Unveiling Islam

By Ayaz Amir | News & Politics | Published 9 years ago

They gathered in the tens of thousands for the funeral of Mumtaz Qadri — Salmaan Taseer’s bodyguard turned blasphemy-inspired killer — and people who take fright at such things were alarmed, and doleful commentaries came to be written, the pulsating crowds at the event taken as a reflection of Pakistani society.

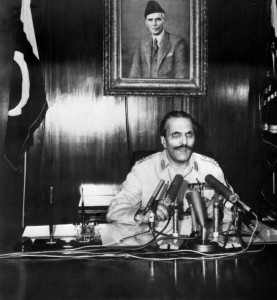

But many people tend toforget that there was a huge,virtually unprecedented turnout at the funeral of Gen. Zia-ul-Haq. Islamabad had seen nothing of the kind. Faces streaming with tears could be seen all around and from powerful loudspeakers poured forth ceaseless tributes, singing the praises of the departed and lamenting that the world of Islam had lost one of its most valiant sons. Azhar Lodhi, a television fixture of that era, was one of the eulogists at the mike as was that hero of many a changing moment, Hussain Haqqani. For many years anniversaries of the general’s death were also full-blown affairs, thousands in attendance including someone not above calling himself heir to the general’s legacy, one Muhammad Nawaz Sharif.

And then the crowds started thinning at that annual event and the time even came when Nawaz Sharif no longer felt it necessary to put in an appearance. New realities had arisen and Nawaz Sharif was now his own man, and the general’s long period at the helm was becoming a distant memory. Today who remembers that anniversary?

So a precedent is there. The Barelvi denomination to which Mumtaz Qadri belonged will continue making much of his ‘martyrdom’ and his grave outside Islamabad will in all probability acquire the semblance of a shrine where Barelvis come to make their offerings. But Qadri’s death becoming a rallying cry for the devout and the faithful? These things come and go. The seasons pass and passions subside.

Whatever meaning one reads into the large congregation at Qadri’s funeral, more significant was the fact that the Pakistani state—the post-Zarb-e-Azb Pakistan—felt confident enough to carry out the hanging. Not only that. It also felt confident enough to allow the funeral to take place at Liaquat Bagh in downtown Rawalpindi.

Whatever meaning one reads into the large congregation at Qadri’s funeral, more significant was the fact that the Pakistani state—the post-Zarb-e-Azb Pakistan—felt confident enough to carry out the hanging. Not only that. It also felt confident enough to allow the funeral to take place at Liaquat Bagh in downtown Rawalpindi.

There were riots in a few places and then there was calm. There were some disturbances on the occasion of Qadri’s chehlum, the 40th day of mourning, even a dharna at the famed D-Chowk in Islamabad, with members of the bearded brigade vandalising public property, committing acts of arson and threatening to enter parliament if their charter of demands was not met, but these disturbances were of a sporadic sort, and until last count, at least, the frenzy wherever it had arisen, was over.

Pakistan is a conservative society where Islam plays a heavy part in the lives of most people. But Pakistan was not born an extremist society. It was turned into one — and this circumstance should be noted and engraved in stone — not by the mullah or the firebrand preacher spouting fire and brimstone from the pulpit but by the English-speaking ruling class, whether dominating politics or commanding the army.

In Pakistani political lore, the Objectives Resolution, which gives a religious colouring to the creation of Pakistan, is taken as a point of departure—the seminal moment when the vision of a tolerant society envisioned in Jinnah’s address to the Constituent Assembly just a few days before Pakistan’s appearance on the map gave way to a more religion-loaded interpretation. But no one forced the Constituent Assembly to adopt that resolution. Some forceful clerics were its advocates but outnumbering them were ‘liberals’ like Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan and Foreign Minister Sir Muhammad Zafarullah Khan.

Not the least of the ironies on display on that occasion lay in the circumstance that the most powerful speech, brimming with eloquence, in support of the resolution was delivered by Sir Muhammad Zafarullah Khan… whose Ahmadi sect many years later found itself ostracised from the pale of Islam during the rule of another ‘liberal,’ Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who should have been the last person to mix religion with politics but who, to his eventual mortification, did…what is more, receiving no thanks for this endeavour.

Another ‘liberal,’ a product of Christ Church Oxford, Mian Mumtaz Muhammad Khan Daultana, as chief minister of Punjab tried to exploit the anti-Ahmadi riots of 1953 as a tool against the central government headed by Prime Minister Khawaja Nazimuddin. He gained nothing from his surreptitious politics, but another milestone on the road to intolerance was laid.

Another ‘liberal,’ a product of Christ Church Oxford, Mian Mumtaz Muhammad Khan Daultana, as chief minister of Punjab tried to exploit the anti-Ahmadi riots of 1953 as a tool against the central government headed by Prime Minister Khawaja Nazimuddin. He gained nothing from his surreptitious politics, but another milestone on the road to intolerance was laid.

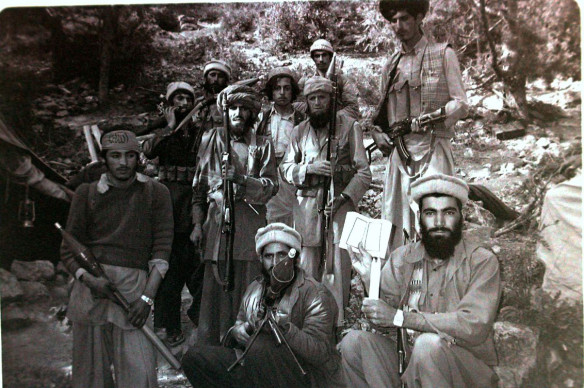

The real turn of the screw, however, came with the first Afghan ‘jihad,’ 1978-89, when Islam became the battle cry against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. Even if the aim was laudable — fighting the Soviet occupation — the heedless methods employed laid the groundwork for the rise of extremist Islam and for turning Pakistan into the world’s epicentre of ‘jihad.’

Al Qaeda was the first offspring, Daesh or the Islamic State coming much later. But the genealogical tree goes back to the Afghan ‘jihad,’ the original Garden of Eden.

Mullahs and religious parties were the foot soldiers in that enterprise. But the policy itself came not from any mosque or pulpit but from the English-speaking environs of the army high command. The language of the Pakistan Military Academy is English. That of the Army Staff College and the National Defence University is English. And products of these institutions were in the forefront of promoting the politics of ‘jihad.’

The mullahs and the products of Islamic madrassahs, by then liberally funded by Saudi money, gyrated to the master tunes emanating from those powerful sources…which in turn were cosseted and supported by such other centres of ‘liberalism’ as the Central Intelligence Agency. So it bears repeating that the illuminati of Islamic centres of learning were the fodder of that war. The higher inspiration came from elsewhere.

It is not just Pakistan which has paid an ample price for secular-inspired religious follies. Europe and the United States are also paying a heavy price.

Pakistan’s turn to religiosity under General Zia was not a phenomenon led by the mosque. It came from the army and because that original impulse came from that powerful source, its effect was deadly and long lasting. It pushed Pakistan to the right, made a conservative society more conservative, injected religious discourse into the national framework and smoothed the path for the Pakistan Muslim League-N’s rise to power. Nawaz Sharif may have other things going for him but in the last analysis he remains the most enduring product of the military-led political engineering of the Zia era.

The terrible blast on Easter in Lahore’s Gulshan-e-Iqbal Park and other stray incidents of terrorism notwithstanding, Pakistan is now turning a corner not because of any political awakening or popular upheaval but because the army, in a spirit of enlightened self-interest, has thought it best to change course. The espousal of ‘jihad,’ far from serving the army’s interests as once thought it did, is now seen as a danger to the state, it having been conclusively established that Frankenstein had turned on his creator.

Some conclusions are thus easily drawn. Pakistan became a laboratory of extremist thought not because the mullahs had become powerful but because the army and its school of advanced ideology, the ISI, in pursuit of their own hazy ideas, decided to wear the mantle of the mullah. The mosque did not conquer the state, much less the army. The army co-opted the mosque and the mullah and lived to rue the outcome.

Pakistan is thus not at the mercy of the religious firebrand. The inspired doctor of the faith can never rise to the eminence where he becomes a threat to the state. It is the state and its most powerful instrument, the army, which imperil Jinnah’s Pakistan when for purposes only dimly understood they ape the mullah and adopt his language.

Pakistan is thus not at the mercy of the religious firebrand. The inspired doctor of the faith can never rise to the eminence where he becomes a threat to the state. It is the state and its most powerful instrument, the army, which imperil Jinnah’s Pakistan when for purposes only dimly understood they ape the mullah and adopt his language.

People and polity are powerless. The political class is clueless. In the Zia-led army lay Pakistan’s greatest danger. In a transformed army command rests Pakistan’s hope for the future. One can only hope the army does not get it wrong again.

This article was originally published in Newsline’s April 2016 issue.