70, and Looking Even Better

By Maliha Rehman | Special Report | Published 7 years ago

Fashion in Pakistan may have mushroomed into an all-encompassing, glittering behemoth but there was a time when it simply simmered within the country’s cultural fabric. Overshadowed by perpetual political crossfire and mayhem, it was the nascent creative force that often went unnoticed but remained indelible.

It persisted: in the ethnic-wear that couturier Sughra Kazmi created for miniature dolls, which then began to be customised for women; in the kaftans that were exported by textile heavyweights like Artistic Milliners which would also be made available in limited numbers locally; in the ‘awami’ outfits popularised by political trailblazers, the bohemia emulated by pop icons and the fanfare that hit markets with the arrival of designer lawn. Gathering strength, treading carefully in a political and cultural minefield and eventually gaining momentum, fashion eventually came to the forefront.

“The world at large may not always be aware of it but Pakistan has always actually been a very fashionable country,” observes veteran designer Maheen Khan, who has witnessed the ebb and flow of the industry over time. “We’ve always been very particular about what we wear and all through history, the country’s sartorial identity has been defined by some very fashionable people.”

Sifting through the annals of history, here are some local fashion statements that became all the rage. Many of them have come back in vogue time after time — and many have now become fashion staples:

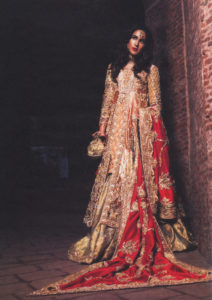

The gharara — then and now

The decade that marked the birth of Pakistan was often captured in images where female

The decade that marked the birth of Pakistan was often captured in images where female  figures stood tall with their male counterparts, choosing a wardrobe that resonated with the times and set trends in motion. The country’s first lady, Begum Ra’ana Liaquat Ali Khan, wife of the first prime minister, had a penchant for the traditional gharara. The farshi gharara, later relegated to wedding-wear, was employed as dailywear within her wardrobe, worn gracefully at political conventions and while delivering speeches. Fatima Jinnah, sister of the country’s founder, also often opted for the cotton gharara, sometimes in a plain crisp white, or at other times embellished with delicate threadwork.

figures stood tall with their male counterparts, choosing a wardrobe that resonated with the times and set trends in motion. The country’s first lady, Begum Ra’ana Liaquat Ali Khan, wife of the first prime minister, had a penchant for the traditional gharara. The farshi gharara, later relegated to wedding-wear, was employed as dailywear within her wardrobe, worn gracefully at political conventions and while delivering speeches. Fatima Jinnah, sister of the country’s founder, also often opted for the cotton gharara, sometimes in a plain crisp white, or at other times embellished with delicate threadwork.

In later years, the farshi gharara ceased to be worn as daywear, overtaken by the easier to wear shalwar kameez. Variations of it, though, continued to venture into fashion: the baggy Dhaka pajama and the currently popular simmered gharara pant, for instance. Coming full circle, one now observes the cotton gharara making a comeback this summer, particularly popularised by designer Zara Shahjahan and high street brands like Generation.

The changing face of the shalwar

The shalwar flatters the Pakistani woman’s physique, which is probably why it remains a wardrobe staple that has never completely faded out from wardrobes. Over time, though, one has seen it evolve into myriad silhouettes. In the ‘50s and ‘60s, women paired tight ‘teddy’ shirts with either a baggy shalwar with a wide paincha or in complete contrast, a very fitted version. The heavily gathered Patiala has constantly flitted back and forth into the sartorial landscape, frequently being replaced by the much more flattering and wearable half-Patiala. The ’70s saw the genie shalwar, or Harem, become trendy. Other versions include the ‘dhoti’; the ‘double dhoti’; the wide ‘mullah’ shalwar, which ends above the ankles; the ‘tulip’ with its pointy tips and the ‘cowl’ shalwar.

The shalwar flatters the Pakistani woman’s physique, which is probably why it remains a wardrobe staple that has never completely faded out from wardrobes. Over time, though, one has seen it evolve into myriad silhouettes. In the ‘50s and ‘60s, women paired tight ‘teddy’ shirts with either a baggy shalwar with a wide paincha or in complete contrast, a very fitted version. The heavily gathered Patiala has constantly flitted back and forth into the sartorial landscape, frequently being replaced by the much more flattering and wearable half-Patiala. The ’70s saw the genie shalwar, or Harem, become trendy. Other versions include the ‘dhoti’; the ‘double dhoti’; the wide ‘mullah’ shalwar, which ends above the ankles; the ‘tulip’ with its pointy tips and the ‘cowl’ shalwar.

In more recent times, Feeha Jamshed created the shalwar jumpsuit where a shirt on the upper torso extended to a pleated shalwar on the lower half. Maheen Khan’s Gulabo perpetually delves into shalwar hybrids, including the shalwar pant that can be buttoned up to be a shalwar and opened to become a straight pant. At Generation, shalwars have lately dabbled with tassels, draw-strings at the waist and cuffs at the ankles. And so the shalwar continues its journey — breathable, wearable and always very, very interesting.

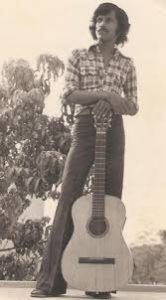

Bell-bottoms and

The Beatles

Every now and then, the bell-bottom has nudged itself into fashion. Flower power was the mantra defining the

Every now and then, the bell-bottom has nudged itself into fashion. Flower power was the mantra defining the swinging ’60s, epitomised by bands like The Beatles and then carried onto the ’70s by music sensations like Abba and The Carpenters. Their wardrobe invariably featured printed floral shirts worn with bell-bottoms that were fitted at the waist and flared to baggy ‘bells’ at the lower leg. Perhaps one of the most memorable bell-bottom enthusiasts was Cher, who wore them with straight long hair and an oversized pair of sunglasses. The trend easily trickled down to the Indo-Pak subcontinent.

swinging ’60s, epitomised by bands like The Beatles and then carried onto the ’70s by music sensations like Abba and The Carpenters. Their wardrobe invariably featured printed floral shirts worn with bell-bottoms that were fitted at the waist and flared to baggy ‘bells’ at the lower leg. Perhaps one of the most memorable bell-bottom enthusiasts was Cher, who wore them with straight long hair and an oversized pair of sunglasses. The trend easily trickled down to the Indo-Pak subcontinent.

Popular heroes and heroines like Amitabh Bachchan, Rishi Kapoor, Neetu Singh and a ‘hippie’ Zeenat Aman popularised the trend. In Pakistan, Alamgir and Mohammad Ali Shehki, pop icons of the ’70s and ’80s, opted for the bell-bottom, as did cinema actors like Nadeem and Waheed Murad.

Fast-forwarding to present day, the bell-bottom, continues to be an option, seen on the catwalk every now and then — embroidered at the lower leg or with funky prints — channelling nostalgia and a boho vibe. It’s also visible in lawn catalogues, testifying to its wearability, suitable for the daytime lunch as well as for the evening soiree.

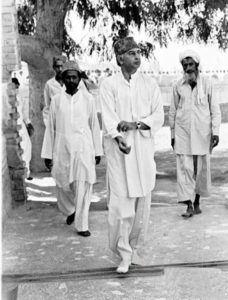

‘Awami’ androgyny

In the ’70s, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto sought to become one with the country’s labourers by donning the ‘awami’ jora and, unknowingly, set off a nationwide inclination towards androgyny. The ‘awami’ shirt was consciously designed to be the same as the uniform worn by the lower economic classes at the time: high-collared with two pockets, a round hem and paired with a shalwar. Once Bhutto glamourised it, the country’s crème de la crème followed suit, opting for it especially in the day time.

In the ’70s, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto sought to become one with the country’s labourers by donning the ‘awami’ jora and, unknowingly, set off a nationwide inclination towards androgyny. The ‘awami’ shirt was consciously designed to be the same as the uniform worn by the lower economic classes at the time: high-collared with two pockets, a round hem and paired with a shalwar. Once Bhutto glamourised it, the country’s crème de la crème followed suit, opting for it especially in the day time.

Funky bohemia for the shalwar kameez

The ’70s also marked the rise of Teejays. Tanveer Jamshed pioneered the high street, injecting it with funky psychedelia and fashion never completely changed back again. “Teejays is to shalwar kameez what Levi’s is to denim,” he infamously said, proceeding to tweak the outfit so that it ceased to be merely comfortable daywear and became a fashion statement. At Teejays, shirts were pocketed and clasped shut with quirky buttons; sleeves were squared; colour blocks ran in zig-zags and polka dots were splattered in multi-coloured clusters.

The ’70s also marked the rise of Teejays. Tanveer Jamshed pioneered the high street, injecting it with funky psychedelia and fashion never completely changed back again. “Teejays is to shalwar kameez what Levi’s is to denim,” he infamously said, proceeding to tweak the outfit so that it ceased to be merely comfortable daywear and became a fashion statement. At Teejays, shirts were pocketed and clasped shut with quirky buttons; sleeves were squared; colour blocks ran in zig-zags and polka dots were splattered in multi-coloured clusters.

Popularised by TV dramas where iconic actresses like Shehnaz Sheikh and Marina Khan wore the clothes, the ‘Teejays’ revolution was a landmark in local fashion. It paved the way for the present-day motley crew of designers, providing a business model towards which they could aspire. It also set the precedent for the funky, fun shalwar kameez the ‘Teejays’ way.

The lawn revolution

Unstitched designer lawn arrived in Pakistan, conquered, and is yet to relinquish its throne. The very first limited edition lawn collections can be traced back to the ’60 s and ’70s, initiated by mills such as the Mohammad Farooq Textile Mills in Karachi and Kohinoor Textile Mills in Lahore. It was much later, in the ’90s, that mills began to collaborate with well-known fashion designers. Rizwan Beyg pioneered the business in the early ’90s; his very first collaboration was with Crescent Textiles, while later in his career he went on to work with Five-Star Textile Industries, Sitara Textile and Al-Zohaib Textiles. Two months after Rizwan, Shamaeel Ansari stepped into the business. She, too, joined hands with Crescent Textiles, and later launched one of the country’s very first flagship stores ‘Filigree By Shamaeel’ where exclusive prints were retailed. The Shamaeel-Crescent partnership also introduced industrial embroideries on yards of fabric that ranged from luxe silks and organzas to cotton.

Unstitched designer lawn arrived in Pakistan, conquered, and is yet to relinquish its throne. The very first limited edition lawn collections can be traced back to the ’60 s and ’70s, initiated by mills such as the Mohammad Farooq Textile Mills in Karachi and Kohinoor Textile Mills in Lahore. It was much later, in the ’90s, that mills began to collaborate with well-known fashion designers. Rizwan Beyg pioneered the business in the early ’90s; his very first collaboration was with Crescent Textiles, while later in his career he went on to work with Five-Star Textile Industries, Sitara Textile and Al-Zohaib Textiles. Two months after Rizwan, Shamaeel Ansari stepped into the business. She, too, joined hands with Crescent Textiles, and later launched one of the country’s very first flagship stores ‘Filigree By Shamaeel’ where exclusive prints were retailed. The Shamaeel-Crescent partnership also introduced industrial embroideries on yards of fabric that ranged from luxe silks and organzas to cotton.

However, it is designers Sana Safinaz, who are associated most frequently with the mass lawn frenzy. Over the course of their careers in lawn, their collections of unstitched fabric would infamously cause traffic jams and even fistfights. It was in the late ’90s that the designer duo began designing lawn for Al-Karam Textile Mills, going on to work with Lakhany Silk Mills before launching their own independent lines.

Designer-created lawn has often been defined as the ‘desi’ high-street fashion, with high-end aesthetics translated to economically priced  fabric for the masses. Moving away from formulaic florals, one also noticed prints inspired by architecture, the Mughal dynasty, the French Renaissance and city skylines. Moving beyond mere prints, entire ensembles are brought together much like jigsaw puzzles: embroideries, trimmings in silk and organza and dupattas created with fine chiffons and silks.

fabric for the masses. Moving away from formulaic florals, one also noticed prints inspired by architecture, the Mughal dynasty, the French Renaissance and city skylines. Moving beyond mere prints, entire ensembles are brought together much like jigsaw puzzles: embroideries, trimmings in silk and organza and dupattas created with fine chiffons and silks.

Cashing in on the potential of the designer lawn market, mill and designer collaborations continue while quite a few designers have also chosen to finance their own collections: Faraz Manan for Crescent, Khadijah Shah with Elan Lawn, Zara Shahjahan with her eponymous collection, Maria B. Lawn, Saira Shakira for Crimson Lawn, Farah Talib Aziz for Lakhany Silk Mills, among many others.

Unfortunately, today’s profusion of designer lawn is hardly as trendy as its predecessors from the ’90s, leaning too often towards generic patterns. And yet, lawn continues to be the country’s fabric du jour for the sheer convenience and occasional spurts of fashion that it offers.

From Truck to High Street

Vivacious, cheeky truck art is unique to Pakistan: the glittering chamak-patti, intertwining filigree in multi-colours, kohl-lined eyes peering into the distance and coquettish peacocks flitting down the lengths of trucks. Latching onto the truck-art trend, local designers created a sensation. It was in 2013 that Rizwan Beyg’s truck-art collection was showcased at the PFDC Sunsilk Fashion Week with truck-art patterns worked onto jackets, boots, bags and jeans. Maheen Khan’s Gulabo brought the kaleidoscopia down to the high-street, transferring the patterns onto printed shirts, bags and kitschy scarves splattered with slogans. And in 2012, photographer Tapu Javeri dabbled in designing a range of ‘Tapulicious’ bags where a ‘chakra’ of famous faces, architectural monuments and truck-art were fused together.

Vivacious, cheeky truck art is unique to Pakistan: the glittering chamak-patti, intertwining filigree in multi-colours, kohl-lined eyes peering into the distance and coquettish peacocks flitting down the lengths of trucks. Latching onto the truck-art trend, local designers created a sensation. It was in 2013 that Rizwan Beyg’s truck-art collection was showcased at the PFDC Sunsilk Fashion Week with truck-art patterns worked onto jackets, boots, bags and jeans. Maheen Khan’s Gulabo brought the kaleidoscopia down to the high-street, transferring the patterns onto printed shirts, bags and kitschy scarves splattered with slogans. And in 2012, photographer Tapu Javeri dabbled in designing a range of ‘Tapulicious’ bags where a ‘chakra’ of famous faces, architectural monuments and truck-art were fused together.

Several years later, truck art continues to surface on the local high street. It may no longer be a distinctive concept but it always catches the eye — multicoloured, tongue-in-cheek, intrinsically Pakistani.

Trend and Tradition

With a rich cultural heritage in its genealogy, local fashion has always been rich in ethnic inspirations that

With a rich cultural heritage in its genealogy, local fashion has always been rich in ethnic inspirations that  remain timeless in their beauty. In any renowned atelier across the country, weavers and embroiderers peer onto screens as they create images with minute threadwork, minakari and indigenous weaves. For instance, within Bunto Kazmi’s atelier, delicate embroideries replicate paintings; handworked kamdani, dabka, French knots and resham are worked together to recreate flora, fauna, hunting scenes, glimpses from the Mughal dynasty and stories from Persian literature. In the studios of other veteran designers like Rizwan Beyg, Faiza Samee and Nilofer Shahid, the love for craft reigns supreme: shirts are worked with delicate chikankari, edged with golden gota, embellished with intricate marori or set apart by Kashmiri phulkari or painstakingly cross-stitched flowers.

remain timeless in their beauty. In any renowned atelier across the country, weavers and embroiderers peer onto screens as they create images with minute threadwork, minakari and indigenous weaves. For instance, within Bunto Kazmi’s atelier, delicate embroideries replicate paintings; handworked kamdani, dabka, French knots and resham are worked together to recreate flora, fauna, hunting scenes, glimpses from the Mughal dynasty and stories from Persian literature. In the studios of other veteran designers like Rizwan Beyg, Faiza Samee and Nilofer Shahid, the love for craft reigns supreme: shirts are worked with delicate chikankari, edged with golden gota, embellished with intricate marori or set apart by Kashmiri phulkari or painstakingly cross-stitched flowers.

Many among the younger generation of designers have followed suit: the House of Kamiar Rokni has spun gota and rilli to all-new patterns. Khadijah Shah works intricate embroideries with sequins; Nida Azwer is passionate about hand-embroidered shawls; Zaheer Abbas has fashioned entire collections with indigenous ajrak; Adnan Pardesy dexterously creates origami patterns from gota; Naushaba Brohi works with craftswomen in interior Sindh bringing together dori, beads, rilli and embroidery to create modern silhouettes and statement jewellery. Within retail, veteran Noorjehan Bilgrami stands out for staying true to her love for hand-woven khaadi. Following in her footsteps, high street heavyweight Khaadi is soon launching a retail line dedicated entirely to hand-woven apparel and accessories, titled ‘Chapter 2.’