Book Review: Sadequain

By Nusrat Khawaja | Books | Published 9 years ago

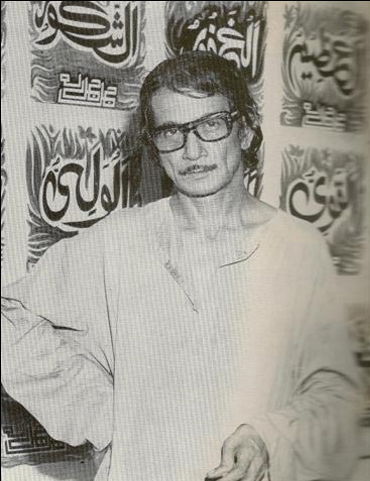

Sadequain is arguably Pakistan’s most iconic artist. His oeuvre included figurative and calligraphic work in a variety of media as well as illustrations of his own verse. He was known for gifting his paintings to friends and patrons in exchange for the beverage that supplemented his irrepressible energy to create expansively. His emaciated frame belied his prodigious output. The art market in Pakistan during Sadequain’s lifetime was less investment-driven than it is today and his attitude towards his own work was the antithesis of commercialism. Today, Pakistani art has arrived on the scene of the international art market and Sadequain’s value has skyrocketed. His painting titled ‘Imagination’ sold at Bonham’s for 60,000 UK pounds just two years ago.

Sadequain is arguably Pakistan’s most iconic artist. His oeuvre included figurative and calligraphic work in a variety of media as well as illustrations of his own verse. He was known for gifting his paintings to friends and patrons in exchange for the beverage that supplemented his irrepressible energy to create expansively. His emaciated frame belied his prodigious output. The art market in Pakistan during Sadequain’s lifetime was less investment-driven than it is today and his attitude towards his own work was the antithesis of commercialism. Today, Pakistani art has arrived on the scene of the international art market and Sadequain’s value has skyrocketed. His painting titled ‘Imagination’ sold at Bonham’s for 60,000 UK pounds just two years ago.

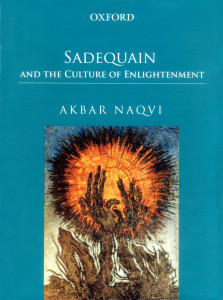

Despite his renown, Sadequain remains an enigmatic persona and there is a huge deficit of scholarly work on him. Akbar Naqvi has contributed towards a remedy of this deficit in his book Sadequain and the Culture of Enlightenment. Printed on high quality matte finish paper, the book is a handsome artefact, brought out by Oxford University Press, Karachi. The font and type nicely show up the Urdu verses included in the English text, and the images have come through with good colour fidelity.

Within the book, a set of eight digressive essays provides a commentary on Naqvi’s dual preoccupation with Sadequain and the subcontinental enlightenment tradition within which he belabours to contextualise the artist. These two discussions interweave periodically but often remain separate. In particular, the later chapters on some émigré artists who exemplify the heterogeneous strands in Pakistani art and the chapter on al-Beruni and Amir Khusro, read as stand-alone essays with tangential reference to Sadequain.

With respect to plastic arts in Pakistan, it fell to these émigré artists, who had moved to the newly created state, to bring with them the tradition of Indian syncretism. Naqvi devotes a chapter each to Chughtai, Shakir Ali and Shahid Sajjad as major contributors of syncretic style to Pakistani art. Chughtai brought an Indo-Persian flavour to the mélange, Shakir Ali connected with Cubism and Shahid Sajjad explored Primitivism through sculpture.

The cultural context for regional enlightenment, as elaborated upon by Naqvi, appears to be rooted in what Marshall Hodgson has termed “Islamicate” traditions which: “would refer not directly to the religion, Islam, itself, but to the social and cultural complex historically associated with Islam and the Muslims, both among Muslims themselves and even when found among non-Muslims.”

Naqvi links the impetus for enlightened modes of behavior to the doctrine of sulh-e-kul or peaceful co-existence as promulgated  by Jalaluddin Akbar. Multiculturalism versus orthodoxy has remained an age-old conflict in Muslim societies, and Naqvi clearly attributes the flourishing of culture and tradition to heterodox thinking as exemplified by Sir Syed Ahmed Khan’s reformist exhortations, Ghalib and Iqbal’s poetry and Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s socially conscious poetic expression. This broad context provides the framework within which Naqvi identifies the genesis of Sadequain’s idiom.

by Jalaluddin Akbar. Multiculturalism versus orthodoxy has remained an age-old conflict in Muslim societies, and Naqvi clearly attributes the flourishing of culture and tradition to heterodox thinking as exemplified by Sir Syed Ahmed Khan’s reformist exhortations, Ghalib and Iqbal’s poetry and Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s socially conscious poetic expression. This broad context provides the framework within which Naqvi identifies the genesis of Sadequain’s idiom.

Among the syncretistic influences on Sadequain, Naqvi elaborates at length on the critical importance of the Malamati philosophical tradition which originated in 9th century Nishapur. The idea of self-blame, self-criticism and the shunning of exaggerated piety as an ostentatious affectation, was essential to the practices of this school of mysticism. Malamati discourse attempted to find a spiritual path by a psychological interpretation of behaviour. It may be said that this deeply humanist school of mysticism bore within it the essentials of angst and with respect to angst, one can see a clear link to Sadequain. Naqvi says Sadequain “laid bare his wounds of odium, which entrance us and bring about catharsis.”

Sadequain’s anguished portrayal of humanity in the image of the headless man (sar-ba-kaf) carrying his decapitated head in his hand is a recurring one in his paintings. Naqvi convincingly speaks of this image as a link to the Malamati aesthetic and explains: “Sadequain was not a Sufi but the product of the Malamati tradition of his culture and tradition, which emphasised ikhlas.” An important distinction is made in this argument that absolves Sadequain from being a “holy sinner” to being an existentialist who takes responsibility for his own flawed state.

Naqvi has attempted a grand unification theory of multiple influences that bear on Sadequain’s life-style and art. His recall of historical elements is peppered with his own encounters with the polite but stubborn artist. The book is not a conclusive study of Sadequain but it is an important contribution in reigniting a discussion on a national icon.

This review was originally published in Newsline’s April 2016 issue.