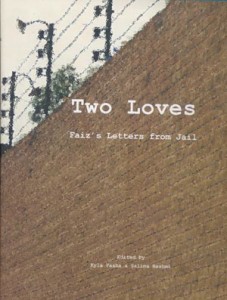

Book Review: Two Loves – Faiz’s Letters from Jail

By Tehmina Ahmed | Arts & Culture | Books | Published 14 years ago

The Personal and the Political

Among the treasure trove the Faiz Centennial brought us is Two Loves, a collection of letters written by the poet to his wife, Alys, during the early ’50s. While an Urdu translation of the 135 letters written during the poet’s incarceration titled Saleebain Mere Dareechay Main was published in 1972, the original English text has just seen the light.

The original letters had been damaged by a termite attack while Faiz and Alys were away from home in Beirut. It was thought that they were lost, but Salima Hashmi, the poet’s daughter, says she accidentally “came across a plastic bag containing some scraps of paper.” On closer examination, they seemed to be the jail letters. She credits archaeologist Dr Asma Ibrahim for the conservation of 24 of the letters. Kyla Pasha, who co-edited the publication with Salima, deciphered and transcribed them for publication.

Two Loves begins with two prefaces to Zindaan Nama — a collection of verse written and published during Faiz’s imprisonment — by Major Ishaq and Syed Sajjad Zaheer, two of his fellow ‘conspirators’ in the infamous Rawalpindi Conspiracy case.

The book reproduces portions of the retrieved letters in Faiz’s hand, along with the transcribed version. It includes letters from daughters Meezu (Muneeza) and Cheemie (Salima), then four and eight years old respectively, to ‘Dearest Abba.’

The Urdu translation of the letters for Saleebain was written by Faiz himself at the behest of his friend and admirer, Mirza Zafar-ul-Hasan of the Idara-e-Yadgar-e-Ghalib. Initially reluctant to undertake the project, Faiz eventually came up with a translation that would have been truly difficult for another writer to match. While the English letters are the real thing, the Urdu translation is, in itself, a pleasure to read for the sheer fluidity of the prose. It did, however, differ from the original in some ways, and the difference was not due to the exigencies of translation alone.

To speed things up when the translation was proceeding too slowly, Faiz suggested that some repetition and matter considered redundant be excluded from the Urdu version. Some passages of a personal nature were also excluded or condensed.

It is a great tragedy that only 25 of the original letters survived, but their publication in the original form sheds a new light on the poet, who could be as enigmatic in his personal life as he was open in the writer’s persona. There are intimate moments here, glimpses of a man who was truly devoted to his wife and children and suffered great anguish during his incarceration, not so much for the restraint it placed on his own self as for the toll it took on his near and dear ones.

For the very private man it must have been difficult to write these personal letters, knowing that every word would encounter the censorial eye. For all that, the letters are completely devoid of self-consciousness, many written in a cavalier strain that makes little of the privations of prison life.

Incoming letters, too, were censored and the ridiculous nature of the exercise is nowhere more apparent than in a letter bearing Muneeza’s first and somewhat tipsy efforts to write out numbers and the alphabet. It bears the stamp of the Registrar of the Rawalpindi Special Tribunal.

The thought that runs through the letters is echoed in the poems of the period, so for Faiz one could truly say that the personal and political were not separate. The poetry of the period is an exhortation to struggle, but the struggle is never grim. In Faiz’s letters, too, he emphasises that it is not enough to struggle against the dark side, one must do so in good cheer.

Making an interesting distinction between pain and unhappiness, he says that pain comes from without, an imposition from an often unkind world. “Unhappiness, on the other hand, although produced by pain, is something within yourself which grows, develops and envelops you if you allow it to do so and do not watch out.” Thus pain is unavoidable, but “unhappiness you can overcome if you consider something worthwhile enough to live for.”

Obviously there was much to live for, as the letters bear witness. From the plants growing in a prison garden to the company of friends, the much anticipated visits of family and, above all, the courage of his convictions that remained unchanged throughout the trying period.

There are cameos of family life. Alys, who cycles to work at 6‘o’clock in the morning still has time to take Meezu’s khargosh (rabbit) to the hospital with an injured leg. Salima writes about dancing with her cousin Maryam for Red Cross week. There are the domestic details: warm clothes and razais come and go. Faiz asks for “small teapot covers,” writing, “I don’t think there is anything else that I want except you and the pigeons.”

In another letter written from Hyderabad jail in the thick of the summer he says, “Heat and dirt, and prison walls can all go to hell.” This is the sentiment that resounds throughout the book, while the warm and caring spirit of Faiz comes through on every page.

This book review originally appeared in the October 2011 issue of Newsline under the headline “The Personal and the Political.”