Interview: Nida Bangash

By Maheen Bashir | Art | Arts & Culture | People | Q & A | Published 14 years ago

“To put it literally, we are all ‘blacks’ and carry the same ‘wool’ which ‘Sir’ always wants!”

– Nida Bangash

Nida Bangash was born in Mashhad, Iran and after graduating from Lahore’s National College of Arts with an Honours MA degree in Visual Arts, Nida then went on to secure a diploma from Princes School of Arts in London. ‘Black Sheep’s Wool’ is Nida’s second two-person show, but she has participated in other group shows in London, Dubai and India. At present, Nida lives between Lahore and Mashhad.

The exhibit titled ‘Black Sheep’s Wool’ was assembled after your return from Madagascar and contains snippets from everyday life there: the chilies, local children and even a King Julian stamp. What was the inspiration behind this project?

Yes, most of these art works were envisioned and created in Madagascar where, at first, I thought the only thing I had in common with them was my hair colour! But this premature idea fizzled out soon enough. I stayed there for three months and all I would do was wander the streets, observe and interact with people, take photographs, read, paint and write letters. It didn’t take long to realise that Malagasies and we (Pakistanis) meet at so many levels. Both fall into the so called ‘Black’ category and carry colonial baggage — although we had different rulers of course. Malagasies were colonised by the French and we were ruled by the British. This formed the basis of my work and I built on it from there.

About King Julian, I painted a ring-tailed Lemur and it’s a great coincidence that King Julian in the animated cartoon Madagascar happens to be a Lemur.

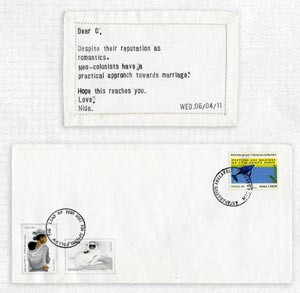

In your first installation there are 12 diptychs: one-line letters on cotton napkins juxtaposed with paper envelopes. At first glance they sound wistful, musings addressed to an intimate friend, but the narrative contains serious comments on the socio-political situation. What is the message and why choose this medium to convey that message?

Well, the basic format of this body of work comprising letters, envelopes and stamps comes from the travelling experience and refers to communication. Making stamps is such an ‘outsider’ thing to do, I suppose, but it captures the way the insiders (locals) are perceived. A dear friend recommended that I read Manto’s letters to uncle Sam and that also struck many chords in my head. The choice of using cotton napkins as the base for these letters is an act of connecting my work to the dining experience, which my husband and I were exposed to quite frequently in Madagascar. Quite often we tend to act “whiter than whites,” and my work focuses on this irony at one level while aiming to chart out and inhabit the similarities and differences of skin, race, language and appearance, at another.

In the themes of your work, you explore racial discrimination and the colonial hangover. Were you drawing parallels with Pakistan, especially when you say, “At least they gave us a railway that still works,” and “I think the English were better colonisers than the French?”

Of course! Being in another previously colonised country made me realise how colonised I still am. I was continuously trying to analyse and compare what we have in common, to the point where I considered us as a nation very close to them. To put it literally, we are all “blacks” and carry the same “wool” which “Sir” always wants!

You ruminate on the neo-colonialist mindset in Madagascar. Does it stem from a personal experience there?

It definitely evolves from different experiences I had in Madagascar, but the term neo-colonist here has a more general meaning.

Do your photographs, displayed as stamp sheets, carry the same train of thought as the letters?

Yes, while making a body of work, I try looking at it as a whole.

In your second installation of photographs and stamps, painted onto the envelopes, there are images of old cars, and black and white sketches of workers. Is the historical sense imbued in the installation deliberate?

Yes, this work tends to travel back and forth. I’m looking at so many issues catered to, yet overlooked over the passage of time. So, it is nostalgic yet relevant to modern times.

“Bon Appétit. Follow the lead of your host” is stamped on the envelopes. Can you explain that?

“Follow the lead of your host” is the first rule of French dining, as you may know. The French are very particular about the dos and don’ts when dining, and they have the most extraordinary rules that they strictly adhere to and expect others to follow. Ironically, perhaps the French forgot their rule to “follow the host” as colonisers. It’s just a little take on that, hence I chose to use embroidered cotton napkins instead of paper for the letters.

You live between Lahore and Mashhad, Iran. How does that influence your work?

I belong to part-Iranian parentage. I was born in Mashhad and I continue moving in and out. This experience helps me look at my art practice, especially miniature painting, in a unique way. One sees a beautiful unification of Persian and Indian paintings during the Mughal era, and what I enjoy most in the art produced during that period is the celebration of many visual cultures it embodies. Here, I am luckily wedged between the very same ‘loaded’ cultures and I often find solutions to many creative hitches in the history which I’m part of.

Well, I don’t fit in any box; my work is usually interdisciplinary. I experiment with a lot of mediums: drawing, painting, video, installation, photography and so on. Yes, I do work as a photographer for PCTV, and I’m learning a great deal from it, but at the same time I give time to my studio.

Do you plan to do more projects like these in the future?

I’m definitely going to continue my art practice and, as always, it’s going to keep evolving and taking on new forms.

What does art mean to you?

Art for me is a tool that I have been trained to use. I have been using this tool to communicate over the years, and it often helps us to communicate with certain groups we can’t reach otherwise. I think in this particular case (‘Black Sheep’s Wool’) my camera captured elements that I did not realise were so important at the time. And my travelling to Madagascar and finding similarities and differences between us and them became so overwhelming that it had to be communicated forward.

Maheen Bashir Adamjee is an APNS award-winning journalist. She was an editorial assistant at Newsline from 2010-2011.