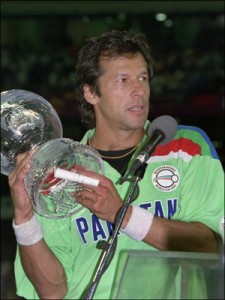

Imran Khan: A Life in Three Acts

By zain ali | News & Politics | Published 14 years ago

In public life, as author F. Scott Fitzgerald famously remarked, there are no second acts. Imran Khan has proven that aphorism to be utterly false. The man who was best known as a cricketing legend with a voracious appetite for both wickets and women, reinvented himself as a philanthropic do-gooder, setting up the first free cancer hospital in the country. These days, however, he is best known for his third, and possibly final, act in public life: that of a politician aligned with the religious right-wing.

In public life, as author F. Scott Fitzgerald famously remarked, there are no second acts. Imran Khan has proven that aphorism to be utterly false. The man who was best known as a cricketing legend with a voracious appetite for both wickets and women, reinvented himself as a philanthropic do-gooder, setting up the first free cancer hospital in the country. These days, however, he is best known for his third, and possibly final, act in public life: that of a politician aligned with the religious right-wing.

As jarring as each new avatar has been, Imran’s evolution (a word he would probably hate as he has made his opposition to Charles Darwin’s theory known) has been gradual and has even made some kind of sense.

If there has been one constant in Imran’s life it has been his thirst for competition. As a cricketer, he was notorious for never giving up. On his very first tour, as a raw youngster playing in England in 1971, he was told that he was lucky to have played even one Test match and there were murmurs that he had only made it to the team because of his more illustrious family members, like cousins Majid Khan and Javed Burki. Never one to give up, Imran trained harder, remodelled his bowling action and became the premier fast bowler of his time.

As his bowling prowess declined due to age and injury, Imran retooled himself as a reliable batsmen. Even more than his ability with bat and ball, though, it was Imran’s ability to lead that made him such a legendary cricketer. He united the notoriously fractious Pakistani cricket team through sheer force of will. He was a man who would not be denied his goals and became such a towering figure that even the head of state Zia-ul-Haq had to plead with him to come out of retirement and lead the team.

But if that had been the sum total of Imran’s exploits during his years as a cricketer, he would certainly have been remembered and loved in the same vein as other heroes like Hanif Mohammed and Javed Miandad, but would not have become the singular figure that he did.

It was Imran’s off-field reputation that added to his hero worship in Pakistan. As much as he would like to erase all memories of this part of his existence, Imran had been romantically linked to artist Emma Sergeant, Indian actress Zeenat Aman, fathered an out-of-wedlock child with Sita White and famously married heiress Jemima Goldsmith.

Imran was a regular presence at the nightclub Annabel’s and frequented parties at author Jeffrey Archer’s penthouse. At the 1996 Word Cup final in Lahore, among Imran’s guests numbered Rolling Stones’ singer Mick Jagger. Before he entered politics, Imran’s jetset, playboy lifestyle defined him as much as his cricketing exploits.

Imran was a regular presence at the nightclub Annabel’s and frequented parties at author Jeffrey Archer’s penthouse. At the 1996 Word Cup final in Lahore, among Imran’s guests numbered Rolling Stones’ singer Mick Jagger. Before he entered politics, Imran’s jetset, playboy lifestyle defined him as much as his cricketing exploits.

Imran didn’t move from playboy to fundo in an instant. Before that transformation was complete, there was the all-important second act.

For the last few years of his career, Imran was playing cricket for only one reason: to raise the money to build his cancer hospital in the memory of his mother, Shaukat Khanum, who lost her life to this dreaded disease. As with his cricketing career, Imran had to face off naysayers who told him that the task was a thankless and impossible one. Yet again, through sheer bloody-minded determination he was able to prove his critics wrong.

Another set of challenges faced Imran when he set up his political party, the Tehreek-e-Insaf, in 1996. Being successful in politics in Pakistan is close to impossible when you have no inbuilt support base. And political support in this country comes through land, wealth and patronage. Electoral success has so far eluded Imran, with his party putting up a dismal showing and failing to win a single seat in the 1996 elections and then only winning a couple of seats in 2003, and that too thanks only to seat adjustments with the Jamaat-e-Islami (JI).

It is Imran’s alliance with religious right-wing parties like the JI that has proved to be the most controversial move of his political career. His liberal supporters refuse to accept that the man who cavorted with multiple women could now align himself with such retrograde forces.

But even Imran’s seeming schizophrenia has some semblance of logic behind it. Even during his cricketing days, Imran adopted a fiercely anti-colonial attitude, loving nothing more than to bash the white countries for their supposed double standards. He always saw himself as the underdog, who constantly had to fight for the honour of his unfairly besmirched country.

He has taken that same attitude with politics. His alliance with the right-wing parties is based chiefly on anti-Americanism. His Pakhtun nationalism, which again was a part of his personality even while playing cricket, refuses to let him consider taking military action in FATA.

He has taken that same attitude with politics. His alliance with the right-wing parties is based chiefly on anti-Americanism. His Pakhtun nationalism, which again was a part of his personality even while playing cricket, refuses to let him consider taking military action in FATA.

Religion, too, has been a part of Imran’s life before he took up politics. He claims to have discovered and embraced Islam thanks to a spiritual friend who helped guide him in life. And there are limits to Imran’s supposed fundamentalism. He was one of the few politicians who had the courage to outright condemn the murder of Salmaan Taseer.

So far, Imran’s third act in public life is the only one where he hasn’t overcome the odds. But that too may be about to change. His party has been making inroads in the Punjab and there are signs that Imran’s appeal to the youth may translate into increased votes, making him a power-broker after the next elections. If there’s one thing we know about Imran Khan, it’s that he should never be counted out.

This article first appeared in the November 2011 issue of Newsline under the headline “A Life in Three Acts.”