Book Review: Painting The Persian Book of Kings Today

By Nilofur Farrukh | Arts & Culture | Books | Published 12 years ago

Epic Storytelling

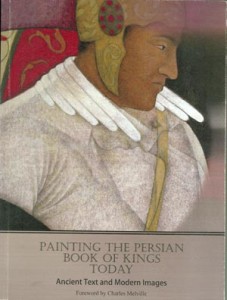

Painting The Persian Book of Kings Today: Ancient Text and Modern Images, an exhibition catalogue with its well-researched essays, gives access to different facets of Shahnameh Ferdowsi. It introduces the epic poem to the uninitiated reader and also helps artists, art scholars and art enthusiasts to trace the lineage of Mughal miniatures to the countless illustrations of Shahnameh Ferdowsi — the first of which appeared some 600 years ago. By creating linkages between historical narratives of imperialist expansionism and bloodletting, with present-day conflict in Afghanistan and Northern Pakistan, it highlights the politics of power, culture and religion.

The synthesis of contemporary visual interpretations of Shahnameh, with these sub-themes, has made the publication immensely readable and informative. Unfortunately the binding quality of the book can be a source of frustration for the reader as pages get detached from the spine as soon as you start leafing through it.

This publication is a part of the University of Cambridge’s Shahnama Project, initiated by Professor Charles Melville to celebrate the epic poem’s millennium in 2010. Artist, curator and educator Dr Fatima Zahra Hassan-Agha elaborates in the preface about how she was inspired “to curate a small but meaningful exhibition on the contemporary relevance of Ferdowsi’s epic poem, whose popularity seems only to have increased over the past 1,000 years since it was written.”

Charles Melville, in the foreward, provides the backdrop against which Ferdowsi undertook this commission. Painting the Persian Book of Kings Today traces the ancient history from the first known ruler of Ancient Persia, Gayomart, to the last ruler of the Persian Empire, Yasdegerd III, who died in AD 651, before the Empire was invaded and annexed by Muslim Arabs. Weaving through the reign of 50 kings, the narrative combines imperial history and myth, with the creative license of a poet, to create a powerful epic poem peopled by valiant heroes engaged in romance, betrayal and barbaric cruelty.

Melville asks if Shahnameh is “an Iranian phenomenon” or “a work of universal importance that still has fresh meaning for all of us today? And if so, how do the artists of today respond to its stories and messages?” In the four essays on the art of the publication, scholars and artists attempt to address these concerns.

Note: the variation in the spelling of Shahnama is due to the difference in the Persian and Urdu pronunciation of the word).

Note: the variation in the spelling of Shahnama is due to the difference in the Persian and Urdu pronunciation of the word).

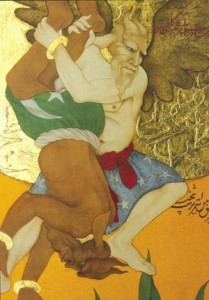

“Shahnama, the Other Story” by Suroosh Irfani, is an erudite account that uses Shahnama as a lens through which he examines 21st century ideological challenges. According to the author, “In the context of Afghanistan and Taliban insurgency in Pakistan, some of the Shahnama heroes like Rostom and Kay Khosrow assume a new meaning. As Rostom becomes the demon ‘Dev,’ inverting human values, and Kay Khosrow emerges as a post heroic figure, exemplifying generosity and justice for the whole world, the new readings are gestures for recovering an Indo-Persian culture, as a counter narrative, in the face of religious extremism — a counter narrative of an inclusive and pluralistic culture that may yet help to redeem Pakistan’s descent into chaos.”

A rather unexpected, but a welcome addition is Russian scholar Firuza Abdullaeva’s perspective on the women protagonists in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh. In “Ferdowsi: Male Chauvinist or Feminist,” she observes that often social standing rather than gender determines the treatment meted out to the leading women in the epic poem and is disappointed when these characters are discarded abruptly while heroes are allowed to evolve with the central plot. Her study gives an insight into Ferdowsi’s perception of societal attitude towards women throughout history.

The sumptuous reproductions of paintings grouped in three sections called Amal 1, 2 and 3, illustrate the lasting influence of Shahnameh as an iconic work which has compelled masters for centuries, to create replications and variations of the epic poem. In its 21st century adaptation, the characters and legends of Shahnameh transform into metaphors of a new age.

The texts leave little doubt that in the last 10 centuries the poem has stirred the creativity of artists and writers, and through the tradition of oral recitals, entered the imagination of the common man.

The catalogue establishes the paradigmatic shift in the adaptation of Shahnameh in contemporary visual arts, that has been made possible by the revival of miniature painting which offers a formal indigenous cultural framework for artists to work with. The discourse emerging from this is worth exploring not only as an academic exercise, but as a tool to understand the overlay of multiple cultural identities in the region.

The research essays in Painting the Persian Book of Kings Today: Ancient Text and Modern Images effectively revitalise history with a critical discourse. The catalogue should be made a part of the reading list in all art schools, particularly miniature painting departments in Pakistan and abroad.

This book review originally appeared in the November 2011 issue of Newsline under the headline “Epic Storytelling.”

The writer is an art critic and curator. Her work covers art criticism, art history, curatorial projects, art education and art activism. She has been regularly contributing to national and international journals since 80’s.