Letter From India: Failed Healthcare and a Boost for Education

By Sujoy Dhar | News & Politics | Opinion | Viewpoint | Published 14 years ago

An Unhealthy Mess

An Unhealthy Mess

Like corruption, healthcare is a big shame for India, Asia’s third largest economy, which continually basks in its government-championed story of growth and success.

In the year 2000, while on a trip to the US for an Asian-American media conference in New York, I decided to check out a man from India, known for calling up India on landlines from the US, and talking endlessly about his particular case in several Kolkata courts. This man, an HIV/AIDS researcher from Ohio, lost his wife during a social visit to Kolkata in 1998, due to the alleged negligence of three of the city’s top doctors.

Since 1998, it’s been an incredibly long journey for Kunal Saha, as well as a journey of continuing shame for the Indian healthcare system.

I have known Saha via telephone conversations and emails since May 1999, especially since I was the Kolkata journalist reporting his case. But I first saw him in the US in September 2000, at the Greyhound bus depot in Columbus, Ohio.

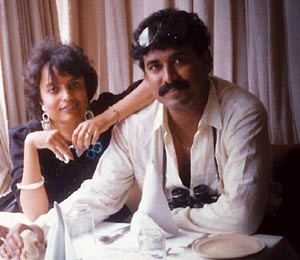

A six-foot tall, robust man in a navy blue suit and trademark dark glasses, he looked a bit intimidating. But behind the strong façade and stubborn spirit that waged a legal crusade against the medical system in India, I discovered a vulnerable man who had lost the love of his life — his wife, Anuradha, just 36 years old when she died. At his laboratory, I saw a proudly displayed picture of Anuradha, dressed in black and white. But that was only the beginning of confronting someone who inhabited Kunal’s world, more pervasive in death than when she was present in flesh and blood. At Kunal’s home, her presence could be felt everywhere.

In October this year, Kunal Saha made front-page news when he was awarded the highest-ever medical negligence damage in the history of Indian courts. He ran from pillar-to-post of every Indian court and consumer forum, and incurred heavy personal losses to fight the battle from far-away USA. While Anna Hazare’s movement has hogged all the limelight recently, Kunal Saha’s name probably does not ring a bell in New Delhi’s media like the many lesser fighters who bask in the spotlight on regular national channels. Saha has been a one-man army for nearly 13 years now; he set up India’s largest patients’ body to fight medical malaise, and many of his cases impact the moth-eaten frameworks of our institutions like the Medical Council of India (MCI), whose former president Ketan Desai was arrested last year for allegedly accepting a bribe of two crore rupees to grant recognition to a medical college in Punjab.

Saha was awarded the whopping amount of 1.7 crore rupees by the apex consumer court of India, the National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission (NCDRC). In view of his pyrrhic victory, Saha, though not happy with the amount, was pleased with the symbolic outcome of his long battle. It was not because Saha wanted the money for himself — he donated it to healthcare in India — his victory was an endorsement of his principled stand on the issue.

Saha alleged repeatedly that judicial corruption plagued his cases. This saga seemed like a war with many battles; some he won, some he lost. The delay in the delivery of justice for Kunal Saha has been so long, that even victories are not rejoiced. “Even though this is the highest compensation ever awarded in India against an errant doctor or hospital, the NCDRC judgment is a travesty of justice for more reasons than one. No matter how big 1.7 crore rupees may look in India, it is equivalent to just US$0.35 million in the US. I’ve already spent far more than this amount to fight my long-distance legal battle,” said Saha.

Saha also felt that the compensation earned would be equivalent to a couple of year’s salary for Anuradha, who was an Ivy League-trained child psychologist.

In the meantime, while the government healthcare system in India grovels, private hospitals can only fleece money under the guise of glammed up exteriors. The middle class, who are loathe to go to morbid government hospitals, suffer medical negligence and red herrings, and fritter away their savings accessing private healthcare.

The swanky exteriors of these hospitals continue to hide the sordid underbelly of medical corruption. Now, no one in India trusts a doctor, except maybe in south India, which attracts patients from the rest of the country and Bangladesh with the promise of better treatment. Due to government policies, doctors have become a despised community in the country. With the legal system and the governments protecting these errant doctors, it is often mob justice that pits the common people against the medical fraternity.

Saha’s significant judgement should not be lost on the money-minting private hospitals and negligent Indian doctors who have come to prioritise money-making as the sole aim of studying medicine. Saha’s compensation may be challenged again by the hospital and the doctors concerned in the Supreme Court, opening another delayed front between the Ohio man and India’s medical professionals.

Saha believes that the ‘bad apples’ in the Indian healthcare system must be identified and removed permanently. It is high time for the government to take a call.

Kapil Sibal, India’s minister for Human Resource Development and Telecoms, is seen as a legal eagle turned wily politician. He is a bugbear of the anti-corruption civil society group led by Anna Hazare. Sibal is one of the key lieutenants of the Union government arm-wrestling with the Anna group, in a tense battle of nerves. But this October, Sibal unveiled something new and exciting to cheer about — a computing device that may just narrow the digital divide in India.

Sibal launched Aakash, a low-cost-access-cum-computing device, which is being dubbed as the world’s lowest-priced tablet. This device, which will cost Rs 2,276 or nearly US$50, is developed by the UK-based company, DataWind, in partnership with the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Rajasthan.

Sibal, who believes Aakash will help eliminate digital illiteracy, has requested for additional technical support to make the device cheaper and, therefore, accessible to more people.

This current phase is a pilot to procure 100,000 devices. While production related issues are being sorted out, the device has been distributed to students across the country to extensively test various climatic and usage conditions.

According to a recent study, only a small portion of India’s 1.21 billion population has access to the Internet. If Aakash is made available to a majority of poor students in India, it can bridge the divide between a vast Indian population that remains distant from the digital revolution in the country.

This article first appeared in the November 2011 issue of Newsline under the headline “An Unhealthy Mess.