Bloody, Brilliant Diamond

By Deneb Sumbul | Published 8 years ago

The authors.

A brilliant gemstone is at the root of some of the subcontinent’s most fabled treacheries, tortures, murders, wars, conspiracies and fall of kingdoms in William Dalrymple’s riveting book — Kohinoor, the Story of the World’s Most Infamous Diamond. In true Dalrymple tradition, this 200-pager is a captivating historical narrative, meticulously researched and crafted with co-author Anita Anand. It gives a mesmerising account of more than four centuries of the legendary gem’s turbulent history. Sifting facts from its mythical origins and the mysteries that surround the Kohinoor, both historians wade through its foggy past and follow the brilliant orb’s fascinating trail as it changed hands between dynasties, kings, courtiers, invaders and treasury-keepers.

We are also introduced to the rudiments of gems and gemology and the various cultural preferences in jewels. It is fascinating to learn that, for centuries, diamonds only came from India and were not mined, but flowed down riverbeds. The authors give rich descriptions of the sheer wealth of brilliant stones and jewellery the Indian kings and temples possessed. The authors reveal that the Kohinoor had at least two rivals or lesser known sisters: the Darya-i-Noor (Sea of Light), now residing in Tehran, and the Great Mughal Diamond believed to be the Orlov diamond that adorns the Imperial Russian sceptre in Moscow. However, neither could hold a light to Kohinoor’s rich history.

The magnificent orb’s fame spread from South India to the courts of Maharajas in Northern India and it went on to become the crowning glory of the Mughal Court’s famed Peacock Throne. As indicated in the book, the earliest reference to it was made by Marvi, a historian of Emperor Shah Jahan’s court, who refers to it as ‘Koh-i-Noor’ — ‘Mountain of Light’ — in Persian. Shah Jahan was so bedazzled by the diamond’s magnificence that he had it set in his opulent peacock throne.

No other gem in the world has a comparable saga. The Kohinoor first left India more than 300 years ago with Persia’s most powerful ruler, Nader Shah (1736—1747), as war booty from Delhi, along with the Peacock Throne. There it resided for 110 years, after which it travelled to Afghanistan, where it remained for almost another 70 years, until the country disintegrated. The diamond returned to India in 1813 when Maharaja Ranjit Singh extracted it from Shah Shuja ul Mulk, the self-proclaimed King of Afghanistan, in 1801. The Kohinoor remained in Lahore — the capital of the Sikh kingdom — for another 36 years and became a powerful symbol of Sikh sovereignty. It was wrested away by the British colonisers once they gained complete control of India, who then shipped it to its final destination, London. There, it became part of the British Crown Jewels when Queen Victoria was proclaimed the Empress of India in 1877. The proverbial ‘jewel in the crown’ of the British Raj, has been caged in the Tower of London for over a hundred years now.

Some of the stories linked to the gem’s allure astound the reader, especially those in which certain potentates were driven to extremes to possess it, such as inflicting unbelievable brutalities, thereby extending the legend of the orb’s dark powers. Shahrokh Mirza (1748-1750), the grandson of Nader Shah, had molten lead poured onto his head by Qajar ruler, Agha Mohammad Shah — reminiscent of an episode from the American fantasy drama series, A Game of Thrones. Shah Zaman Durrani, the third King of Afghanistan (1770-1844), was blinded with hot needles. The ‘Kohinoor,’ inadvertently sealed the fates of its numerous masters and custodians, several of whom met grizzly ends in their single-minded pursuit to acquire it.

There is a fascinating anecdote about how, in order to prevent it from falling into the hands of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, it was hidden in the crack of a prison cell and later came into the possession of a Maulana who, in his ignorance, used the diamond as a paperweight. Perhaps the most poignant part of the diamond’s history pertains to the period when the British, through trickery and treachery, whisked away the Kohinoor forever.

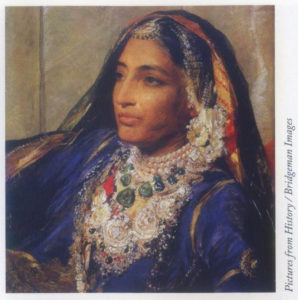

Of all the diamond’s masters, none coveted the Kohinoor more than Maharaja Ranjit Singh, ruler of the 19th century Sikh Empire. Despite having amassed one of the largest collections of prized gems — documented in great detail by the British after their conquest — the Kohinoor was only one of the few gems that Ranjit Singh wore, and with great pride. It came to symbolise the pride of Sikh sovereignty, for which a state-of-the-art security system had to be devised. Following the Maharaja’s death, the kingdom became embroiled in blood-soaked court conspiracies. The only royalty of significance who resisted British duplicity was Rani Jind Kaur, the 17th wife of Ranjit Singh and mother of the 10-year-old heir to the Sikh Empire, Duleep Singh.

The book details that, for the longest time, the fully militarised British East India Company — whose private army in 1800 was double the size of the British army — had an eye on Ranjit Singh’s cherished diamond and the powerful empire, the last free principality left in India that stood against the colonial rulers. The storytellers recall that the toughest battles fought by the British rulers and the East India Company against the valiant but ferocious Sikh armies were near the banks of the Sutlej River. And among the traitors, the most treacherous was Tej Singh, a powerful general in Duleep Singh’s army. He allowed his own forces to be defeated by the combined forces of the British and the East India Company in the First Anglo-Sikh War in 1845.

Both armies succeeded in infiltrating the Sikh Kingdom, and isolated the boy/king by forcibly separating him from his mother and having her imprisoned. Through connivance and deceit, the invaders compelled the minor King, Duleep Singh, to surrender whatever was left of his father’s legacy. Documented in Article III of the Treaty of Lahore, the Act of Submission reads, “The gem called Koh-i-Noor, which was taken from Shah Sooja ool-Moolk by Maharaja Runjeet Singh, shall be surrendered by the Maharaja of Lahore to the Queen of England.” The British conquerors recorded in detail the treasures and assets of the Sikh Toshakhana (treasury), which housed one of the largest collections of prized gems — a temptation after its annexation, that was too difficult to resist for some British soldiers who attempted to loot it by building a tunnel into one of the treasury rooms.

The lesser known British Governor General of that time, Lord Dalhousie, whose primary function in India was to appropriate its assets, took great pride in acquiring the diamond for his country. After receiving news of the prized diamond’s annexation, he wrote, “I have caught my hare…a sort of historical emblem of the conquest of India. It has now found its proper resting place.” But the diamond may have cast a shadow over his destiny as he did not garner the fame and glory he had hoped for.

Inexplicable incidents followed the diamond all the way to England. An extremely complicated plan, over land and sea, to deliver the diamond to the Queen of England, became a death-defying, nail-biting journey. The ship, Medea, that was secretly carrying the diamond in 1850, faced an outbreak of cholera. In danger of the entire crew being wiped out in the middle of the Indian Ocean, the ship dropped anchor near an island of Mauritius, which refused to allow it anywhere near the shore and even turned their cannons on the ship. Through negotiations, the captain convinced the islanders to provide them enough coal to power the ship and sail away. The ship next sailed into a 12-hour violent sea storm, with high winds and waves. Unnerved sailors prayed for deliverance and the three custodians of the Kohinoor became more convinced than ever that “the jewel was dragging them all to hell…”

Inexplicable incidents followed the diamond all the way to England. An extremely complicated plan, over land and sea, to deliver the diamond to the Queen of England, became a death-defying, nail-biting journey. The ship, Medea, that was secretly carrying the diamond in 1850, faced an outbreak of cholera. In danger of the entire crew being wiped out in the middle of the Indian Ocean, the ship dropped anchor near an island of Mauritius, which refused to allow it anywhere near the shore and even turned their cannons on the ship. Through negotiations, the captain convinced the islanders to provide them enough coal to power the ship and sail away. The ship next sailed into a 12-hour violent sea storm, with high winds and waves. Unnerved sailors prayed for deliverance and the three custodians of the Kohinoor became more convinced than ever that “the jewel was dragging them all to hell…”

The brilliant but accursed diamond seemed to have touched Queen Victoria as well. On July 2, 1850, the day the Kohinoor entered British territorial waters, the two-time former British Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, died of injuries sustained in a freak horse accident. The Queen, on the other hand, received the jewel the following day sporting a black eye — courtesy an ex-British army officer, who clubbed her with his cane without any reason.

Exhibited in the first of a series of World Fairs, the Great Exhibition of 1851 held in Hyde Park, London, the diamond did not live up to its hype. The exhibition’s chief organiser, Prince Albert, husband of the reigning British Queen Victoria, had the Kohinoor especially showcased as a prized exhibit in a specially designed Crystal Palace and it became one of the most popular attractions. And yet, for various reasons, it failed to dazzle the masses, who stood in long queues to see it. Prince Albert decided to have its lustre enhanced, which required giving it a cut that would halve its 190.3 carats and release its ‘fire.’ Although currently the Kohinoor is the 90th largest diamond in the world, its reputation remains unsurpassed.

to its hype. The exhibition’s chief organiser, Prince Albert, husband of the reigning British Queen Victoria, had the Kohinoor especially showcased as a prized exhibit in a specially designed Crystal Palace and it became one of the most popular attractions. And yet, for various reasons, it failed to dazzle the masses, who stood in long queues to see it. Prince Albert decided to have its lustre enhanced, which required giving it a cut that would halve its 190.3 carats and release its ‘fire.’ Although currently the Kohinoor is the 90th largest diamond in the world, its reputation remains unsurpassed.

Even today, as the gemstone firmly ornaments Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II’s crown, the superstition of misfortune lingers — it is believed that the Kohinoor will bring an untimely demise to any male potentate who wears it. The book hints that in the aftermath of the diamond’s violent chronicles, perhaps there may be good reason why no British male sovereign has worn it since its arrival in England. It was last seen on the coffin of the Queen Mother in 2002.

Much of the diamond’s history is linked with parts of the subcontinent, which now fall within Pakistan. It was not just the pride of the Punjab but of the Indian subcontinent, and in recent decades, five claimants — India, Pakistan, Iran, Afghanistan and even the Taliban in Afghanistan — have demanded the return of the gem at various times. For Pakistan, it was Zulfikar Ali Bhutto who first demanded the return of the gem. However, consecutive British governments have consistently maintained that the gem was obtained legally under the terms of the Treaty of Lahore.

Much of the diamond’s history is linked with parts of the subcontinent, which now fall within Pakistan. It was not just the pride of the Punjab but of the Indian subcontinent, and in recent decades, five claimants — India, Pakistan, Iran, Afghanistan and even the Taliban in Afghanistan — have demanded the return of the gem at various times. For Pakistan, it was Zulfikar Ali Bhutto who first demanded the return of the gem. However, consecutive British governments have consistently maintained that the gem was obtained legally under the terms of the Treaty of Lahore.

Nothing untoward has transpired since the cutting of the gem in half and since it left for England 167 years ago, where it has been residing in the Tower of London for over a hundred years now. Perhaps the cutting curtailed its curse.

The first half of the book written by Dalrymple, is culled from the mythical stories of the diamond’s history going as far back as the mid-1500s to the Vijayanagara state where India’s largest and richest deposits of diamonds were to be found. Anand’s narrative begins from the demise of the Sikh Empire. Both authors have written a gripping narrative. While clearly acknowledging the lack of records when none are available, the book encapsulates almost everything you need to know about the world’s most magnificent blood-soaked diamond — the Kohinoor.

The writer is working with the Newsline as Assistant Editor, she is a documentary filmmaker and activist.