Partition’s Little Red Book

By Raza Naeem | Bookmark | Published 8 years ago

The fire of civil war is raging in India and Pakistan; its flames threaten to burn humans, houses and libraries, along with our life, freedom, culture and civilisation, to ashes. Today, after many months, these flames have lessened, but have not gone cold yet… But there is no scarcity too of firefighters. The healthy and progressive elements of India and Pakistan are trying to stop this civil war and it can be said with certainty that they are the ones who will be victorious. Because time, history and the future, are with them. The demands of life are strengthening them.”

These words were not written in the current times of demagogic populism and right-wing fundamentalism in the two largest states of the Indian subcontinent, but amid the chaos and confusion of the partition of India, 70 years ago, when the prominent progressive poet, Ali Sardar Jafri, and many of his comrades on both sides of the divide were thinking about how best to combat the calamity that had just taken place.

Jafri was writing these words as a preface to a searing collection of Partition stories by his comrade Krishan Chander, titled ‘Hum Wehshi Hain’ (We Are Savages), which were released within a year of the horrific events of 1947. Jafri had noted in his preface that Chander was among a handful of writers who refused to be silenced by the sheer violence and brutality of Partition. Others included Upendar Nath Ashk, Ismat Chughtai, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, Kaifi Azmi, Yusuf Zafar and Fikr Taunsvi. However, Jafri had curiously omitted a notable — or notorious — literary intervention in partition literature, released in the same year as Hum Wehshi Hain. This was the equally biting Siyah Hashiay (Black Margins) by Saadat Hasan Manto.

The year 1948 thus saw two notable literary interventions on the partition of India, from Chander and Manto. Both works received excoriating reviews from either side of the ideological divide. Manto’s intervention was criticised by Jafri, the doyen of progressive writers at that time. Muhammad Hasan Askari, a noted Pakistani literary critic, not only wrote the preface to Siyah Hashiay, he also made a veiled attempt to attack Chander’s contribution in the same preface, in the following words: “If in the beginning (of the short story), five Hindus had been killed, then by the end of it, the calculation of five Muslims should balance it.”

Likewise, Chander’s intervention was supported by his progressive comrades like Chughtai and Abbas, but roundly criticised by Askari and other critics like Mumtaz Shirin and Anwar Sadeed. It is Chander’s volume that I will focus on, for two reasons. Firstly, because it is, surprisingly, not very well known among the voluminous oeuvre of Chander. I have written elsewhere that though Chander wrote almost 5,000 short stories — by far the largest number among his peers — most of his critics, editors and translators have seldom bothered to read his work post-1947, quietly distancing themselves from what they perceived to be his ‘romantic’ or socialist realist style.The second reason I am interested in Chander’s volume is because it is often dismissed by even the most discerning literary critics.

Hum Wehshi Hain consists of seven stories depicting memorable characters drawn from a wide cross-section of society in colonial India. There are middle-class, nominally religious Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, motivated by the hysteria and revenge — the seeds of which were sowed by their leaders; there are Maratha goons parading about in colonial Bombay, peanut-sellers and prostitutes; racist Anglo-Indian administrative toadies in the twilight of their careers; wine-drinking maulanas; martyrs of Jallianwala Bagh; Muhajireen and ‘Sharnarthis;’ veteran Ghadarites and Congressmen; a young girl reading up on philosophy and socialist praxis.

What is it that is controversial about these stories?

They try to understand the brutal tragedy which happened in the wake of Partition, from the points of view of various characters across class, gender and ideological divides. While five of the stories are more conventional, there are two — ‘A Courtesan’s Letter’ and ‘Peshawar Express’ — that stand out as unusual.

‘Blinded,’ is a satire on Muslim prejudices about Hindus on the eve of Partition and is set in a predominantly Muslim mohalla, where two Hindu households stand out conspicuously. The narrator, himself a victim of such prejudice, is in love with a young woman from one of the Hindu households. Amid the frenzy of Partition, the narrator is shown to be part of a group of Muslim ruffians who ransack the two Hindu homes in their locality. As the wanton arson and murder ensues, they come upon an infant lying peacefully in his cot. Although murderous instincts prevail, the child is saved when the narrator remembers his own child at home. However, in a masterful twist of irony, upon reaching his own home with the loot, he finds his whole family — including his child — slaughtered by Hindu goons. Blinded by his loss, the narrator resolves to seek revenge. Thus, a miniscule moment of humanity for the other is enveloped by a murderous communal passion.

In ‘Lal Bagh’ (Red Garden) Chander masterfully depicts the story’s main character, Kamlakar, a criminal gangster referred to as “dada.” In Chander’s words, “It is easier to become the governor-general of India and Pakistan, but to become the dada of Lal Bagh is not easy.” The Partition riots come as a huge opportunity for his opium, hashish and cocaine racket. Though profit and capital do not distinguish between Hindu and Muslim, here Kamlakar encourages his henchmen to maintain order by killing Muslims, while protecting the interests of poor Hindus. We are shown a scene where one of Kamlakar’s henchmen takes his boss to show him the murderous pickings of the day and Kamlakar filches a bottle of oil still clenched in the fist of a murdered youth, giving it to his deputy saying, “Well done, take this bottle of oil, it will help some poor Hindu.” Then, from Kamlakar and his heinous patronage networks, the focus shifts to the poor victims, all of them Muslims, one of whom is poor Sheedu, a peanut seller from Bareilly who had sworn to remain in Lal Bagh, expecting no retribution from his “brother Hindus,” but who eventually pays the price because “he was the only one [Muslim] left and I [the murderer] needed the fifty rupees.”

‘A Courtesan’s Letter Addressed to Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and Quaid-e-Azam Jinnah’ is, in my opinion, the most striking story in the volume, and not the more frequently anthologised and discussed ‘Peshawar Express.’ One attraction is created by the very simple title of the story, the second being the assumption of unequal power inherent when a ‘courtesan’ dares to address the two eminent nationalist leaders of divided India — the two leaders partly responsible for the bloodbath and tragedy which followed in its wake. However, any inequality of power soon disappears when the pleasantries addressed to both the politicians soon give way to anguish and raw anger. She addresses the two by saying, “I hope that before this occasion you would never have received a letter from a courtesan. I also hope that you would never even have set your eyes on me and other women of my type. I also know that my writing a letter is forbidden to yourselves and, that too, such an open letter.”

Chander tailors the courtesan’s plea to the plight of two girls — Hindu and Muslim — from Rawalpindi and Jullundur (Jalandhar), respectively, whose fate will be dependent on the actions of Nehru and Jinnah. The subject of prostitution has been dealt with in Urdu fiction since Mirza Ruswa’s Umrao Jan Ada, and Abdul Ghaffar’s Laila ke Khutoot, and made into an art form by Manto’s various stories. Chander, however, departs from the mainstream by depicting his heroine as having political agency. The story can also be seen as a parable on the contemporary plight of women in both Pakistan and India. This un-named courtesan is easily the most powerful female character in the collection under review. The final paragraph from the courtesan’s address to Jinnah and Nehru reads as follows:

“I have said quite a lot, being swept away by the river of emotion, perhaps I should not have said all this. Maybe this is akin to debasing you. Perhaps no one has yet told or narrated to you more disagreeable things than these. Perhaps you cannot do all of this, not even a little bit, despite that we are free, in India and Pakistan. Perhaps it is even a courtesan’s right to at least ask her leaders what will become of Bela and Batool now?

“Bela and Batool are two girls, two nations, two civilisations, two temples and mosques. Nowadays they live with a prostitute on Faris Road, who conducts her business in a corner near the Chinese barber’s shop. Bela and Batool dislike this business. I have bought them. If I want, I can make them work for me, but I am thinking, I will not do what Rawalpindi and Jullundur did to them. So far, I have kept them apart from the world of Faris Road. But still, when my clients begin washing up in the back room, Bela and Batool’s looks tell me something, something which I cannot bear. I can’t even convey their message to you properly, why don’t you yourselves read it? Pandit Ji, I want that you adopt Batool as your daughter. Jinnah sahib, I want that you think of Bela as your daughter. Just for once, keep them in your home away from the grasp of Faris Road and listen to the dirges of thousands of those souls, which are booming from Noakhali to Rawalpindi and from Bharatpur to Bombay. Can’t it be heard in Government House alone, will you listen to this voice?

Yours sincerely,

A courtesan of Faris Road .”

The story titled ‘Jackson,’ shows the plight of an arrogant Anglo-Indian Deputy Superintendent of Police, the eponymous Jackson who is just four days away from the end of his ‘empire,’ as a result of Partition. Chander has subtly displayed the eventual crumbling away of the world of Anglo-Indian authority. Jackson had already made plans to retire comfortably to England after the end of his “mandate,” divorce his Anglo-Indian wife and live like an English lord by marrying a “real” English countess. His daughters were “reserved for England” and shared his antipathy for their Anglo-Indian blood and fellow Indians. DSP Jackson also duly makes his contribution to colonial India by playing the politics of divide and rule, by arming the leaders of both the Hindu and Muslim communities.

The real master-stroke in the story arrives unbeknownst to Jackson within his own house, when his favourite daughter, Rosie, writes him a letter disowning whatever she had been led to believe about the purity of the Anglo-Indian world and decides to elope with her Anglo-Indian boyfriend, Anand. The come-uppance is too much for Jackson, who consequently commits suicide.

The story is also a prescient and valuable comment on the psychology and mentality of the Anglo-Indian, often seen as a fifth columnist, who partly paved the way for British imperial consolidation in the Indian subcontinent.

The two stories ‘Amritsar: Pre-Independence’ and ‘Amritsar: Post-Independence’ depict the political and social situation in an insurgent city situated in the heart of Punjab, after the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919 and Parition, respectively. The former story is the shortest in the collection and serves to challenge what is taught as official history in Pakistan, about the united, peaceful struggle and sacrifice of Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs against the might of the British Empire. The heroes of the story are the valiant women of Amritsar — Begum, Zainab, Paro and Sham Kaur, who take on the senseless clause of the infamous Rowlatt Act (enforced in the wake of the 1919 massacre), that everyone will have to salute the Union Jack and crawl on their knees to pass from one street to another. All four paid with their lives while resisting. This is a valuable, albeit lesser known, social history of the Amritsar massacre.

The story about post-independence Amritsar is a direct polar opposite to the heart-warming stories of sacrifice across the communal, class and gender divides in the previous story. It focuses on the communal passions that were unleashed in all their fury in 1947, less than 30 years after the same city had shown itself to be above such prejudice.

The two stories offer a chastening history lesson of the kind usually not found in our history books. In the private school where I teach, prescribing both these stories in the ‘O’ Levels curriculum proved to be an eye-opener for my students, and a welcome counterfoil to ‘official’ history.

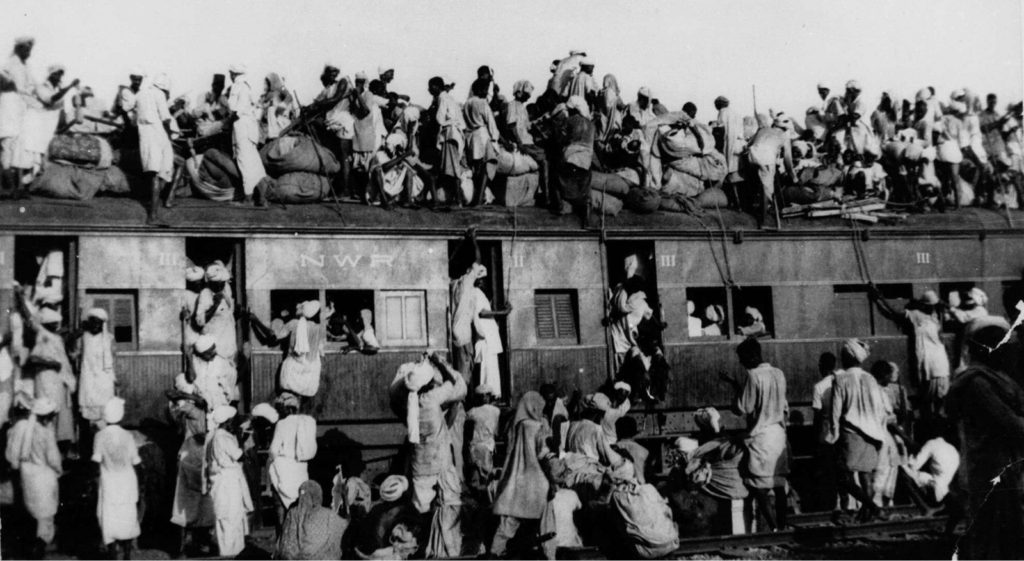

The final story in the collection, ‘Peshawar Express,’ is not only the most notorious but also one of the most frequently anthologised stories about Partition. The story is told from the point of view of a train travelling from Peshawar to Bombay. On its long journey, the express train — usually a symbol of modernity in progressive literature — narrates scenes of recurring bloodbaths of Hindu, Muslim and Sikh refugees fleeing the violence. Chander has shown the number of Muslim casualties to be exactly the same as the number of Hindu or Sikh casualties. This technique has mostly been lamented by right-wing critics on both sides of the divide. While critics are free to dislike any work of art or literature that they wish, it would be unfair to consign the entire volume to the dustbin. Especially when Chander has explained why he chose his fictional vigilantes to ‘balance’ the casualties in this way: “So that the balance of population should be maintained between India and Pakistan.” I have not seen any critic of Chander address this controversial line in the story. Therefore, I suspect that the criticism is directed more against the progressive, socialist philosophy espoused by Chander, rather than the way he has depicted the atrocities of Partition. Hailing from a family in Wazirabad in Punjab and raised and educated in Lahore, Chander can hardly contain his anger when Taxila, Sirkap and Wazirabad — the ancient centres of peace, learning, arts and crafts — are re-christened with blood in 1947. He voices his feelings through the ‘Peshawar Express:’ “A thousand curses on these leaders, on their next seven generations, who destroyed this beautiful Punjab… and eclipsed its pure soul and filled its strong body with the pus of hatred…”

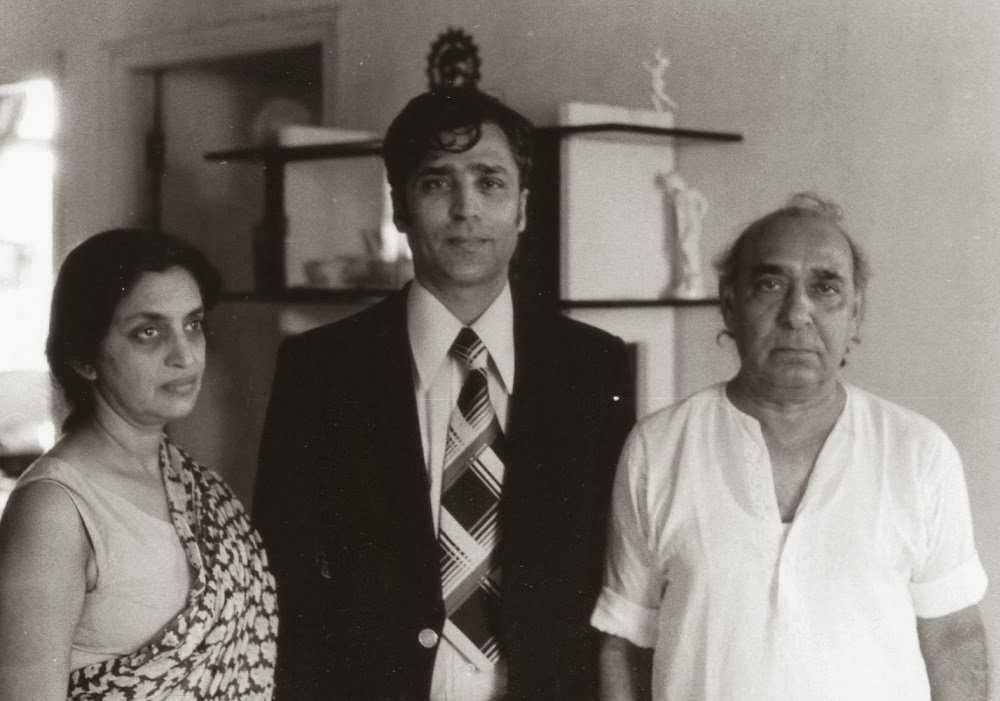

Krishan Chander (far right) with his wife Salma Siddiqui.

For me, the most telling incident in the story comes towards the end, where a beautiful and intelligent young woman, having endured the murder of her parents and younger siblings by a mob, asks the ruffians to consider marrying and thus sparing her life. She is brutally murdered, and with her the lessons of the book she was carrying, The Theory and Practice of Socialism by John Strachey; a productive life snuffed out prematurely.

Reading Chander’s stories on the 70th anniversary of Partition, one gets the feeling that the women were affected much more adversely than the men, in what has variously been described as a ‘holocaust’ and ‘genocide’ of 1947. Yet it is the women who are the saving grace of a humanity, which will be born anew, however dark and hopeless the situation. The heroines are there in most of the stories, rebelling against their plight and almost countering the brutalities of men such as Kamlakar and Jackson. Amongst these, are the un-named courtesan, the Anglo-Indian Rosie who breaks away from the artificial world created for her by her authoritarian father, the four doughty daughters of Amritsar drowned in the blood of martyrdom and the unfortunate socialist who bore the assassin’s knife with scholarly grace.

Chander writes as if to refute the guilty charge of humans as savages in the dock, when he says, “We are humans. We are the standard-bearers of creation in this whole universe, and nobody can kill creation. Nobody can rape or dishonour it. Because we are creation and you are destruction; you are savages, you are beasts, you will die; but we will not, because humans never die. They are not beasts, the soul of kindness, the outcome of divinity, the pride of the universe.”

All the translations from Urdu are by the writer.

The writer is a social scientist, translator, book critic and a prize-winning dramatic reader based in Lahore.