Bringing Solutions to the Table in Afghanistan

By Ayesha Siddiqa | News & Politics | Published 14 years ago

If you are a journalist or a political commentator, you are certain to get frantic calls from friends and family inquiring whether there will be a war between Pakistan and the US. The recent increase in tension between Pakistan and the US is unprecedented as both allies appear poised to come to blows with each other — or at least this is the common perception on the streets of Pakistan. There is concern in the country’s policy-making circles as well; they are considering a whole range of possibilities from an increase in American drone attacks to additional surgical strikes inside Pakistan, such as the one on Osama Bin Laden’s compound on May 2. There are fears too of American boots on the ground, which will naturally be viewed as a clear violation of Pakistan’s sovereignty.

If you are a journalist or a political commentator, you are certain to get frantic calls from friends and family inquiring whether there will be a war between Pakistan and the US. The recent increase in tension between Pakistan and the US is unprecedented as both allies appear poised to come to blows with each other — or at least this is the common perception on the streets of Pakistan. There is concern in the country’s policy-making circles as well; they are considering a whole range of possibilities from an increase in American drone attacks to additional surgical strikes inside Pakistan, such as the one on Osama Bin Laden’s compound on May 2. There are fears too of American boots on the ground, which will naturally be viewed as a clear violation of Pakistan’s sovereignty.

Nothing seems impossible considering the rising American rage over Pakistan’s alleged cooperation with the Haqqani network and the ISI’s alleged involvement in the attack on the American embassy in Kabul. Recently, Admiral Mike Mullen, who always regarded himself as a friend of General Ashfaq Pervez Kayani, a few days prior to his retirement as chairman of the US joint chiefs of staff, went on record to accuse Pakistan of collusion with the Haqqanis. Although other American policy-makers were subsequently more cautious, Mullen’s comments, which he made while testifying before the Senate Committee in Washington, resonated on Capitol Hill. Needless to say, these comments did not do much for either American or Pakistani interests; rather, they brought the two sides to what looks like a collision course.

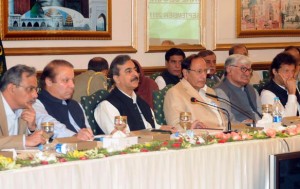

The Americans claim to have evidence of Pakistan’s involvement in the attack on the US embassy in Afghanistan, a charge that was denied by the ISI chief, General Ahmed Shuja Pasha, during his briefing to the All-Parties Conference on September 29. Earlier, Major General Athar Abbas, the ISPR chief, had stated that Pakistan’s ISI had nothing more than some contacts with the Haqqani network, but then so did numerous other agencies.

The entire focus of the bilateral dispute seems to be the Haqqani network, which is a group of the Taliban that have shown tremendous capacity to attack the US forces inside Afghanistan with impunity. The network comprises Sirajuddin Haqqani, son of the Afghan veteran warlord Jalaluddin Haqqani, Mullah Nazeer and Hafiz Gulbahadur. Although these warlords hail from Afghanistan, they have, over they years, managed to operate from Pakistan’s tribal areas and use it for re-grouping purposes or what a friend terms “rest and recreation.” The Haqqani network remains an “old irritant” in Washington circles. Prior to the Swat military operation, the US had been insisting that the Pakistan army target the Haqqani network, which appeared to control the areas bordering Afghanistan. But the Pakistan army always maintained that it would not antagonise any group that did not attack the Pakistani state. Additionally, Islamabad was peeved that the US was very selective and that it did not target those forces in Afghanistan that hurt the Pakistani state despite the evidence provided by Pakistan.

However, when a known enemy like Baitullah Mehsud was killed in a drone attack, Pakistan was not comfortable with the US policy of drone strikes. Some analysts are of the view that drone attacks pose a major threat to the Taliban, and one wonders if the Pakistani state’s main concern is collateral damage caused to innocent victims or the safety of Taliban groups that are considered friendly by the army and the ISI. In any case, numerous military analysts who are also linked with the ISI and the military, such as Brig. (retd) Asad Munir and Lt General (retd) Asad Durrani, consider the Taliban as representing almost 90% Pashtun interests. A similar claim is also made for the Haqqani network, which is viewed by the Pakistani state as representing Taliban interests. This perspective came out very clearly in a recent report published by Pakistan’s Jinnah Institute and America’s United States Institute for Peace (USIP). The analysis in the report, which was based on the point of view of 53 analysts, most of whom are known to sympathise with the state perspective, equate Taliban interests with Pashtun interests. This report is important since it indirectly presents the Pakistani military establishment’s perspective. Prime Minister Yusuf Raza Gilani endorsed this standpoint by announcing that Islamabad will talk to the Haqqani network as well.

The present friction is a consequence of the initiative on both sides (the US and Pakistan) to influence the Afghan endgame to their respective advantage. Privately, retired and serving military officers and strategic experts, who are now in abundance in Islamabad, admit that the ISI supports the Haqqani network due to its ability to launch military operations inside Afghanistan. These attacks are meant to bring the situation to a point where the US agrees to include Haqqani in the negotiations, the same way that Washington is talking to Mullah Omar. Lately, there were also reports that some of the military operations carried out in the last three to four months in South Waziristan were to allow room for the Haqqani network to operate in the South and engage with the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). According to this plan, a friendly tribal force would manage to eliminate or neutralise an unfriendly tribal army more effectively.

There is no doubt that the Haqqani network keeps moving across the border, but its use of Pakistani territory as a staging post has never really been a secret. There are three Taliban groups: the Sirajuddin Haqqani group represents a Pakistan-friendly force as does the Quetta Shura but the TTP is considered inimical to Pakistan’s interests. For the moment, the Pakistani military is keen to put all its eggs in the Haqqani basket, in the hope that the Haqqanis inclusion in any future dispensation in Kabul would ensure a Pakistan-friendly government in Afghanistan.

But pursuing this game is not as easy as it sounds. First and foremost, there is the issue of American perception and reaction to the plan. The US has continued to launch drone attacks in North Waziristan to put pressure on the Taliban, in order to be able to negotiate with them from a position of strength. Although the Pakistani media has decreased its reporting of drone attacks after May 2, there has never been a lull in these attacks. If the US intends to up the ante, it could only do so by conducting a May 2 kind of a strike, but that is not possible without the availability of specific and actionable intelligence. Besides, there is always the risk of Pakistan responding to a surgical strike, which the army claims it would resort to the next time round. A Pakistani response would bring the army in direct confrontation with the US, which both sides might try to end to their own advantage. The political costs of such an adventure would be high for both sides and would not bring any real strategic benefits. The US must understand that the possibility of a military defeat may not, at this stage, convince Pakistan to take on the Haqqani network.

But pursuing this game is not as easy as it sounds. First and foremost, there is the issue of American perception and reaction to the plan. The US has continued to launch drone attacks in North Waziristan to put pressure on the Taliban, in order to be able to negotiate with them from a position of strength. Although the Pakistani media has decreased its reporting of drone attacks after May 2, there has never been a lull in these attacks. If the US intends to up the ante, it could only do so by conducting a May 2 kind of a strike, but that is not possible without the availability of specific and actionable intelligence. Besides, there is always the risk of Pakistan responding to a surgical strike, which the army claims it would resort to the next time round. A Pakistani response would bring the army in direct confrontation with the US, which both sides might try to end to their own advantage. The political costs of such an adventure would be high for both sides and would not bring any real strategic benefits. The US must understand that the possibility of a military defeat may not, at this stage, convince Pakistan to take on the Haqqani network.

The greater risk Pakistan faces is that of economic sanctions. The Pakistani establishment is trying hard to find alternative economic sources such as China, or by increasing trade options. But none of these have the potential to offset the damage if the US were to rally the world to punish Pakistan economically. From this perspective, the All-Parties Conference convened by Prime Minister Gilani to deal with the situation failed to do a satisfactory job. While the APC was high on expression of national anger, it did not really look at the various scenarios that Pakistan may have to encounter. Also, the meeting did not highlight the fact that there is little that Pakistan can do in terms of convincing the US to accommodate the Haqqani network. However, the APC uproar has somewhat eased Washington’s pressure on Pakistan. They have toned down their accusations, even though a large number of American policy-makers are not convinced of Pakistan’s innocence vis-Ã -vis the Taliban.

Another problem with the APC was its inability to emphasise the need for an alternative agenda to counter radicalism, terrorism and Talibanisation in Pakistan, and in the region. GHQ Rawalpindi, as sources suggest, feels that after the American exit from Afghanistan, violence in Pakistan and the region in general will dissipate as the Afghan Taliban, including the Quetta Shura and the Haqqani Network, will move back into Afghanistan. The Pakistani groups, on the other hand, such as the Lashkar-e-Taiba or various other Deobandi groups, will either take their activities to the tribal areas or keep moving between Afghanistan and the tribal areas. It is generally believed that in either case, Pakistan will see less violence. A friendly government in Kabul will ensure peace in Pakistan. But this formula does not necessarily guarantee Pakistan’s security or solve its radicalisation problem. Furthermore, with so many factions in Afghanistan, there is a risk of Pakistan getting sucked into the Afghan quagmire. After all, if you rush to get to the head of the table, there is also the risk of being the first to face the music. Supporting the Taliban and similar groups is a strategy fraught with huge security risks for Pakistan’s stability in the future.

The current showboating between Pakistan and the US does not serve the interests of either. The best option for Afghanistan would be for all players in the region to come together to ensure the country’s immediate security and find a solution to its future problems. Besides America’s dependence on Pakistan to keep its supply lines to Afghanistan open, there are strategic reasons for Washington to keep talking to Islamabad. But as the US gets into the election cycle and its enthusiasm for staying on in Afghanistan wears out, chances are that the hawkish elements in Washington may increase the pressure on Pakistan. This is the time for various forces involved in Afghanistan and in the region to move with caution and show sense and sensibility, without which they will not be able to bring a solution to the table.

Related Post:

Double Games People Play by Rahimullah Yusufzai: With Pakistan, the US and Afghanistan pointing accusatory fingers at each other as the US withdrawal from Afghanistan nears, how will ‘The Great Game’ in the Af-Pak region end?

This article was originally published in the October 2011 issue of Newsline under the headline “From Here to Where?”

The writer is an independent social scientist and author of Military Inc. She tweets @iamthedrifter