Journey of a Thousand Miles

By Abdur Rauf Yousafzai | Newsbeat National | Published 6 years ago

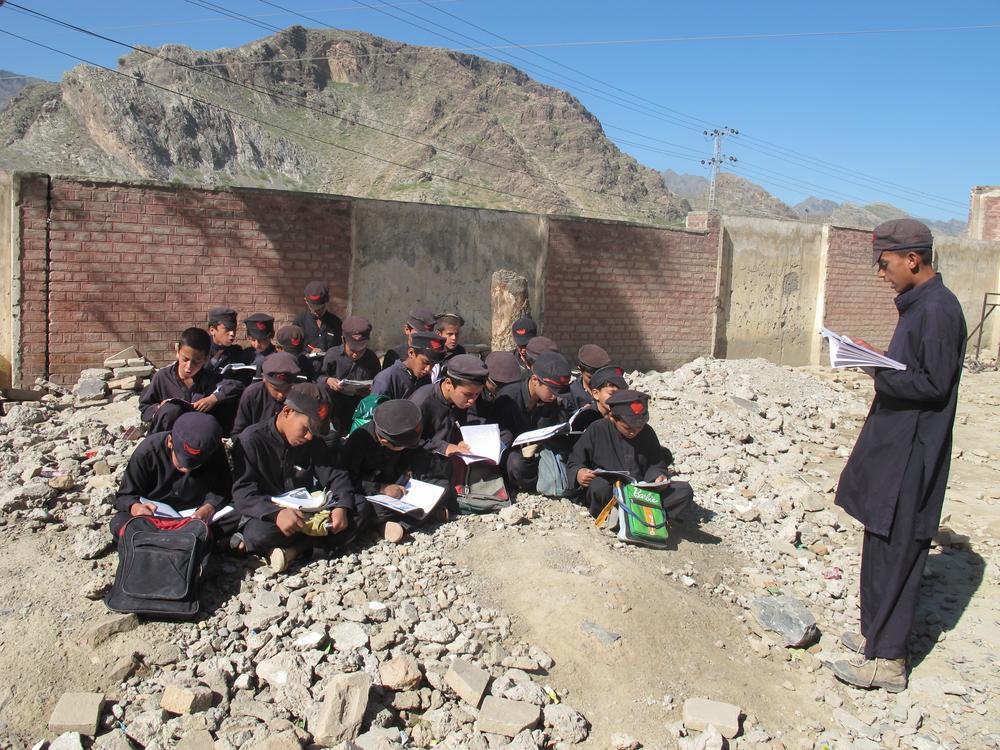

Primary school blown up in Mohmand Agency.

As far back as the 1940s, the first chief minister of NWFP, Khan Abdul Qayyum Khan, wrote in detail about the dilemmas faced by tribals in his book Gold and Guns on the Pathan Frontier. He talked of the need to increase the number of schools in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), and asked for scholarships to be earmarked for tribal children. In the history of Pakistan, Qayyum Khan may be considered an infamous politician, but his demands for the economic upliftment and widespread education for FATA in 1940 continue to resound even today.

In the long journey of seven decades since independence without a constitution, FATA has clearly made no progress. A case in point: FATA has never had a university till the present day.

In 1901, the British Raj introduced the Frontier Crimes Regulations (FCR) in a bid to keep the people of the area backward and eliminate the freedom fighters in the area. FATA’s residents still live under that draconian law, and rights accorded to other Pakistani citizens according to the constitution, do not extend to the tribals. The unfortunate truth is that extending the writ of the constitution to the tribal areas is not favoured by the civil and military establishment because of their misplaced belief in ‘strategic depth.’

In the ongoing war between the militants and the forces battling them, hundreds of educational institutions have been decimated by the former, who consider modern education westernised and a promoter of liberalism and vulgarity. It is not just education that has suffered.

The decade-long war has also played havoc with the region’s social, economic, and cultural setup, and it is perceived that this is part of an effort to destroy the centuries-old customs and code of life that has existed in the tribal belt bordering Afghanistan.

In 2001-02, the Directorate of Education FATA, established the Educational Management Information System (EMIS), to collect data on the education network in FATA. Deputy Director Planning & Development at the directorate, Zahid Wazir claims, “Since it started, the department has been publishing EMIS’s annual reports to provide accurate information regarding FATA’s educational infrastructure which enables planners and managers to take meaningful decisions to achieve better results.”

According to the 2015-16 EMIS report, 555 educational institutions in seven agencies and six Frontier Regions (FRs) were entirely destroyed during the war, and 491 were partially damaged. South Waziristan (SW), where 204 schools have been destroyed, has been hardest hit in this respect. In the Khyber Agency, the Mangal Bagh group, Lashkar-e-Islam, wrecked 180 institutions, while 116 institutions were razed to the ground in Kurram, and in the Orakzai Agency 159 schools have been damaged.

The Directorate of Education further confirms that 127 schools were blown-up in Mohmand, but reconstruction work is underway in 75 schools. In the Mohmand Agency, 70,000 students whose educational institutions were destroyed, are studying in alternate centres, including tent schools. Agency education officer, Khaista Rahman, contends that in April 2016, the Mohmand Agency sent a letter to the Directorate of Education, requesting books for 70,000 students. To date, he says, only books for 29,000 students have been received, while the remaining 41,000 students have been left waiting. Rahman adds that even the 29,000 students who did receive books did not get the required full sets.

Nosheen Jamal Orakzai is head of the Qabaili Khor (Tribal Sisters), a network struggling for women’s rights in FATA, which demands a share in the area’s political and social sectors. Nosheen hails from Orakzai Agency, where she was running a modern educational institution before fleeing to Peshawar after the militants overran her area. After capturing the area, they converted her school into a local court and an abattoir.

Jamal blames the Directorate of Education FATA for this state of affairs and demands compensation for all that has gone wrong. “For 60 years the central government, then the militants and military operations, and now the ‘white elephant’ that is the FATA Secretariat have been ruining the future of our children,” says Jamal.

Arshad Mohmand, a resident of the Mohmand Agency, narrates tales of the sentiments of local students’ parents. “They are worried that due to the negligence of the highly paid officials of the FATA Secretariat, their kids might miss another year of schooling.” Zahid Wazir, however, claims, “In the middle of routine admissions, the governor announced a massive enrolment drive,” which, he contends, really upset the ongoing school system, including the distribution of books.

Interestingly, the residents of North Waziristan don’t blame the militants for the destruction of educational institutions. Rasool Dawar, who works for Geo TV, hails from North Waziristan. He maintains that here the Taliban’s approach towards modern education was amazingly cooperative, that even when they controlled the area, the Girls Degree College of Waziristan was functional, with over 800 girls studying in it without any fear and no one was allowed to close or damage part of any educational institute.

Muhammad Shoaib, Deputy Director, Education, claims he remains optimistic about education in FATA. “The administration is trying hard to bring an uplift in the education system. In remote areas, where the schools have been fully or partially demolished, we have set up tent schools to begin with. We want the children back in school, and due to our recent enrolment drive, 126,000 students have been admitted to government schools, and 38,000 to private institutions.”

The director could not, however, provide any statistics about the number of out-of-school children. No survey was taken before the launch of the enrolment drive, which is now in its second phase, but officers at the Directorate of Education are expecting more than 100,000 to be admitted to the local schools.

Muhammad Shoaib adds that along with the tent schools they have set up, they are also working on repairing the damaged educational institutions in FATA to make them functional as soon as possible. According to Shoaib, during the militancy, 1195 educational institutions were partially or fully destroyed. The authorities are currently working on 892 schools, and hope to complete the reconstruction of the remaining 303 schools by the end of this year.

Muhammad Shoaib, who is responsible for book distribution in the tribal belt, however, offers his justification for the shortage of books. He reveals that annually, the Directorate of Education asks seven tribal agencies and six FRs for the book requirement in their areas. Their demands are then sent to the KP Textbooks Board.

This year, he says, thousands of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) were repatriated to their home towns, and “due to such a huge undertaking we faced logistical difficulties regarding the usual functioning of the education framework’s apparatus. But we have overcome this problem, and we have a system that will ensure that it all works out very soon.”

Bara, a subdivision of the Khyber Agency, is the native town of Lashkar-e-Islam chief, Mangal Bagh. When he gained control of the area, Bagh ran it according to his own interpretation of Islam. Due to his extreme hard stance on modern education, dozens of educational institutions were destroyed by his disciples. Today, 27 schools are still awaiting reconstruction in Bara.

Meantime, class four employees of the Government High School Alam Godar, are busy repairing tents in the Khyber Agency, ostensibly to provide cover for students in hot weather. But as one of those engaged in this task says, while sweating profusely, and under condition of anonymity, “These tents are the hottest place on earth. The children face immense difficulties while studying in them, while the education authorities live in airconditioned rooms.”

It is widely known that during the militants’ foray into this area, school attendance dipped dramatically in the Alam Godar High School. The statistics published by the FATA Education Directorate belie this. The 2007-8 enrolment numbers would, however, prove otherwise, but those are not accessible to the press.

School Principal, Janas Khan Afridi, is not reticent on this score. He maintains, “Before the war in 2009, our student strength was 1400. Now we have only 150 students studying here.” This drop owes to the takeover by the militants, their harsh stance on modern education, the mass destruction they wrought, and the fear this generated among students, their parents and the faculty, and the mass exodus all of this engendered.

Overall then, the current statistics for education in FATA and the FRs are abysmal. According to the EMIS 2015-16 report, the male-female ratio in this regard is 29.51 to 3.0 per cent. Collectively the figure stands at 17.42 per cent. Khyber Agency, adjacent to Peshawar, presents a better picture, with a high ratio of male students (39.86). Kurram Agency leads in female education.

Government tent schools.

Dr Ashraf Ali, the Executive Director of Zalan Communications, an organisation working in FATA, maintains that the statistics offered by the educational authorities of the area “are highly exaggerated.” According to him, between militancy and the military operations in the area, the resulting mass migration sizeably reduced the population, and consequently, school attendance.

Hayat Khan, a social activist and resident of Waziristan, migrated to Dera Ismail Khan after the military operation in his area. He is of the view that the authorities in FATA have focused on resuscitating only roadside schools to show donors, while the more far-flung areas, where the educational infrastructure was completely destroyed, are still waiting for the redressal of their problems.

He adds that government and non-government organisations alike claim to have conducted surveys of the affected areas, but “even though they have received billions of dollars in funding for remedial projects, they have done virtually no work on the ground.”

Now the authorities claim they are expecting 0.2 million in new enrolment in FATA schools. According to Muhammad Shoaib, the department wants to make this enrolment successful and has, therefore, involved the local administration, the security forces, the religious clergy, the media and other notables of the areas for help. “We are focusing on those areas (Khyber, Orakzai, Kurram, North and South Waziristan) where the people who had fled during the militancy, have returned to their native towns,” says Shoaib.

Aziza Mehsud is one of the rare female social activists in FATA, and the vice president of the FATA Students Federation. Born in South Waziristan and currently doing her MBA in Peshawar, Mehsud supports the military operations geared towards rooting out the militants, saying, “No doubt military operations were necessary, and we respect the sacrifices made by the forces for bringing peace back to the region.” But in the same breath, she criticises the poor planning for IDPs. “The war, then the inadequate rehabilitation of the locals afterwards and the slow reconstruction of the damaged properties have pushed FATA residents back into the dark ages,” she laments.

“The situation in FATA is dire,” says a local resident. “The socio-economic fabric of the area has been destroyed, thousands have died in the war — our brave soldiers and innocent bystanders who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time — leaving in the process so many widows and orphans. Those who witnessed the carnage have been left traumatised, and in dire need of psychiatric care.” To add insult to such catastrophic injury, the people of FATA are still living under the Frontier Crimes Regulations.

The recently declared FATA reforms package, with 120 billion rupees allocated for an overall uplift of the area, is a comprehensive plan for progress. But will it be implemented in letter and spirit? Dr. Ashraf Ali is convinced it will — and in the process, change the quality of life for the people.

Nosheen Jamal Orakzai also sees a ray of light in the migration of locals. “It was a blessing in disguise,” she says, “because it exposed the long-ignored, backwards and disenfranchised population of FATA to the cities and apprised them of their own rights.”

Perhaps that awareness, coupled with the funds promised for reform, will spell a new future for FATA. But that only time will tell.