsome Pataudi was the stuff that romantic novels are made of. In the weeks following Pataudi’s death, the global cricket fraternity and cricket fans around the world continue to pay glowing tributes to this prince among men.