Labour: The Unkindest Cut

By Deneb Sumbul | Newsline Special | Published 8 years ago

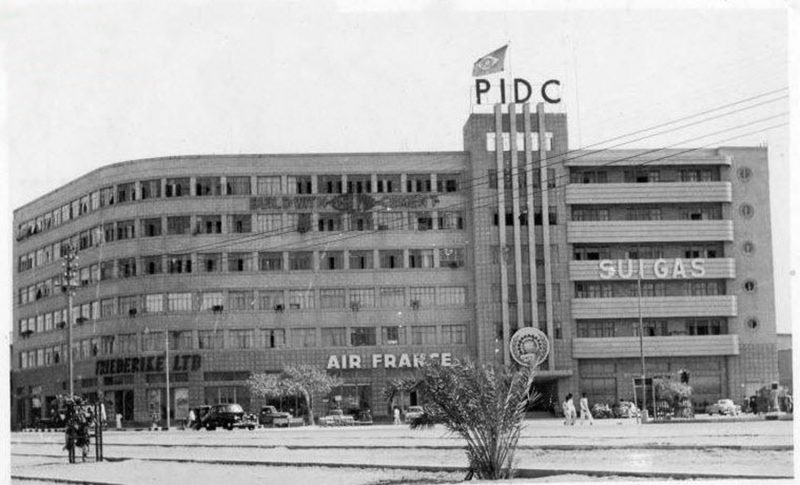

Burgeoning industrialisation in the 1950s under the PIDC left little scope for social benefits for labour and factory workers.

Only 15 per cent of the people cast their vote in the 1946 provincial elections of British India. However, these elections united the Muslim vote, with them winning nearly one third of India. This in turn empowered the Muslim League to begin negotiations for the partitioning of India. However, the ordinary man did not have the right to cast his vote. That privilege was extended only to those who paid income taxes or owned estates.

This set the pattern for the new country that continues, with only a few modifications, to this day. After Partition, a migrant working class developed that was multi-ethnic but being displaced, they had no connection with the locals. Simultaneously, there were workers migrating to Karachi from the rest of Pakistan who also had no connection with Sindh’s peasantry. As a consequence, in Karachi — the country’s industrial hub — employers would hire assorted ethnic worker groups to ensure they would not unite or unionise to their bosses’ detriment. Interestingly, the industrialists were not local either. Thus, in the 10-15 years of burgeoning industrialisation that took place in the 1950s in Karachi, not even five percent of the labour force was organised. And the Sindhis were not part of the industrial labour force.

In 1952 with a bid to kickstart industrialisation in the new country the Pakistan Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC) was set up. Hand-picked industrialists — were given a host of concessions to run industries, factories etc. These business families were given loans on the easiest of terms by the government, and in many cases factories were given to them almost free. This lead to the creation of the 22 wealthiest families of Pakistan, with a sizeable chunk of Pakistan’s assets and wealth coming under the hegemony of just a few — and the trend persists.

Over the next decade the PIDC established a total of 94 industrial units during 1952-1988, 21 of which were in East Pakistan with the plan to later sell them to the private sector.

However, the terms for the transfers of these establishments to the private sector were unknown.

Since the government of the day was more interested in modernising industry than on people’s basic needs, progress everywhere apart from the industrial sector, was stunted. Unable to find jobs in their villages, people started migrating to the big cities, while even medium-size cities were neglected.

Of all the international advisors consulted, the Harvard Advisory Group in particular was of the opinion that if Pakistan was to progress, it should go into large-scale manufacturing. General Ayub Khan’s government adopted internationally renowned economist, Dr. Mahbub ul Haq’s philosophy: that Pakistan’s economy was too small, and if social objectives like equity and labour laws, etc. were factored in, the industrialists and businessmen would not be able to accumulate enough finances to re-invest in factories.

Field Marshal Ayub Khan had taken over the reins of power in 1958, and the rapid industrialisation in the country continued. However, the workers operating these concerns and labour in general were prevented from organising themselves into strong, cohesive unions, because of the self-serving interests of the four classes who established relationships between themselves and banded together — namely the feudals, the bureaucrats and the generals. And soon thereafter, the mullahs too became part of this unholy alliance. Unlike other societies, Pakistani industrialists too were, in favour of a state which kept workers under their control, thereby allowing them to maximise their profits.

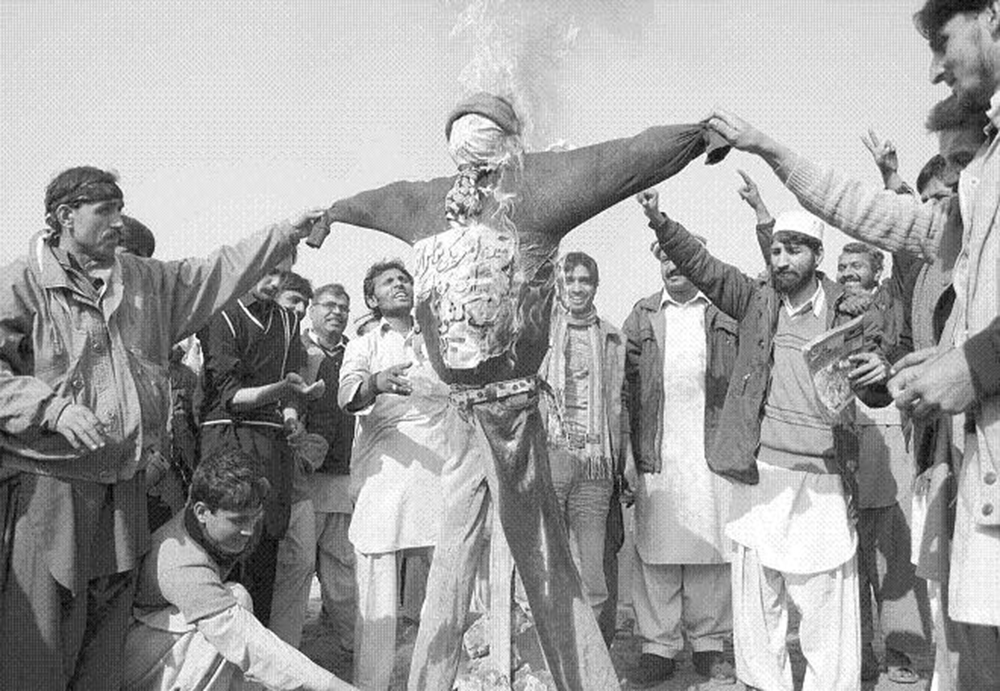

Under military governments, trade unions and workers’ movements are invariably crushed with force. General Ayub Khan’s Martial Law was no different (1958-1969). All unions were abolished and a new Labour Policy was introduced which did not include Freedom of Association. Many people were also arrested.

It was 10 years before a mass movement — of which labour was a cornerstone — removed Ayub from office in 1969. General Yahya Khan assumed power after Ayub Khan’s ouster and the new military junta called a labour conference to work on a fresh labour ordinance. As a result of the struggle by labour against the unfair treatment being meted out to workers another Labour Policy was promulgated in 1969 — an Industrial Relations Ordinance. It recognised that workers’ rights had been usurped and that the state had not accepted the responsibility of protecting even their basic rights.

This interesting document was credited to Nur Khan, the Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Air Force and Deputy Martial Law Administrator (1965-69) who was in charge of labour and, despite his official positions, had a progressive stance.

The Industrial Relations Ordinance favoured a trade-union policy that encouraged negotiation between the labourers and the industrialists instead of confrontation, and was critical of the previous labour laws and practices. The ordinance injected new energy into the labour movement and unions came to life; taking advantage of the clauses, the workers started demanding bonuses, better working conditions and back pay. However, the military government of the time remained committed to preventing strikes and lockouts and gave the industrialists carte blanché in hiring and firing decisions. And regardless of the Ordinance, arrests of labour leaders, workers and activists continued unabated. An estimated 45,000 workers in Karachi alone were retrenched during Yahya Khan’s tenure (1969—1971).

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto came into government in 1970 through the power of the people because he spoke of a people’s agenda and promised roti, kapra aur makaan. Initially, he did attempt to introduce a few reforms. The nationalisation process started by Bhutto was welcomed by the masses. He introduced labour laws that made industrialists responsible for the welfare of their labourers and their families, and provided them employee benefits. However, a close of examination of that period reveals that the real cause of damage to the labour and trade union movements was the legislation at the time.

During Bhutto’s administration, the talk of a planned economy and nationalisation became double-speak for bureaucratisation. Factories were handed over to corrupt officials, and, in many cases, the factory owners were made managers. A negative trend in politics began when it was considered acceptable to pilfer goods belonging to the government. Corruption extended to the lowest level when political workers were bribed with contracts, licenses, and sugar depots. People in the trade unions were also bribed and compromised in the same way.

Bhutto’s government developed the Labour Department but the Labour courts did not fall under the purview of Pakistan’s judiciary. And increasingly, Bhutto appeared to be at the crossroads — between the millions who had rallied to bring him to power, and those whose company he kept. The elite, the feudal lords and the powerful business community said he was doing too much for labour and the working class, while those he spoke for said he was doing too little. Caught between the two, he ultimately tilted towards his own social peers.

In the first half of 1972, periodic lockouts and encirclements of factories continued in Karachi’s two major industrial areas. Workers were demanding the reinstatement of those retrenched during the Martial Law years, demanding back pay from industries that had closed without notice, compensation, distribution of bonuses, and payment into workers’ participatory funds. In 1972 the labour movement upsurge again witnessed a particularly brutal quelling during Bhutto’s government. Workers were brutally killed, put into jail by the thousands and shameful tactics were employed at police stations where men and women trade union activists were allegedly sexually assaulted. People were especially deployed to conduct such horrific crimes.

In 1977, when Bhutto’s government was overthrown by General Zia-ul-Haq, another decade of Martial Law followed and saw a period of extreme repression in which trade unions and political parties were harshly clamped down on and selected trade union activists and leftists were systematically killed.

Perhaps one of the most brutal acts of Zia-ul-Haq’s dictatorship, was the massacre of workers’ Colony Textile Mills in Multan in January 1978. Workers had begun a ‘tools-down’ strike to protest the non-payment of annual bonuses that were due to them after the reforms of 1969 and 1972. Under Zia’s orders paramilitary forces opened fire on the peaceful protest. At the end of the operation it was estimated that close to 200 workers had been killed and twice that number injured. However, according to eye-witnesses, the fatalities were much higher, the corpses of the others having been thrown into the industrial nullah in the area by the forces conducting the operation.

Zia introduced the Hudood Ordinances, and a variety of other religious measures, including the Zakat and Salat (prayer) committees. Intelligence personnel from these would ‘visit’ factories to check whether people were offering the now mandatory Zuhr prayers. This was a period of extreme corruption and harsh reprisals for any perceived anti-government activity. It was very difficult for women to come out into the street. In the ‘60s and early ‘70s, women had become mobilised in the unions. Several had become union general secretaries and presidents, and then the overall regression set in.

Before Zia-ul-Haq, Pakistani society was rapidly heading towards a kind of liberal capitalism, but during Zia-ul-Haq’s regime, all concepts and aspirations for a welfare state were discarded, as theocracy was given official sanction. Those who ran madrassahs, for example, were allegedly inducted into the country’s civil services.

The contract system that was introduced during Zia-ul-Haq’s regime greatly weakened the workers’ movement and organisations. He disallowed factory inspections without the employer’s permission. As per the Factories Act, factories were required to be inspected annually to check whether health and safety standards were being maintained. The General saw the Labour Laws that afforded workers a degree of protection, as obstacles towards the free market. When a campaign began by the trade and labour unions against the contract system, representatives from the American Embassy in Islamabad requested to meet with trade union leaders in their Karachi office. At the meeting, the US Embassy officials advocated the contract system, saying that for rapid economic development in Pakistan, the only way forward was to bring in foreign investment. Therefore, they advised, the labour union representatives should not campaign against the contract system, otherwise no foreign investment would come in.

Thereafter was launched a major populist movement based on a left-wing political alliance against the military government of President General Zia-ul-Haq. The Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD), included students, trade unions and political parties. It was said to be one of the most massive non-violent movements in South Asia since the time of Gandhi, but even so, it could not extend its outreach beyond Sindh. The government responded as dictatorial regimes are wont to do in the face of opposition: thousands of workers were jailed and cases were lodged against them. And then in a bizarre twist of fate, General Zia was killed in an air crash, following which the MRD alliance was dissolved, paving the way for general elections.

During the resultant interim government, no Prime Minister was put in place, even though Pakistan’s constitution clearly states that a caretaker Prime Minister has to head any interim government. Instead, the state was, to all intents and purposes, run by the then Chief of Army Staff, General Aslam Beg. With Dr. Mahbubul Haq as one of the ministers, the interim government made an agreement with the IMF three days before the elections, under which certain structural adjustment programmes were implemented, including privatisation. Significantly, one of the conditions of the agreement was the deregulation of the labour market. Constitutional experts meanwhile, argued that the government which made the agreement on structural adjustment with the IMF was, in itself, illegal.

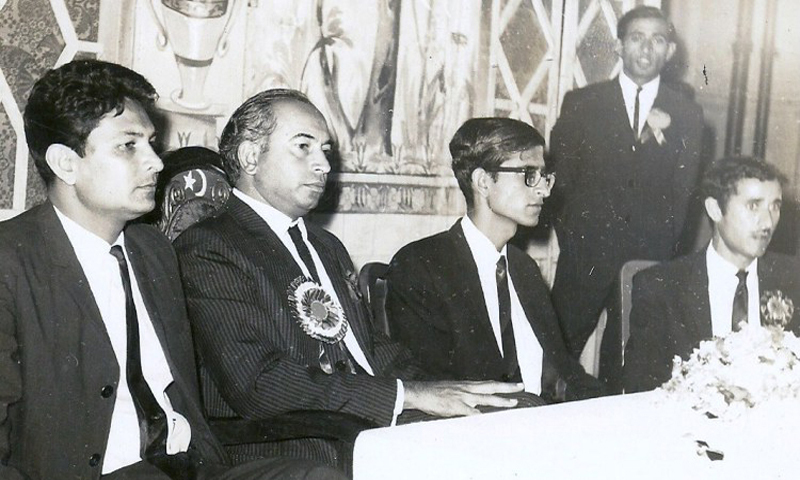

Z.A. Bhutto (centre) with the two top leaders of the National Students Federation (NSF), Mairaj Muhammad Khan (left) and Rashid Ahmed (right) at an NSF convention in Karachi (1967).

In the elections that followed in November 1988, the PPP emerged as the single largest party, but without a clear majority. The new government under Benazir Bhutto was either unable to, or reluctant, to implement the interim government’s labour and IMF and World-Bank-prompted policies. There is a theory that the charges of corruption levied against her administration was the excuse used to remove her from office in 1990 for not following through.

In 1990, a change of government ushered in Nawaz Sharif, and just as Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had nationalised institutions and industries within 10 days of coming to power, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif decided to implement his new economic policy post-haste. Within a month-and-a-half of forming his government, the first privatisation took place: that of Muslim Commercial Bank, after which the privatisation process continued unimpeded. In 1992, under Nawaz Sharif, the Finance Act for passing the budget included the rule that if up to 75 per cent of goods were exported from a factory, labour laws would not apply — i.e. exports would be encouraged by the provision of concessions. Sharif also created special industrial zones in designated areas where even basic labour laws did not apply. And then as now, minimum wages were not applicable in agriculture. Thereafter, in 1992, some 120 big industries in the public sector were privatised and as a result, tens of thousands of workers became unemployed, and unions were wiped out.

In the army coup d’état of 1999, General Pervez Musharraf overthrew Nawaz Sharif’s government and implemented the PPP government’s US-IMF agenda more aggressively. During Musharraf’s nine years at the helm, some 350 institutions, big and small — bank, schools, industries, etc. — were privatised and about one million workers made redundant. This was, in fact, the biggest retrenchment in Pakistan’s labour history.

When the World Trade Organisation (WTO) came into being, it impacted Pakistan as well. It advocated outsourcing labour rather than hiring permanent employees so that employers would not have to fulfil obligations like covering healthcare costs, provident fund etc. Ninety per cent of the factory workers in Pakistan did not even have letters of appointment — and things have not changed since then. Next they decreed that organisations providing “essential services” to the armed forces could not have unions.

As a consequence, work began to shift from the formal to the informal sector. Interestingly, a person working in the informal sector, i.e. who works from his/her own home, is not recognised as a worker. Yet financial compulsions forced 20 million workers to join the informal sector. Only someone who works in the formal sector — in ‘work’ or office premises — works with a work standard, is entitled to go to the labour courts, receive a pension and receive social security. That notwithstanding, work started being delivered to workers’ homes, where entire families would work for a mere Rs. 1000/ — Rs. 1500 a month. And given that most workers in the informal sector are women, they are rendered particularly vulnerable.

Both Benazir Bhutto’s government and Nawaz Sharif’s were dependent on the IMF/WB, who made privatisation a basic conditionality for the disbursement of loans. That state of affairs continues till today. No one knows on what basis the transfer of a business, industry, or service from public to private ownership and control is being done, or what the criteria are for being awarded these factories. Some of the new proprietors even remain anonymous. And often, there is fabrication. In the case of the privatisation of the Pakistan Steel Mills for example, it was later discovered that the buyers Shaukat Aziz wanted to acquire Pakistan’s largest industrial complex, were not those that had been claimed.

Several state-run industries such as the PTCL, Sui Gas and Pakistan Steel Mills were delivering huge profits. During Musharraf’s government, major resistance to the privatisation of the Pakistan Steel Mills began, and a campaign was launched across the country to this end, compelling the Pakistani courts to take notice. The basic bid of the Pakistan Steel Mills — spread over 19,500 acres of prime land with an entire conveyor belt leading to the sea — was five billion rupees. The Shaukat Aziz government was selling that entire set-up for a mere 2.6 billion rupees. For once there was an uproar across the country, and one of the main reasons for the removal of Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry was his decision to halt the privatisation of Pakistan Steel Mills.

The then Chief Justice, Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry (over three non-consecutive terms (mid-2005 to December 2013) took a stand to try and save the remaining civilian institutions from being privatised.

A democratic civilian set-up was restored after Musharraf was forced to step down, and after the 2008 elections, the PPP formed its government under President Asif Ali Zardari. The very first ministry the new government created was for privatisation, and the minister chosen to head it was Naveed Qamar. Unfortunately for Sindh, from where the PPP won a landslide victory, the first target for privatisation was OGDCL’s largest operated gas-producing fields — the Qadirpur Gas Fields (near Ghotki, Sindh), where at least 10,000 of the workers were Sindhis. As this news went public, agitations erupted, with protestors demanding an end to privatisation. This state of affairs continued for nine days, with protestors surrounding Naveed Qamar’s house to prevent him from entering. The matter remains pending to date.

Zardari had wanted to give the industrialists the power of hire-and-fire over labour, as was the case during the Zia-ul-Haq period, when the captains of industry could hire and fire people at will. However, within the party were members like Raza Rabbani who allegedly strongly advised him against it, saying if they persisted, they would lose whatever support the party had left. But the manner of governance after Musharraf did not change. The PPP government set the minimum wage as Rs. 6000, but 90 per cent of the factories workers at that time did not even get this amount. And there was ongoing discrimination against women, which continues to the present day.

Near Karachi, is an export processing zone where there is rampant discrimination and sexual harassment against women, and where jobs are not given to married women. There is also said to be violence against women in the zone and the labour laws of the country are not required to be implemented there.

Obviously, Benazir Bhutto, Nawaz Sharif, General Pervez Musharraf and Asif Ali Zardari did not know — or care for this historical fact. Despite their outward differences, they have all had a uniform approach to labour policies, which has negatively impacted labour and their rights for the last several decades.

During the last four decades, the history of the labour movement has been of systematic fragmentation, the latest being along party lines, in which the the labour force in the country has considerably lost ground in its collective bargaining stance.

Unless the power relationship between the ordinary man and the industrialist/businessman changes, workers — the creators of wealth — will remain marginalised.

The Way It Was

Jinnah chatting with a group of members belonging to the Muslim Students Federation shortly after the creation of Pakistan in 1947.

Almost 100 years ago industrial unions or guilds were part of the fabric of the undivided colonised subcontinent. In fact there was one union for each industry or a sector or geographical area. The employees in the postal sector had one union (formed in 1922), which boasted a membership of more than 70,000. Unions had started forming prior to the Trade Union Act of 1926, which was pushed through by Muhammad Ali Jinnah. In fact, Muhammad Ali Jinnah also became the President of the All India Postal Staff Union in 1925. With the exception of uniformed personnel of the armed forces, this law ensured that everyone had the right to form an association of their own choice — even government employees. In fact, most unions that had been formed at that time were those of government employees, such as port workers, railway workers, postal workers etc.

In the Sindh province alone, there was a union of bidi-makers in existence even before Pakistan was created. The thellawallas had their own association. This law enacted by Jinnah was even broader than the ILO Convention on the Right of Association, which makes certain assumptions where the government can actually impose a law that does not allow them to unionise. The law allowed everybody to form a union, including the police.

The writer is working with the Newsline as Assistant Editor, she is a documentary filmmaker and activist.