Art Review: Muhammad Ali

By Nusrat Khawaja | Art Line | Published 9 years ago

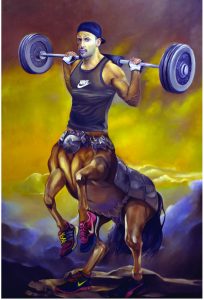

The walls of Canvas Gallery glow with the modulated luminosity of nine large oil-on-canvas paintings. In his show titled ‘Emperor’s Real Clothes’, Muhammad Ali has created seductive montages — fantasies that articulate the hedonism of the age of plenty by depicting monumental and beautiful portraits.

Unlike the emperor in the Hans Christian Andersen fable, who actually parades naked in a parody of self-importance, Muhammad Ali’s characters are richly attired in realistically painted cloth. The fabric flows and drapes over their forms like a stream with many rivulets.

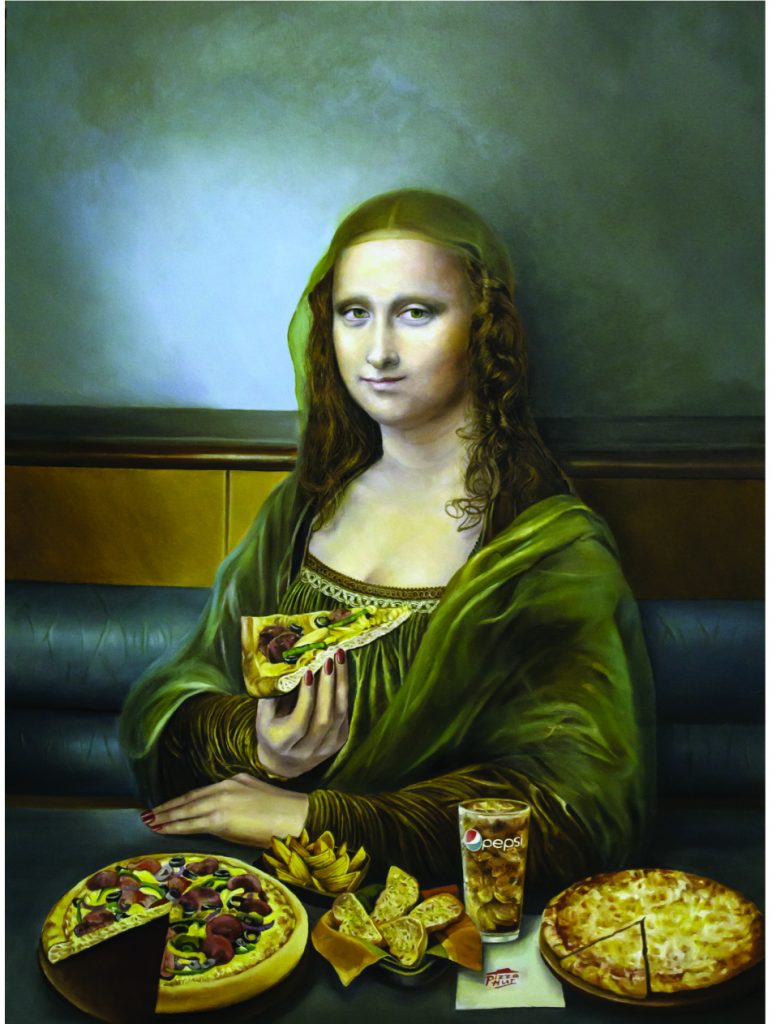

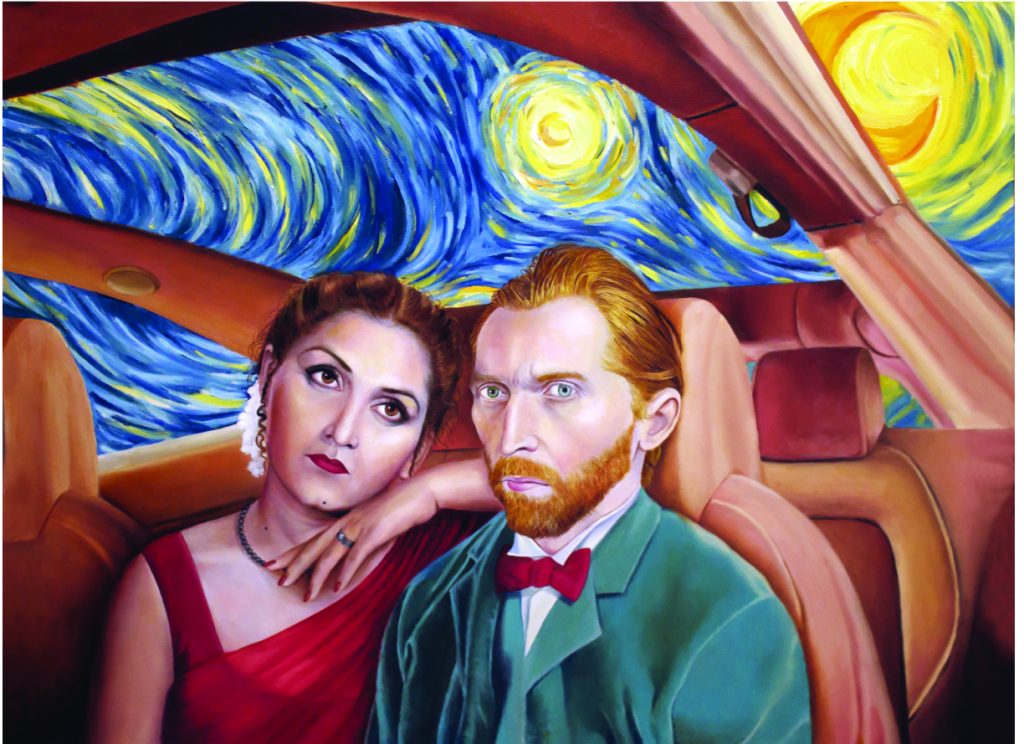

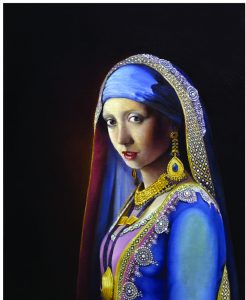

There is Leonardo’s ‘Mona Lisa’ in her dark silken drapes with gold trim at the neck. Vermeer’s ‘Girl with a Pearl Earring’ dons Pakistani wedding couture and jewellery. A youthful Madam Noor Jehan enchants in a crimson chiffon sari which sets off her companion, van Gogh’s red bow tie. And there are three paintings of the Madonna draped in her voluminous shawl which is golden green instead of the traditional blue.

The attention to costume is important because it contributes to the sense of theatricality that these beautifully painted canvases convey. They are akin to stage stills with the characters poised in a tableau vivant of sorts. And what characters!

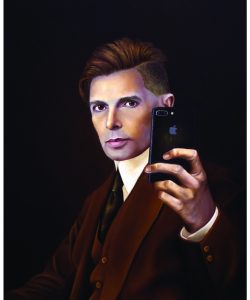

The viewer is drawn into a fantasy world in which a dapper Mr. Jinnah with a pompadour haircut holds an iPhone and the Mona Lisa contemplates gorging on pizza. The paintings deliver multiple messages with playful visual puns as a comment on the consumerism of our age. The messages are not difficult to decipher and that is what the artist intends. He states: “My paintings are intended to be accessible and easily understandable using the visual acumen that is common to all participants.”

The viewer is drawn into a fantasy world in which a dapper Mr. Jinnah with a pompadour haircut holds an iPhone and the Mona Lisa contemplates gorging on pizza. The paintings deliver multiple messages with playful visual puns as a comment on the consumerism of our age. The messages are not difficult to decipher and that is what the artist intends. He states: “My paintings are intended to be accessible and easily understandable using the visual acumen that is common to all participants.”

Muhammad Ali is a bold and unapologetic appropriator of iconic characters from well-known works of art. These characters are recontextualised in time and space. The outcome is a disjunction that provides a narrative that is radically different from the one they are traditionally associated with.

Muhammad Ali is a bold and unapologetic appropriator of iconic characters from well-known works of art. These characters are recontextualised in time and space. The outcome is a disjunction that provides a narrative that is radically different from the one they are traditionally associated with.

One of the three paintings depicting the Madonna is titled ‘Oops! Did i buy Champagne instead of Milk again?’ Muhammad Ali has appropriated the serene form of the standing Madonna from William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s (d.1905) painting called ‘Innocence.’ The original painting shows the Virgin holding a sleeping infant Jesus in her right arm. A lamb is held in her left arm and it is a symbol of innocence. The background of the painting is pastoral.

Muhammad Ali recasts this image in the context of a suburban supermarket parking lot. There is a trolley full of groceries waiting to be loaded into a hatchback car. The lamb in the Madonna’s arm has been replaced by a packet of Pampers. Mary, the quintessential icon of motherhood, is performing a quotidian task that millions of housewives carry out. She is dutiful and yet the title of the painting suggests that she is not quite the ultimate goody-goody. Muhammad Ali has deconsecrated the iconic Madonna by bringing her image out of the sublime realm into the ordinary one. Her image nonetheless — by virtue of being appropriated — retains some of its original connotations. The ordinary therefore becomes “contaminated’ with what has henceforth been entirely sublime. The incongruity between image and context creates a dialectical dynamic of thought associations between the sublime and the mundane.

Muhammad Ali recasts this image in the context of a suburban supermarket parking lot. There is a trolley full of groceries waiting to be loaded into a hatchback car. The lamb in the Madonna’s arm has been replaced by a packet of Pampers. Mary, the quintessential icon of motherhood, is performing a quotidian task that millions of housewives carry out. She is dutiful and yet the title of the painting suggests that she is not quite the ultimate goody-goody. Muhammad Ali has deconsecrated the iconic Madonna by bringing her image out of the sublime realm into the ordinary one. Her image nonetheless — by virtue of being appropriated — retains some of its original connotations. The ordinary therefore becomes “contaminated’ with what has henceforth been entirely sublime. The incongruity between image and context creates a dialectical dynamic of thought associations between the sublime and the mundane.

Even more bizarre is the dialectic created in the lengthily titled painting: ‘Achi si ek gari ho, Larki usmein pyaari ho, Aur ek night starry starry ho.’ Madam Noor Jehan snuggles up to Vincent van Gogh who looks like an airbrushed version of his ‘Self Portrait’ circa 1889. They are seated in a motor car. The night sky is visible through the rear windshield and it resembles the celestial swirls of van Gogh’s ‘The Starry Night!’ Madam has a dreamy faraway expression. Perhaps she is reminiscing about ‘Chandni Raatein’ which she sang for the film Dupatta in 1952 in which she herself was a star.

Even more bizarre is the dialectic created in the lengthily titled painting: ‘Achi si ek gari ho, Larki usmein pyaari ho, Aur ek night starry starry ho.’ Madam Noor Jehan snuggles up to Vincent van Gogh who looks like an airbrushed version of his ‘Self Portrait’ circa 1889. They are seated in a motor car. The night sky is visible through the rear windshield and it resembles the celestial swirls of van Gogh’s ‘The Starry Night!’ Madam has a dreamy faraway expression. Perhaps she is reminiscing about ‘Chandni Raatein’ which she sang for the film Dupatta in 1952 in which she herself was a star.

Muhammad Ali’s figurative works imaginatively combine familiar and unfamiliar elements into allegorical renditions. Myth-making is alive and well in the age that extols the celebrity cult and this, after all, is what the ‘Emperor’s Real Clothes’ is about.